Noncompetes are bad for workers—let's get rid of them

Noncompetes forced three nurses to quit their jobs during the pandemic.

On October 8, 2020, three Wyoming nurses got a nasty shock: A judge ordered them to stop providing home health care to patients in the southwest corner of the state, where all three worked. Their previous employer, Best Home Health and Hospice, said the women had signed noncompete agreements. After they switched jobs, Best Home sued to enforce the contracts.

One of the nurses, Jennifer Brown, told me she had to commute more than two hours to find a job outside the noncompete zone. She had sole custody of her granddaughter, who was then just 1 year old. Brown struggled to find child care with hours long enough to accommodate the 12-hour workday created by her long commute. The new job also came with a big pay cut, from $36 per hour to $21.

“I burned through all my savings, and I got to the point where I had a roommate to pay the bills,” Brown, who is 47, told me in a phone interview. After about three months, she reluctantly moved to Pennsylvania, where she had family to help with child care. She has since moved to Michigan to work as an operating room nurse.

“Not only did they take away my means to support myself—they took away my means to feed my granddaughter,” Brown told me. “As a nurse, I should never have that problem.”

Another woman, Carol Wolfe, became a traveling nurse in North Carolina, according to her attorney, Clark Stith. ”Being a traveling nurse is hard,” Stith told me. Wolfe had been working as a nurse for “30-some years,” Stith said. “You're getting toward retirement, then suddenly you're living out of a motel, traveling around wherever you can find work.”

Stith agreed to represent all three women in a case that went all the way up to the Wyoming Supreme Court. In July, the state’s highest court reversed the injunction.

But the three nurses are still trying to recover lost wages from Best Home after their court win. And Brown says it will be “almost impossible” for her to catch up from the financial losses of the past year. She describes it as one of the most stressful periods of her life.

Best Home didn’t respond to multiple emails seeking comment about the case.

Stith isn’t just an attorney—he’s also a Republican state representative in Wyoming. And he recently proposed legislation that would ban the enforcement of noncompete agreements in the state. He took his inspiration from California, where courts have refused to enforce almost all noncompete agreements for more than a century. Laws like this have recently been gaining momentum in other states. Earlier this year, the District of Columbia enacted a sweeping ban on noncompete agreements, which will go into effect in April.

Other states have passed more targeted legislation prohibiting the use of noncompete agreements against low-wage workers. In my view, California and D.C. have taken the right approach with near-total bans on noncompete enforcement. Every state, if not the federal government, should follow suit. But the case against noncompete rules is particularly strong when it comes to workers on the lower rungs of the economic ladder.

Low-wage noncompetes are surprisingly common

A decade ago, discussions of noncompete agreements tended to focus on corporate executives, engineers, and others who have access to sensitive technical or strategic information. The case for enforcing noncompete laws is strongest for these types of workers.

But in recent years, we’ve learned that noncompete deals are being used up and down the income spectrum. There have been numerous stories about noncompetes being used against workers with below-average wages:

In 2014, the Huffington Post reported that Jimmy John’s was requiring its hourly sandwich makers to sign noncompete agreements. (The sandwich chain eventually agreed not to enforce the agreements after a public backlash.)

In 2015, the Verge revealed that Amazon was making low-paid warehouse workers sign noncompetes. (The company quickly stopped doing that.)

In 2016, PBS covered a legal battle in which a lampshade maker sued a worker making $9 an hour for switching to a rival.

In 2019, the Wall Street Journal wrote about companies that ask interns to sign noncompete agreements.

However galling they are, anecdotes like this don’t tell us how widespread these practices really are. But a new analysis from the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis provides a systematic look at this question.

The researchers looked at data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, a government survey that follows a sample of adults over the course of their lives. Every few years, the government asks the same men and women a series of questions about their lives and careers.

In the most recent round of interviews, conducted in 2017 and 2018, researchers added a new question for the cohort then in their mid-30s: whether they had signed a noncompete agreement in their current or most recent job. Overall, 15 percent of workers said they were subject to noncompete agreements.

This is roughly consistent with earlier research; a 2014 online survey found 18 percent of workers said they were bound by noncompete agreements.

Evan Starr, the lead author of that 2014 survey, believes the new results are significant. “This is the first government-collected data on noncompete agreements,” he told me recently. The fact that it's a large, random, government-sponsored survey gives it extra credibility.

