The problem with Milton Friedman's idea for student loans

Income share agreements suffer from a problem called adverse selection.

Regulators at the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) dealt a blow Tuesday to income share agreements (ISAs), a creative product for financing higher education.

ISAs provide students with money to pay for their schooling, and in exchange, the students pay a percentage of their income (subject to limitations) after graduating.

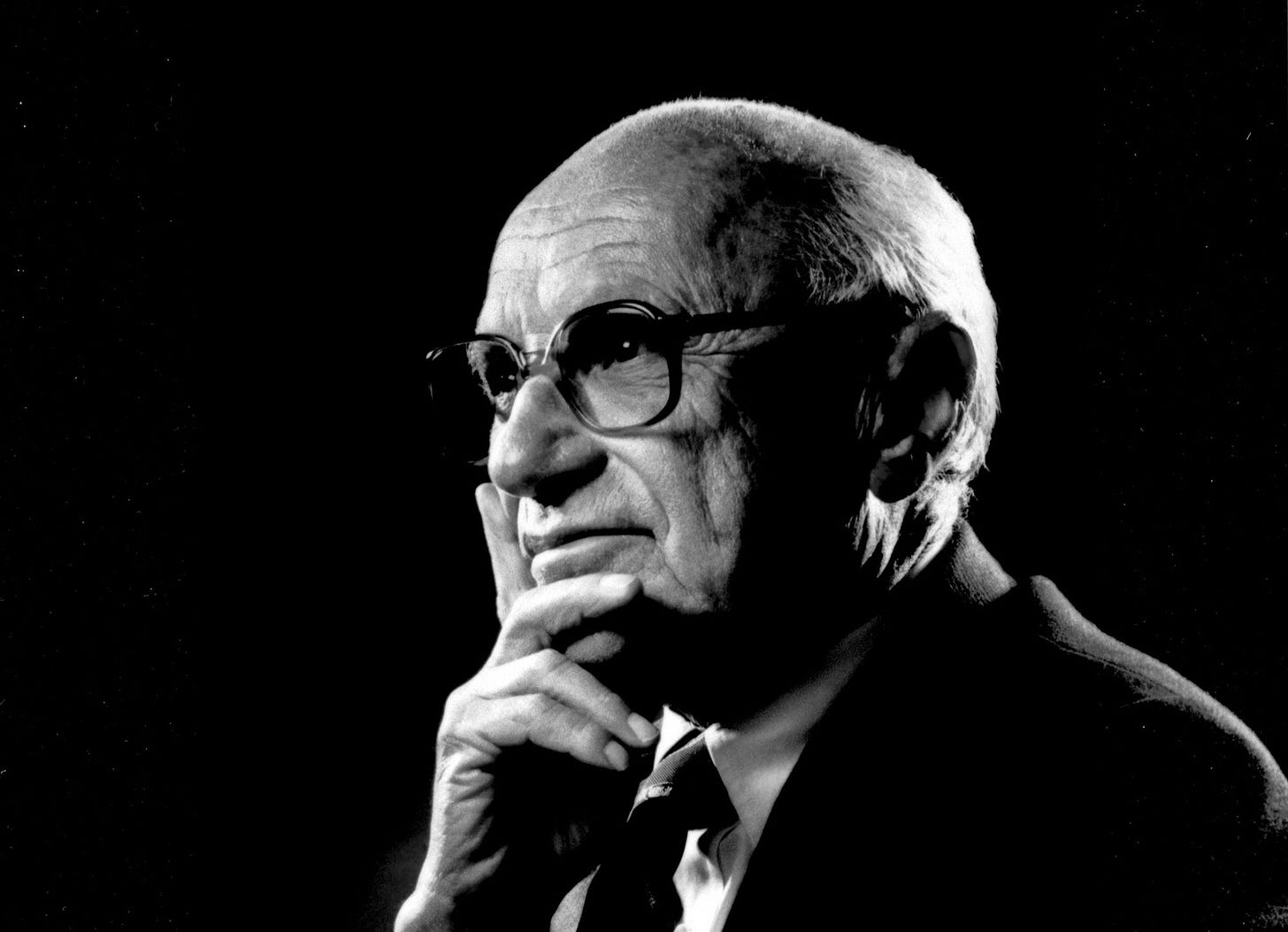

ISAs were first proposed in a 1955 Milton Friedman essay, and in theory, they have a lot of benefits. But they only fill a small role in practice. They have some intrinsic limitations, even in theory. Furthermore, the federal government takes a large role in financing education. ISAs mostly compete in the private loan market as supplements to federal loans.

