Republicans won’t help on the debt limit—their voters won’t let them

Democrats have often underrated the deadly sincerity of Republican voters on this issue.

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has warned that Congress needs to raise the debt ceiling, a legal limit on how much debt the Treasury can issue, by October 18th. This is a familiar drama, one so long-standing that it was covered in an episode of a show called The West Wing, which originally aired in 2005 when I was too young to vote. But the stakes of this fight have escalated substantially over the last sixteen years.

Budget experts all agree that the debt ceiling needs to be raised. They patiently explain that breaching the debt ceiling wouldn’t promote better policies. It would just lead to chaos, as the Treasury cannot reliably make the payments Congress has already committed it to.

The debt ceiling is arguably a procedural bug: Congress can pass laws that create deficits, but then balk at allowing the Treasury to actually execute those laws, without offering clear instructions on what is supposed to happen next.

But while raising the debt ceiling is necessary, it’s also deeply unpopular; this leads to dramatic political episodes every couple of years as “necessary” and “popular” come into conflict. The Treasury secretary always attempts to do the right thing and enlists the president, but members of Congress face pressure to do the wrong thing. The result is that Congress, led by the president’s party, does the absolute bare minimum to get the job done.

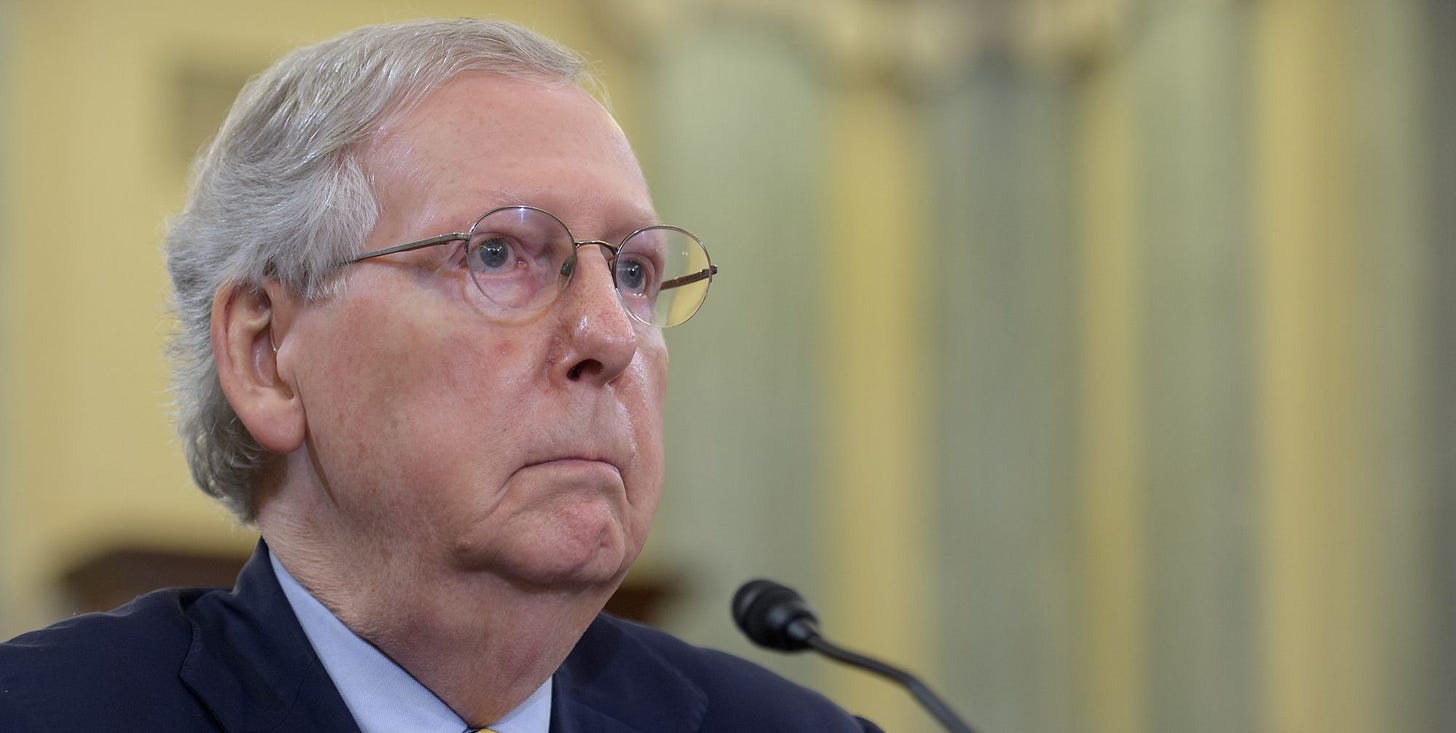

Right now Democrats, who control the White House and both houses of Congress, are asking Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) and his Senate caucus to do more than the bare minimum. This is a fool’s errand. McConnell is not going to budge, and keeping the debt in the news is only going to harm Democrats. McConnell has left Democrats just enough room to get the job done. It’s in their own interest—as well as the national interest—for Democrats to get it done with a minimum of further drama.

