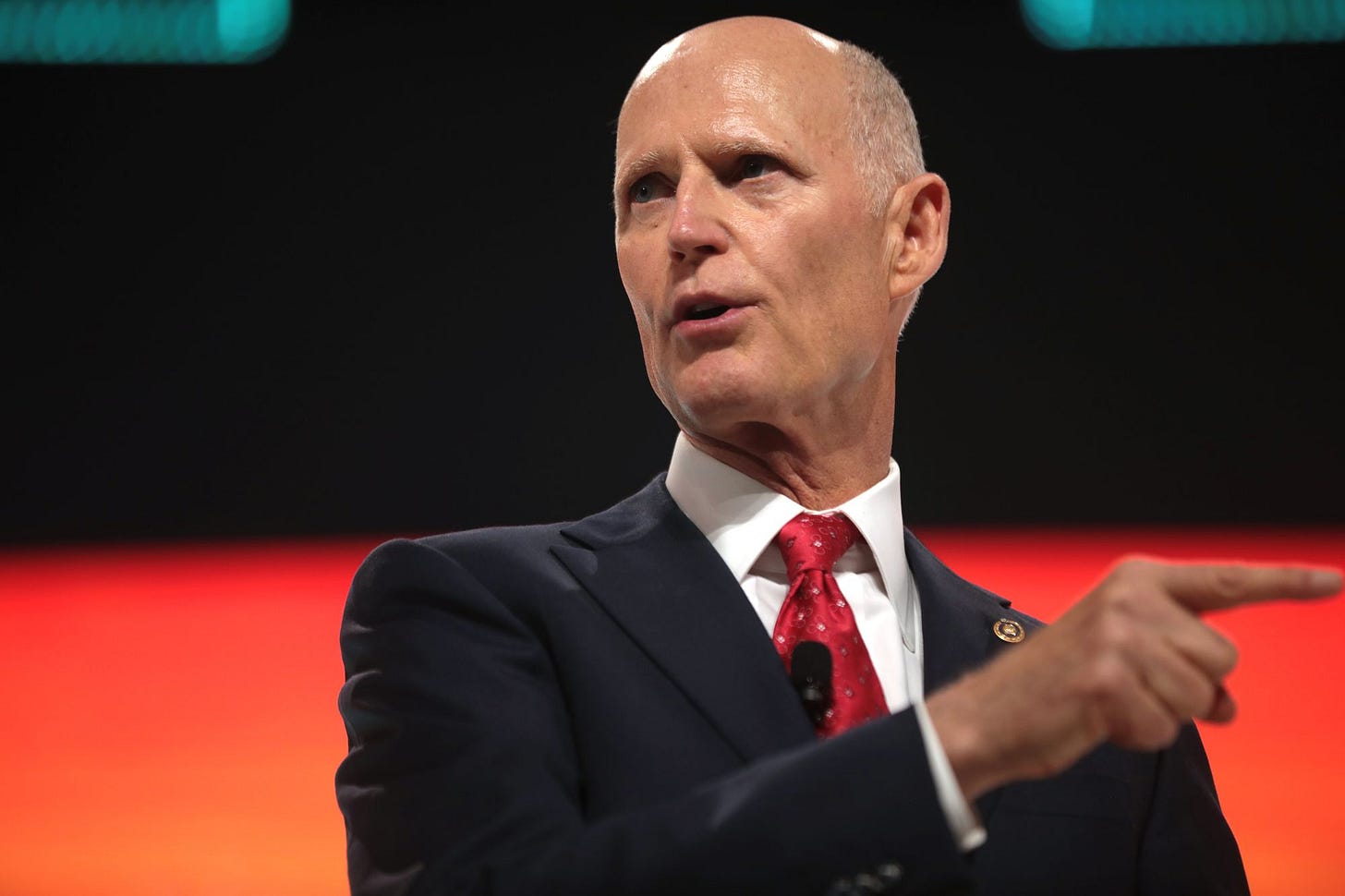

This GOP Senator can’t stop talking about his plan to raise taxes

But his colleagues really wish he would.