There is reason to think ISAs could be good for students. Students need money to pay for school, but might not know how successful they will be at getting a job after graduation, or how much they will earn. A payment that varies with income helps smooth out risk relative to a fixed payment.

ISAs could also be helpful for the market as a whole by giving lenders skin in the game. If a student doesn’t get a job, the lender doesn’t get paid. If a lot of students from the same program don’t get jobs, then the lender stops financing that program. If there are scammy higher-ed products that offer poor job opportunities for their tuition costs, this mechanism would help cull them by cutting off their finances.

But despite their theoretical benefits, ISAs remain a niche product. Some serious schools like Purdue and University of Utah offer ISAs, but they are more the exception than the rule. A 2016 American Enterprise Institute report acknowledged “few ISAs exist at present, and we do not know if students would actually prefer them as much as economic theory might suggest.”

Overall, ISAs are a worthwhile experiment with some benefits and some flaws. Tuesday’s CFPB ruling was too harsh in an area that should be open to experimental approaches.

The CFPB ruled that Better Future Forward, a nonprofit that offers income share agreements, was in violation of the Consumer Financial Protection Act of 2010 on three counts. First, it had misrepresented the product by saying it wasn’t a loan. CFPB thought it was a loan. This point is semantic and debatable, but it fed into a second point: CFPB believes that Better Future Forward should have offered similar disclosures to those that would be provided for a loan product.

Finally, CFPB determined that Better Future Forward had effectively imposed a prepayment penalty, when it shouldn’t have. It ruled that Better Future Forward would need to eliminate that penalty. This point, in particular, unnecessarily exacerbates some of the pre-existing problems with ISAs.

ISAs have a potentially fatal flaw

The biggest problem for income share agreements would persist even in the absence of any regulatory pressure: people who expect to earn the most are less likely to sign up for ISAs.

In theory, ISAs can serve as “insurance” against having earnings lower than you hoped for. But insurance markets are potentially vulnerable to what economists call adverse selection: the people who need the insurance most sign up, and the people who don’t need it drop it.

In this case, the people with the best earning potential would exit the ISA market, and the ISA pools will fill mostly with lower earners who don’t repay very much or very fast. In theory, the lender could offer people with higher earning potential more favorable terms to draw them back in. But the lender has a limited ability to identify those folks, so it can't do this sufficiently to make the math work. The ISA agreement becomes unprofitable for lenders unless it offers unfavorable terms to everyone.

The same day that the CFPB decision was announced, economists Daniel Herbst and Nathaniel Hendren released a paper describing and quantifying this thesis. Their key finding was that students know important things that their lenders don’t. The researchers were able to use a 2012 survey that asked students questions like how much they expected to earn after school. They then matched that survey with more visible (“observable”) information about those students. They found that even after controlling for all the observable characteristics, like major, the students’ own subjective beliefs still had substantial predictive power.

The result: the students that plan or expect to earn high incomes know that income sharing is a bad deal for them, and they vamoose. So in order to break even on the remaining students, the income share agreement has to raise prices. By the Herbst and Hendren’s estimate, the typical student may have to pay $1.64 in present value for every $1 they borrow—not to fund lenders’ profits, but merely to make up for lower-earning students.

This is not a great deal, even for the average student. The market might “unravel” if it cannot attract sufficient numbers of high-earning students.

A future in doubt

The CFPB ruling has the potential to make the problem described by Herbst and Hendren even more severe: one CFPB finding was that Better Future Forward’s previous contracts effectively imposed a prepayment penalty on individuals who want to repay early. The CFPB ruled that the organization would need to essentially give people a way to buy out of their income share agreement.