Congress has two options

There are two basic ways that Congress could raise the debt ceiling. One is to pass a bill through the standard legislative process, known as regular order. Such a bill would be subject to the filibuster, which means that Democrats would need to convince at least 10 Republican senators to vote to end debate on the bill (known as cloture) even if they ultimately vote against it. Debt ceiling bills have passed with fewer than 60 votes in the past. But in today’s political climate, many see a vote for cloture as tantamount to voting for the underlying legislation.

The other possibility is to use a procedure called reconciliation that shields certain budget-related bills from the filibuster. If Democrats chose this route they could raise the debt ceiling despite unified Republican opposition.

But doing this would complicate their larger fiscal agenda. Congressional Democrats are currently haggling over a spending package that could be as large as $3.5 trillion over 10 years. It’s not clear if negotiations over that bill will complete before the mid-October deadline to raise the debt ceiling. Congress can only consider one reconciliation bill at a time, so raising the debt ceiling via a stand-alone reconciliation bill could derail work on the spending package.

Naturally, Democrats would prefer to raise the debt ceiling through regular order, with Republican help. An additional downside to reconciliation, from Democrats’ perspective, is that federal law requires a reconciliation bill to specify a dollar figure for the debt ceiling. That’s in contrast to the recent practice of simply suspending the debt ceiling until a future date—something that’s possible if the debt limit is raised through regular order. Democrats worry that if they choose a specific dollar figure in the trillions, it could become fodder for Republican attacks.

Republicans naturally prefer to see Democrats do it through a reconciliation bill without their help. For their part, Democrats have sought to portray McConnell as an obstructionist for refusing to supply the votes to pass a debt limit increase through regular order.