That topline 15 percent figure likely understates how widely noncompete clauses are used in the labor market. Employees don’t always read their contracts carefully or remember what they’ve signed. In a 2019 survey of businesses, more than 30 percent said they required all of their employees to sign noncompete agreements.

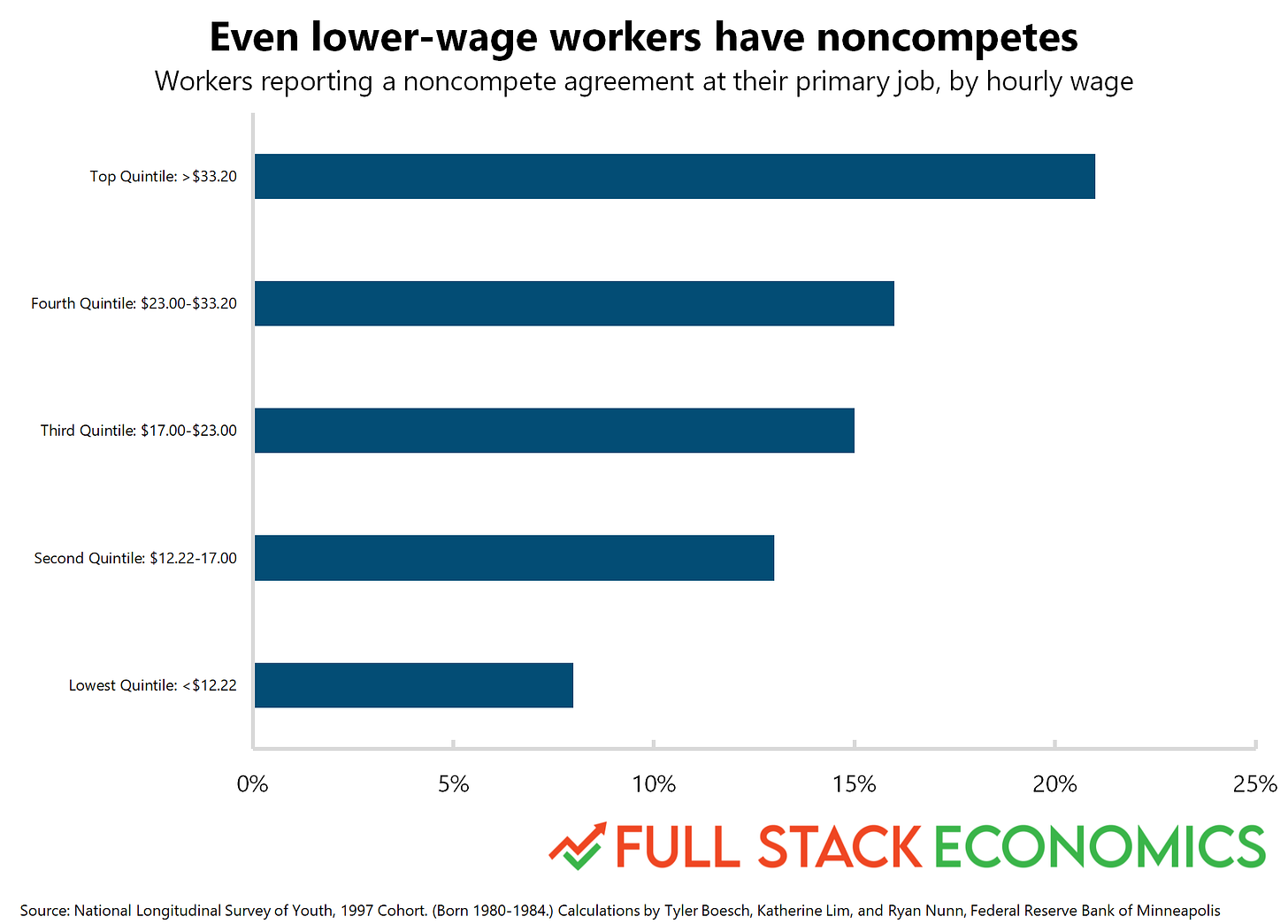

As you might expect, higher-paid workers are more likely to be subject to noncompete clauses. The Minneapolis Fed calculated that 21 percent of workers in the top income quintile sign such agreements. But even in the bottom quintile—which tops out at about $12 per hour—8 percent of workers said they’d been asked to sign such agreements.