Sen. Rick Scott (R-FL) started a political firestorm last month when he released an 11-point “Rescue America” plan. While there is plenty to argue about in this document, the part that most caught the attention of economic policy media was the following: “all Americans should pay some income tax to have skin in the game, even if a small amount. Currently over half of Americans pay no income tax.”

By its own admission, this plan would seem to raise taxes on a lot of people. The exact number is unclear. First, the number of nonpayers is a moving target. It is likely to return to under half of Americans after some pandemic-era policies lapse. Second, in later clarifications, Scott made exceptions for several broad categories of non-taxpayers.

But the scent of a tax hike to attack quickly sent Washington into a bipartisan feeding frenzy. Scott caught criticism from both Democrats, like White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki, and fellow Republicans, like Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY), who slapped the idea down.

“We will not have as part of our agenda a bill that raises taxes on half the American people,” McConnell told reporters. “That will not be part of the Republican Senate majority agenda.”

Nonetheless, Scott defended the idea in a Wall Street Journal op-ed last Thursday.

This dismayed some Republican operatives who were hoping he’d let the issue die. Scott is the chair of the National Republican Senatorial Committee, tasked with winning Senate seats for Republicans. While the Rescue America plan is Scott’s alone, it is billed as his vision for the Republican Party if it takes back Congress in 2022. But Republican strategists are not on board with either the message or, in most cases, the substance. They see shades of prior defeats in Scott’s strategy.

“Everyone chips in” is one of those ideas that sounds nice to some ordinary people who aren’t highly engaged with fiscal policy debates, and there are short-run gains to pleasing such people. But the idea crumbles under the greater scrutiny that would come from operationalizing it, and it will become a liability in the longer run, if not immediately.

The plan is weak on the free market economics

The economics of Scott’s idea are unappealing—even if you come at this from a free-market perspective. The traditional case free-market Republicans make about taxes is twofold.

Point One: Taxes shift spending power from American families to the government. Individuals buying for themselves are disciplined and knowledgeable about what they need. Government officials spending other people’s money are not.

Point Two: High marginal tax rates reduce the market returns to economically productive efforts, like working harder, working more efficiently, or switching jobs to something the market values more. We’re likely to get less of these activities and be worse off.

I sympathize with both of these arguments, and I suspect Scott does too. Which makes it curious that his policy idea fails on Point One: it takes spending power out of private hands.

On Point Two, he fares somewhat better. If you add to the tax burden at a lower level of income, while leaving the tax burdens at higher levels of income unchanged, you actually reduce the marginal tax rates—the extent to which earning new dollars incurs new taxes. You can also perhaps use the money from the minimum tax to cut marginal rates higher up the spectrum. But if you’re a small government politician by nature, you probably should have more free market-friendly ways to pay for your tax cuts.

Ultimately, I don’t think Scott’s view is about economics alone. Free market ideology doesn’t leave much room for raising taxes.

A zombie Republican pop-political science theory

Instead, I think the Scott’s references to “skin in the game” suggest a kind of bank-shot strategy based on dubious right-wing pop-polisci.

“The federal government has figured out how to disconnect many Americans from fiscal reality,” Scott wrote in his WSJ op-ed. “Politicians peddle a fiction that they can waste as much money as they want with no downside.” The cure? “Even if it is just a few bucks, everyone needs to know what it is like to pay some taxes.”

As National Review’s John McCormack notes, Scott's idea assumes that even small income tax sums will create a strong emotional investment in fiscal responsibility. Furthermore, it requires that the other taxes people pay, such as payroll taxes, do not inculcate that same ethos.

It’s a convoluted strategy: raising people’s taxes now in the hopes that they will come around to voting for you later, because of that very same tax hike that you foisted on them. The government really does waste money, and I wish the public cared more! But direct arguments are much more likely to persuade voters of this.