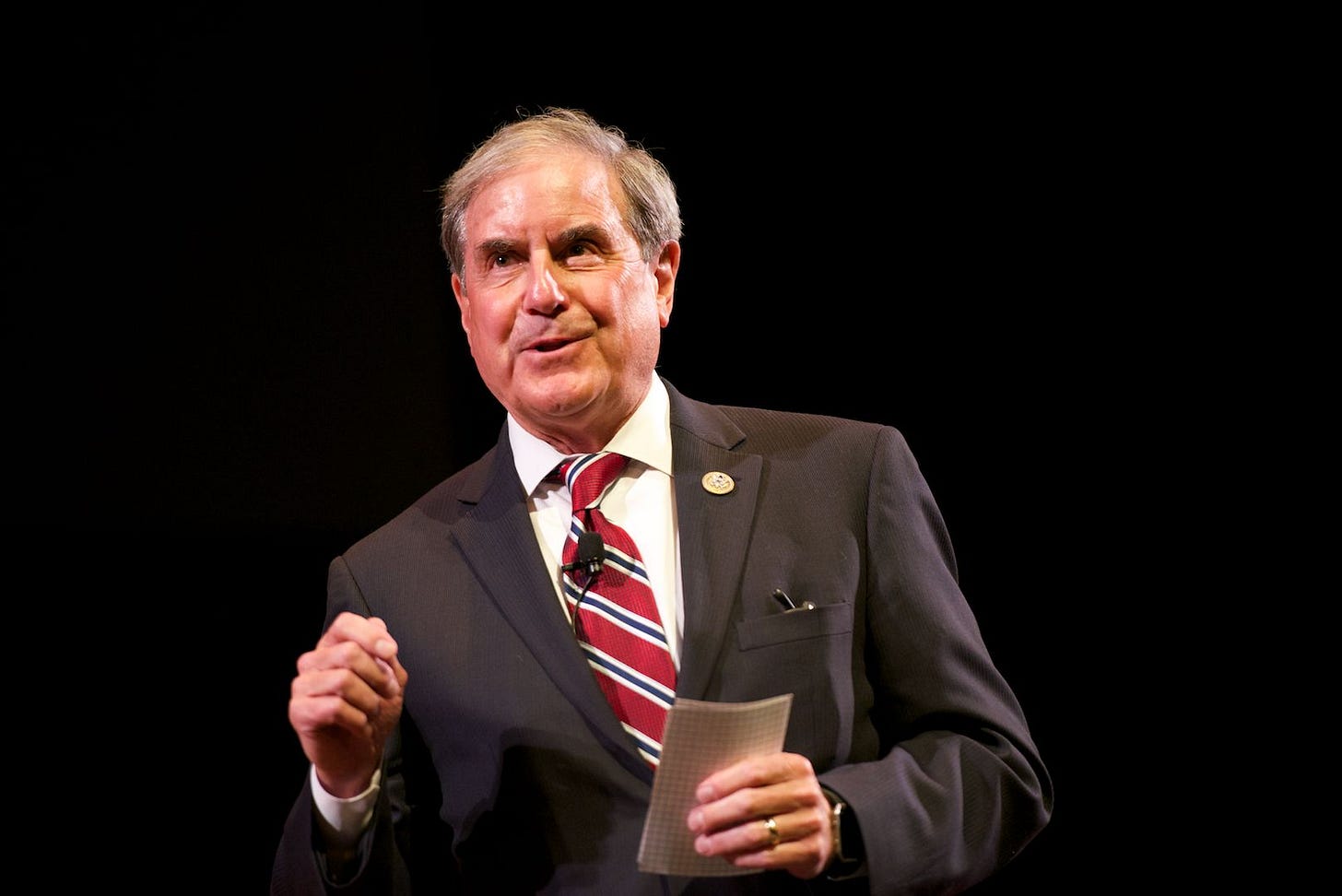

In what was perhaps a Kinsley gaffe, John Yarmuth (D-KY), the House Budget Chair, explained: “We can do it through reconciliation. Leadership has said they don't want to do that. The reason is if we do that through reconciliation, we actually have to specify a number."

If you believe the debt ceiling is a serious issue, and one not to play games with, then you have a possible answer here: Democratic leadership should just get it done through reconciliation. This is what Tim Kaine (D-VA), for example, thinks. But instead, Democratic leadership have chosen to play a game with McConnell, and it is a game they will lose.

Borrowing is unpopular

Increasing the national debt is not popular. I wish it were otherwise. A government needs to issue financial assets for its people to have stable finances of their own; you need to give them some money to play with. Interest rates are a good measure of a government’s capacity to service debt, and interest rates have been low for a long time, and are expected to remain so.

But the polling is pretty clear. In Ipsos polling commissioned by the debt-hawkish Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, 75% of respondents agreed that “we should worry about the national debt.” 75% agreed that “too much federal debt can hurt the economy.” 66% agreed that “the national debt is an unfair legacy being left to younger generations.”

Experts rightly note that hitting the debt ceiling doesn’t curb overspending; it just means that federal checks start bouncing, and that’s bad. It might therefore make sense for members of Congress—even ones who support reducing the deficit—to lift the debt ceiling.

But most people don’t have any of this context when they hear about a debt ceiling vote. Instead, they hear distorted bad-faith representations in ads: “Senator X voted to increase the national debt.”

Voters might like the tax cuts or new spending that more debt makes possible. But a vote to raise the debt ceiling doesn’t appear to have any offsetting benefit. It’s not “higher debt to pay for children’s healthcare,” for instance. On the surface, it’s just higher debt.

Raising the debt ceiling polls terribly. In a 2011 showdown over the debt limit, for example, Gallup found that about twice as many people supported voting against the debt limit rather than for it. 42% and 47% against, on two separate dates, just 22% and 19% for. Now you might hope that voters would learn from the first showdown, remember the arguments for, and support it more the next time. But that doesn’t seem to be the case. A 2013 Wall Street Journal/NBC poll put “should raise” at just 22 percent, and “should not raise” at 44 percent.

These numbers are grim. Members of Congress who want happy constituents don’t want to vote for this. They want other people to vote for it.

President Barack Obama has been on both sides of the conflict. He gave a floor speech against raising the debt limit for George W. Bush in 2006, and voted together with Joe Biden against raising the limit. Of course, he reversed his position when he became President.

He later laid out the incentives behind what he called a “political vote, as opposed to doing what was important for the country.”

