Workers are enjoying the tightest labor market in decades

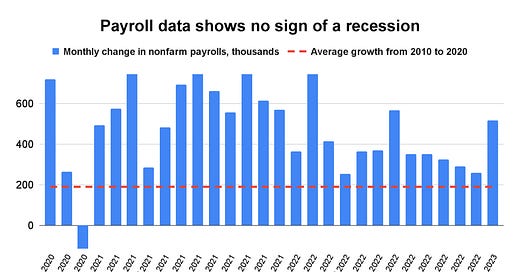

The latest job numbers suggest there’s no recession in sight.

The U.S. economy gained 517,000 jobs in January, crushing economists’ expectations. The unemployment rate fell to 3.4 percent, the lowest figure since 1953. In short, the labor market continues to defy economists’ predictions that we’re likely to have a recession in 2023.

Economists have been anticipating a recession because the Federal Reserve has been aggressively raising interest rates over the last year in an effort to bring down inflation. On Wednesday, the Fed raised rates another 0.25 percent and signaled that more rate hikes were likely in the future.

The campaign against inflation seems to be working. Last month the Bureau of Labor Statistics announced that prices rose 6.5 percent in the year ending December 2022. That’s the lowest inflation rate in more than a year, though it’s still well above the Fed’s 2 percent inflation target.

Big rate hikes often often lead to job losses, and in the second half of 2022, the labor market really did seem to be softening. The pace of job growth steadily declined between July and December. However, even December’s job growth figure was above the long-term average. And January’s gain of 517,000 was far above historical norms, suggesting that the job market is still getting tighter even as the Fed raises interest rates.

Indeed, I think the chart above actually understates how impressive that 517,000-job figure is.

The economy gained about 600,000 jobs per month, on average, over the course of 2021. So last month’s job growth doesn’t look that unusual when you compare it to the previous couple of years. But we have to remember that the job gains of 2021 came shortly after employers laid off a historically unprecedented 22 million people between February and April of 2020. Indeed, I started this chart in October 2020 because otherwise the huge labor market swings between February and September would make the rest of the chart unreadable.

A lot of that 2021 hiring was employers staffing back up to normal levels as the economy reopened. But we’re now three years past the start of the pandemic. Job growth today is mostly not pandemic rebound hiring. So to get a sense of just how impressive that 517,000-job figure is, it’s helpful to compare it to the pre-pandemic years.

Between 1990 and 2019, there was just one month when the economy gained more than 500,000 jobs: a 530,000-job gain in May 2010. Even if you adjust for population, there were only two other months, both during the 1990s boom, when the economy added jobs at a faster pace than it did last month.

Recent headlines have given a somewhat misleading impression because high interest rates have disproportionately affected the high-profile technology and media sectors. There have been a lot of articles about layoffs in Silicon Valley, and that’s reflected in data showing that the information sector lost 10,000 jobs, on net, between November 2022 and January 2023.

But those layoffs have been dwarfed by robust hiring in the leisure and hospitality sector—which gained 192,000 jobs between November and January—and health care—up 111,000 over two months.