Non-enforcement works well in California

Why enforce noncompetes at all? Advocates argue that refusing to enforce noncompete agreements could discourage companies from investing in their workers and in new technologies. Companies worry that employees could take valuable strategic or technical information with them when they go to work for a competitor.

Patents and trade-secret laws are supposed to prevent this kind of intellectual theft, but executives and engineers frequently have valuable knowledge in their heads that isn’t covered by patent or trade-secret laws. If this kind of theft happened too frequently, companies might underinvest in new technologies—or they might flee states that fail to enforce noncompete contracts.

This plausible theory has a massive practical problem: California. As I mentioned before, California courts have refused to enforce noncompete agreements for more than a century. And California has not exactly been a laggard when it comes to innovation. California-based tech giants like Apple and Google spend massive sums on research and development and do not seem eager to relocate.

Indeed, there’s a famous argument that California’s refusal to enforce noncompete agreements actually promoted its technology sector. In a 2017 piece for Vox, I examined the rise of Silicon Valley in the 1980s:

Why did Silicon Valley boom while Boston’s technology sector fizzled out? In an influential 1994 book, political scientist AnnaLee Saxenian argued that the difference was cultural. In Boston-area technology companies, engineers expected to work for one company for life. In the San Francisco Bay Area, by contrast, it was common for workers to hop from one company to another—and even to found new startups that competed with their old employers.

The fact that California courts don’t enforce noncompete agreements was a key reason this culture existed. And while this kind of job-hopping is frustrating for employers who lose workers, Saxenian argued that it made Silicon Valley, as a whole, stronger. When someone invented a good idea in one company, it would quickly diffuse across Silicon Valley, improving the performance of other companies nearby. This freewheeling culture seems to have produced a faster pace of innovation than what you got in areas where lifetime employment was the norm.

In other words, Silicon Valley’s success suggests the standard case for enforcing noncompete agreements might be not just wrong but backward. Letting companies tie up their best workers actually slows the pace of progress.

Don’t enforce non-competes against low-wage workers

Regardless of which side you take in that debate, enforcing noncompetes makes no sense in low-tech industries and against workers down the income scale. Your average home health care company isn’t developing cutting-edge technologies. Letting health care providers lock up nurses with noncompete contracts doesn’t have any broader social benefits—it just gives them more power over their workers. It’s harder to ask your boss for a raise if your boss knows you’re not allowed to work for other nearby employers.

A study published last year looked at the results of a 2007 Oregon law that banned the enforcement of noncompete agreements against lower-paid and hourly workers. The economists Michael Lipsitz and Evan Starr crunched the numbers and estimated that the law raised the wages of hourly workers by 2 to 3 percent.

That figure is particularly impressive because it’s an average across all hourly workers—and only a small fraction of those workers were subject to noncompete agreements. This suggests that the wage impact on affected workers could be much higher—as high as 14 to 21 percent.

“Low-wage workers are unlikely to have legal help when encountering a noncompete,” said Ryan Nunn, one of the authors of the Minneapolis Fed study, in a phone interview. “They are poorly informed about what the noncompete means for them and how it could be enforced against them.”