But those incentives are different for the president’s party: “When you’re a Senator, traditionally what’s happened is this is always a lousy vote. Nobody likes to be tagged as having increased the debt limit for the United States by a trillion dollars or a trillion and a half, whatever the number is. And so, traditionally the president’s party … bears the burden of passing it.”

Republican voters are especially anti-debt

Republicans are under especially strong political pressure to vote no. Their base has more visceral anti-debt sentiments. Democrats have some anti-debt sentiment, to be sure. But it is the product of Robert Rubin-era views of responsible governance, and people who hold Rubinesque views tend to trust expert opinion on issues like the debt ceiling. Furthermore, anti-debt sentiment among Democrats seems to be abating as interest rates have fallen.

Republican views on this come from the id.

“The harsh truth is that we have no money left. We’ve spent it all. It’s gone. This year, if we do nothing at all except honor our existing commitments, we are going to spend $3.1 trillion that we don’t have,” roars National Review’s Charles C.W. Cooke. “And the Democrats want to make it worse?”

I disagree with this view today, but that’s the product of a lot of thinking and a couple of degrees in economics. If you had asked me about debt before I did those studies, I would have absolutely agreed with Cooke.

Critics can point to instances of Republican hypocrisy on this issue. Republicans have voted for deficit-expanding bills like the 2017 tax cuts. Jonathan Chait, a Democrat-leaning pundit, took the conservative magazine National Review to task on Twitter: “it seems like [National Review]’s role is to tout the deficit-increasing tax cuts under GOP presidents, then shuffle those folks to the rear and bring out the debt hawks when party control changes.”

Chait isn’t completely wrong, but Republicans have (unfortunately in my view) been far more consistent on this issue than Chait wants to admit. Anti-debt Republicans regularly hamper their own presidents’ priorities as well. Trump’s 2017 tax cuts were much smaller than he wanted, primarily due to deficit hawks like then-Senator Bob Corker (R-TN).

And much of the recent deficit spending during the Trump administration was actually done in September 2020 and December 2020 deals with Speaker Pelosi (D-CA), over the objections of many Republican members.

But perhaps the most important example comes from a 2017 debt ceiling hike deal, negotiated between Trump and Pelosi and Schumer (even though Republicans had the majority in both houses.) Trump agreed to additional nondefense spending and made concessions to Democrats on immigration in exchange for their votes—and they delivered. Meanwhile, many Republicans still voted against the deal. Heritage Action labeled a vote against as a “key vote.” Ben Shapiro, arguably the right’s most influential online media personality, blasted the deal.

If you’re a deficit dove, like me, you might be frustrated with those Republican votes against the deals. In fact, refusing to help Trump on a necessary priority forced Trump to partner with Democrats. In my view, we would be lucky to have a Republican Party with the competence and cleverness that Chait attributes to them. But in opposing those Trump-Pelosi deals, personalities on the right demonstrated sincerity, not hypocrisy.

Democrats need it more

There is also a situational factor that drives Republicans to vote against lifting the limit: it is set to run out on October 18, while Democrats will likely still be working on their big spending bill. Republicans do not support the bill, and neither do their most engaged voters. The Senate Budget resolution that outlines the fiscal bill would allow (though not require) up to $1.75 trillion of additional borrowing. And even if they attempt to “pay for” the full bill in terms of Congressional Budget Office scoring, some “offsets” used in the process are likely to be accounting tricks, and some of the most expensive provisions are likely to be frontloaded. In other words, it is likely to cause some borrowing. And this will link it with the debt ceiling in voters’ minds.

Experts like to see the debt limit as entirely separate from fiscal policy decisions. As they see it, the debt limit is a procedural quirk that shouldn’t exist, but if we must have it, Congress should always vote to expand it when necessary. Meanwhile, they separately want us to support good fiscal policy, whatever that may be.

But that intellectual separation isn’t really possible outside the walls of stodgy think tanks.

Ultimately the path is pretty clear. Democrats need this more. Recent polling shows Democrats, who control every elected branch of the government, would receive more blame for a debt limit crisis than Republicans.

No one actually wants to see the ceiling breached. But McConnell isn’t going to commit his members to an unpopular vote. Instead, he will allow Democrats the time to get it done by themselves. McConnell may, for example, allow them to pass an extension of a few weeks, or help speed along the reconciliation process for the debt limit. But Republicans will provide no on-record votes.

From a Democratic perspective, continuing to argue about this is a mistake. Raising the salience of "debt," as a concept, is not beneficial while you are trying to get a spending bill done. Better to quickly raise the debt ceiling through reconciliation and move on to a more favorable argument.