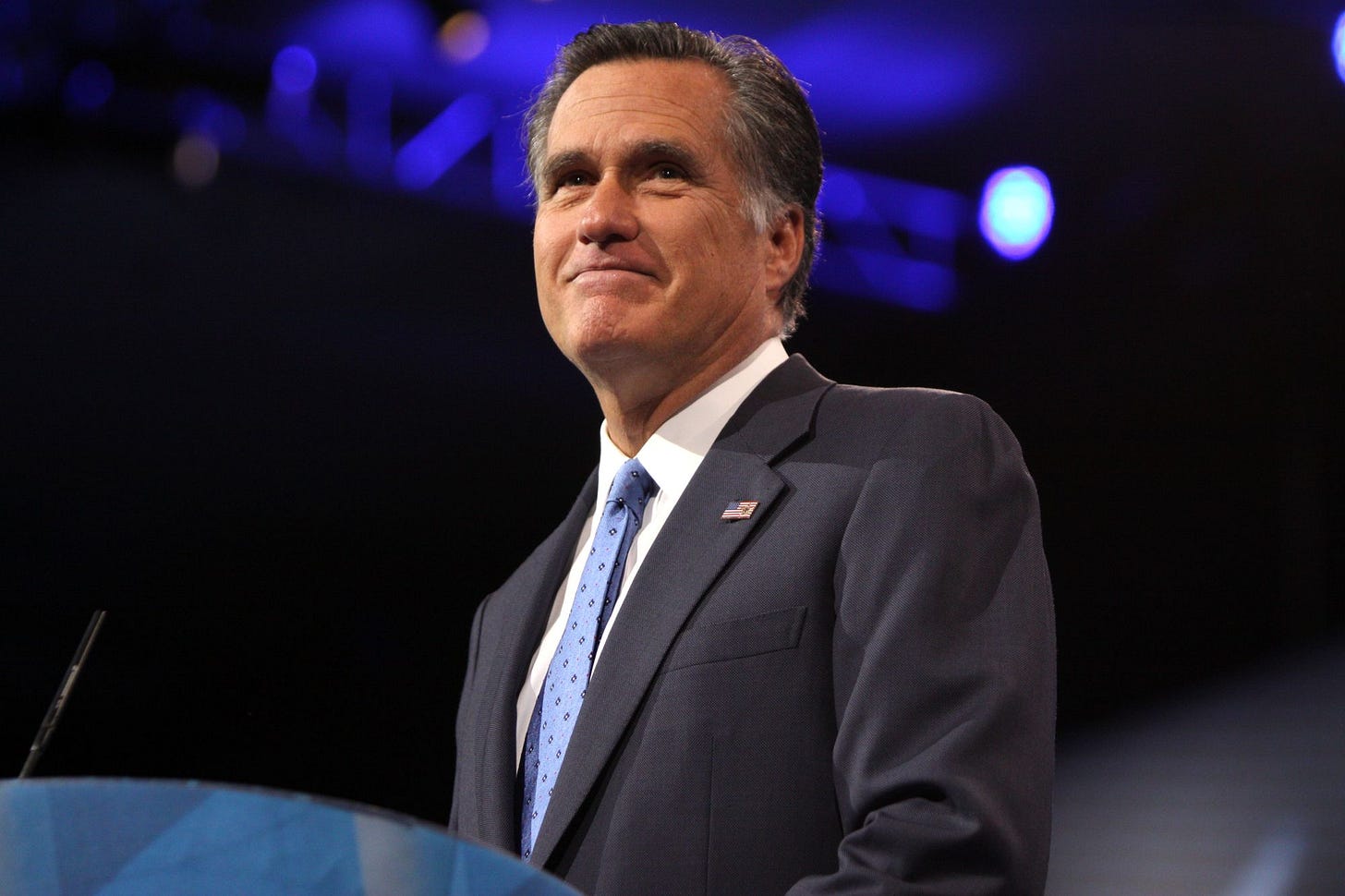

During the 2012 presidential campaign, Mitt Romney, then the Republican nominee, was famously criticized for remarks he made at a private fundraiser, about the 47 percent of Americans who do not pay income taxes, whom he described as “dependent on the government” and who “believe that they are victims.” Romney, who lost the election to Barack Obama, later told journalists he regretted the remarks.