Such an option would help high-income earners exit the pool even faster. This would be great for the high-income earners, all else equal, but in the longer run the income share pool would suffer even more quickly from the loss of its best earners.

I believe the CFPB got this decision wrong. On any loan, prepayment is a costly option. It’s not free, it’s an extra feature that lenders would otherwise charge for through higher interest rates. From the lender’s perspective, there’s a risk that interest rates will fall, the borrower will repay, and the lender will have to loan to someone else at lower interest. They therefore need to charge higher interest rates on pre-payable loans, relative to non-prepayable loans, in order to break even.

For some borrowers, the prepayment option might not be worth it. For example, companies and governments forgo it to get lower rates. The ISA market is probably like this; borrowers do value the prepayment option (it comes up in the AEI survey on ISAs) but given the intense adverse selection pressure on the market, lenders likely value it more.

In mandating a prepayment ability, CFPB is looking at ISAs too much like a mortgage or auto loan, and not enough like an insurance product. For auto or car loans, there is a good reason for the standard product to be prepayable: the borrower might want to sell the house or car. You need borrowers to be able to hop in and out of debt contracts in order for the market to function.

By contrast, insurance contracts need to be written so that the insured can’t hop in and out of the pool depending on which outcome is better for them. ISAs likely need the same.

Convergent evolution

One long-known fact in biology is that sometimes different organisms with different heritage often end up evolving to have similar properties. For example, a dolphin is a mammal, a swordfish is a ray-finned fish, and an ichthyosaur was a reptile from the time of the dinosaurs, but all three creatures separately converged on the same streamlined swimming shape.

Something similar has been happening in education finance: debt contracts and income share agreements have been adopting each other’s best properties and becoming more similar over time.

The AEI survey notes that many students skeptical of ISAs worry about upside risk, or feel like insurance is “betting against yourself.” Income share agreements tend to have maximum repayment caps, so that future high earners don’t feel as motivated to exit the market, which helps with both the subjective feeling of “betting against oneself” and with the adverse selection problem.

On the flipside, federal student loans have had income-contingent repayment options since 1994, which makes them work a little more like an ISA. Furthermore, they have the possibility of forgiveness for certain public service jobs. Private lenders are less income-based than the federal program, but they necessarily do account somewhat for borrowers unable to repay; for example, through forbearance programs.

In other words, the two different types of financing may eventually end up pretty similar to each other. The income sharing plans have moved in the direction of fixed repayment plans, and the fixed repayment plans move in the direction of income sharing.

This solution isn’t entirely satisfying: the insurance market for low earnings won’t be as complete as we might like. In an ideal world, people might like more insurance, but could be precluded by adverse selection. Herbst and Hendren suggest that a well-thought-out subsidy scheme might be able to help avert this, though this is likely harder than it sounds.

Strike at the source

Overall, this market would benefit from a lighter regulatory touch. There is no obvious best practice for lending; it has to balance competing concerns: insurance, adverse selection, ability to pay, and feelings of fairness. The right balance will probably best be found through flexibility, choice, and allowing products to evolve.

If there is a time for a heavier regulatory touch, it is to strike at the source. Scammy programs continue to exist, even at schools with otherwise sterling reputations. For example, a Wall Street Journal investigation of Columbia’s MFA program in film was astonishing: students racked up a median debt of $181,000, and half of them made less than $30,000 per year two years after completing the program. In egregious cases like this, the problem isn’t the financing, it’s the product.

The federal program for student lending is not nearly as ruthless at cutting out poor performers as private sector finance would be. But if the federal government is to continue financing the bulk of higher education, it should fiercely protect that investment from being fleeced by low-quality programs.

Liberal regulators, as a class, afford too much latitude to education products, and too little to financial products like ISAs. Conversely, free marketers have probably been too optimistic about ISAs. Even in a more favorable regulatory environment, adverse selection substantially limits their attractiveness.