Non-compete reform is gaining momentum

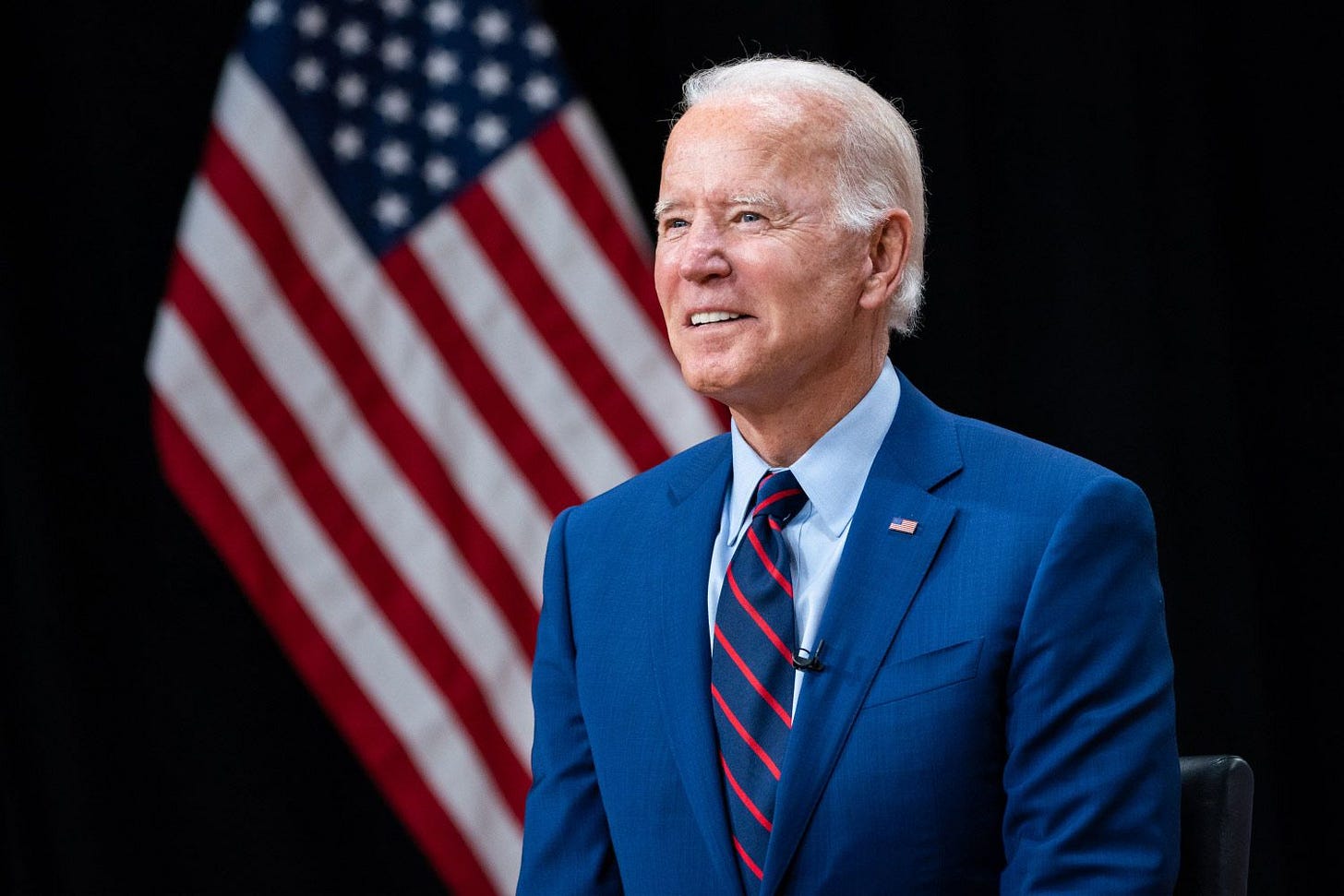

In July, President Joe Biden signed an executive order asking the Federal Trade Commission (an independent agency) to limit or ban the enforcement of noncompete agreements. Days later, the Uniform Law Commission approved a model statute that restricts enforcement of noncompete agreements—including banning their enforcement against low-wage workers. The ULC doesn’t have the power to change laws in any specific state, but state legislatures often use ULC standards as a starting point for drafting their own laws.

Even before this change, a number of states had been passing laws to restrict enforcement of noncompetes. In 2016, Illinois followed Oregon’s lead, passing legislation banning enforcement of noncompetes against low-wage workers. Earlier this year, the state expanded this to cover workers making less than $75,000. Massachusetts banned enforcement of noncompetes against hourly workers in 2018.

While the case against enforcing noncompetes is strongest for low-wage workers, I think it makes sense to ban enforcement across the board. The example of California suggests that these agreements are not necessary for a thriving economy and are probably counterproductive. Companies have other ways to protect their ideas against outright theft by departing employees—see, for example, Google's trade secrets case against former self-driving engineer Anthony Levandowski.

More fundamentally, choosing where you work is an important freedom. The enforcement of noncompete agreements can impose large financial and emotional costs on individuals, as the story of the Wyoming nurses illustrates. So even if you could demonstrate that Wyoming’s vigorous enforcement of noncompete law modestly improved the performance of the state’s economy, I don’t think that would justify the hardships the law imposes on people like Jennifer Brown, Carol Wolfe, and the people for whom they care. If the effect of a common business practice is that nurses are being kept from their patients in the middle of a pandemic, when there’s an ongoing shortage of health care providers, it’s probably time for that practice to go.

This piece marks the launch of a new partnership with Slate. Going forward, some of our best pieces will be published simultaneously here and at Slate.com. This will help us grow the Full Stack Economics readership.