Rick Scott is making much the same mistake. As Josh Barro writes, “on taxes, at least, Scott is pushing the party back into Romney-Ryan-era ‘47%’ territory.” But I think Barro even understates the similarity. It’s not just the way the idea might ruffle feathers. It’s also the same pop-polisci theory. A less-remembered part of Romney’s remarks was his connection between those who “will vote for [Obama] no matter what” and those who are not paying income tax. It was incorrect then, and it’s still incorrect today to assume a strong connection between income taxes paid and voting behavior.

Romney’s running mate, Paul Ryan, also expressed some regrets about similar rhetoric in 2016. Rick Scott was a governor of Florida during the Romney-Ryan campaign, and is tasked with winning elections for Senate Republicans now. He should know better than to base his electoral theories on a famously losing argument.

Not even wrong

There’s a phrase often attributed to the acerbic but brilliant physicist Wolfgang Pauli: “not even wrong.” It is used to describe ideas that aren’t just wrong in an ordinary way, but rather, so incoherent that they don’t even have any falsifiable substance to disagree with.

That’s a little bit how I feel about Rick Scott’s tax idea. After you look at his exceptions and walkbacks and false premises, I’m not sure there is any content to this plan to actually argue about.

Consider the types of people who pay no income tax. One type is lower-income seniors. Some Social Security benefits are excluded from taxable income, and seniors also benefit from a larger standard deduction. Scott vows to exclude them from his tax hike proposal, stating in his WSJ op-ed that “retirees have paid plenty.”

Another type is working Americans with low incomes. Many of these have their income tax liability wiped out by the standard deduction—and by tax credits like the earned income tax credit or the child tax credit. These policies are written into the income tax code by law, and can reduce many working taxpayers’ liability to zero or less. Scott appears to demur on taxing this group, stating in his WSJ op-ed that “working Americans already pay taxes on their income.”

This is true in the sense that they pay payroll taxes, but if payroll taxes count as taxes on income for Scott’s purposes, his initial claim about the large number of people who pay no income tax is no longer true.

Analysis done at the time of Mitt Romney’s remarks suggest that seniors were the larger of the two groups of filers with zero liability. But given the expansions of the child tax credit in recent years, these two groups may be closer to equal in size.

A final type, perhaps the closest thing to true “nonpayers”, is people with no reported earned income. There are many ways this could happen, and they don’t lend themselves to a one-size-fits-all solution. Maybe they are students or unpaid interns. Maybe they are earning money through selling drugs. Maybe they lost their job. Maybe they are paid under the table and no W2 is reported to the IRS. Or maybe their business took a loss this year.

Under most of these circumstances, the IRS has no way to secure the revenue even if they wanted to; there’s no known transaction on which to set up withholding. Some of these situations, like the drug dealers, are better addressed by non-tax policy solutions. For some others, like the students and temporarily unemployed, the easiest solution is just to wait for people to get jobs and tax them then.

Ultimately, Scott starts with a big idea and retreats rapidly from the practical applications until I’m not sure anything is left. Perhaps that’s the point.

Vaporware ideas are bad for parties

Some more cynical political veterans may guffaw at my earnest attempt to analyze this idea seriously. They might note that the point is simply to be talked about, to build an email list, and to get the less sophisticated people excited. Then, when you get elected, you ignore the idea and do something else entirely. But I think this is a mistake, especially for someone—like Scott—in a party leadership role.

For one thing, if you want to come up with a fake policy just for show, you can invent something a lot more popular than raising taxes. For example, in 2020, Vice President Kamala Harris, then a senator running for President, simply offered to give everyone $2,000 a month until the pandemic ended. That was a fake policy, too, but a much more appetizing one than raising taxes.

For another thing, building people up towards ideas you don’t intend to act on is a recipe for pain later. President Joe Biden and Democratic leadership are constantly hounded about past promises, including the $2,000 monthly payments and forgiving student loan debts. Perhaps it was worth it to campaign on those issues, even if they were unable to deliver later. But failing to deliver has real political costs.

If you’re a backbencher looking to raise your political profile, it makes sense to put out some wild vaporware proposals in order to draw attention to yourself. But if you are acting as a spokesperson for more of the party, or even just attempting to build a solid national profile, your ideas should not be liabilities. McConnell’s rebuke of Scott was just. It should have been the last word.