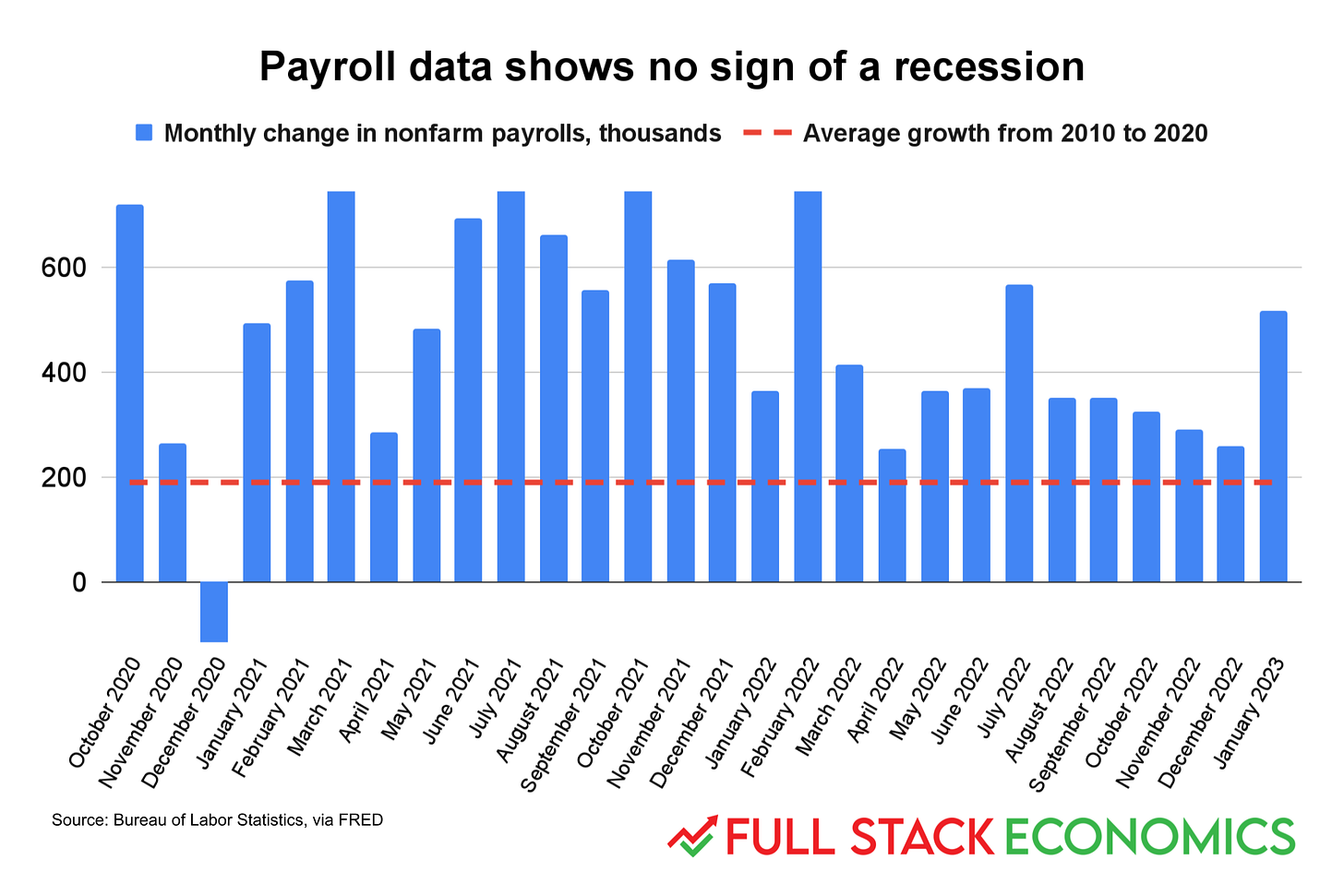

Here’s another way to look at the health of the job market:

This shows the ratio of workers to population for those between the ages of 25 to 54. This is a useful indicator because it excludes those over 55 (who may be retired) and those under 25 (who may be in school).

By this measure, the economy hasn’t quite rebounded to the January 2020 peak of 80.6 percent, but it’s very close at 80.2 percent. The 0.4 percent difference, combined with the ultra-low unemployment rate, makes me think there are still a few people being kept out of the labor market due to COVID.

Still, it’s remarkable how quickly the economy rebounded from the April 2020 low point. It took less than two years for the prime-age employment to population ratio to rise from less than 70 percent in April 2020 to 80.1 percent in March 2022.

In contrast, it took a full decade for this measure to rise from 74.8 percent in December 2009 to 80.6 percent in January 2020. If the recovery of the 2010s had been as robust as the post-COVID recovery, we would have returned to the previous peak eight years earlier—in 2011 rather than 2019.

Slow wage growth isn’t all bad news

The least impressive part of today’s jobs data is wages. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, average wages rose by 0.3 percent between December and January, and by 4.4 percent over the last year. With the inflation rate well above 4.4 percent, this means most workers’ real wages have actually been falling.

That’s not great, but there are a few silver linings.

One is that wages are likely to be a lagging indicator. It takes a while for employees to notice they have bargaining power, demand higher wages, and for the resulting raises to go into effect. But if inflation continues to fall while the labor market stays strong—as seems increasingly likely—we may see the opposite process occur over the next couple of years. Inflation may fall back down to the Fed’s 2 per percent target, while wages continue to grow at a faster pace.

We’re also continuing to see a decline in wage inequality.

Tight labor markets are good for all workers, but they tend to be best for workers at the bottom end of the wage scale. The economic boom of the 1990s produced strong wage growth for low-paid workers, while the recessionary periods of the early 2000s and the early 2010s saw low-wage workers falling further behind highly compensated workers.

Since 2015, gains for low-wage workers have once again been exceeding those higher up the income scale. And the pandemic seems to have widened the gap.

As a result, workers at the bottom end of the income distribution have seen their wages almost keep pace with inflation over the last two years, while higher-paid workers have seen their real wages fall significantly behind.

A final upside of slow wage growth is that it should make the Federal Reserve feel more comfortable ending its campaign of rate hikes in the coming months. The Fed’s nightmare is a wage-price spiral where employees start expecting big raises to offset anticipated inflation, and employers automatically pass the costs on to consumers. If this feedback loop became entrenched, as it did in the 1970s, it could become much harder to bring down the inflation rate.

But the latest jobs report continues to show no sign of that happening. Wages are lagging behind inflation, they aren’t driving it. That should give Fed officials more confidence that inflation will continue coming down even if they bring their rate hikes to an end. Which makes it less likely that they’ll tighten too much and bring about the recession economists keep warning us about.

I find this article very helpful! You can't get perspective like this from reading traditional news sources like the WSJ.