Why Agatha Christie could afford a maid and a nanny but not a car

The counterintuitive principle that explains the modern world.

Agatha Christie’s autobiography, published posthumously in 1977, provides a fascinating window into the economic life of middle-class Britons a century ago. The year was 1919, the Great War had just ended, and Christie’s husband Archie had just been demobilized as an officer in the British military.

The couple’s annual income was around around £700 ($50,000 in today’s dollars)—£500 ($36,000) from his salary and another £200 ($14,000) in passive income.

They rented a fourth-floor walk-up apartment in London with four bedrooms, two sitting rooms, and a “nice outlook on green.” The rent was £90 for a year ($530 per month in today’s dollars). To keep it tidy, they hired a live-in maid for £36 ($2,600) per year, which Christie described as “an enormous sum in those days.”

The couple was expecting their first child, a girl, and they hired a nurse to look after her. Still, Christie didn’t consider herself wealthy.

“Looking back, it seems to me extraordinary that we should have contemplated having both a nurse and a servant,” Christie wrote. “But they were considered essentials of life in those days, and were the last things we would have thought of dispensing with. To have committed the extravagance of a car, for instance, would never have entered our minds. Only the rich had cars.”

In 1919, Ford’s Model T cost £170—around $12,000 in 2022 dollars. So a car was worth about three months of income for the Christie family—but almost five years of income for their maid!

By modern standards, these numbers seem totally out of whack. An American family today with a household income of $50,000 might have one or even two cars. But they definitely wouldn’t have a live-in maid or nanny. Even if it were legal today to offer someone a job that paid $2,600 per year, nobody would take it.

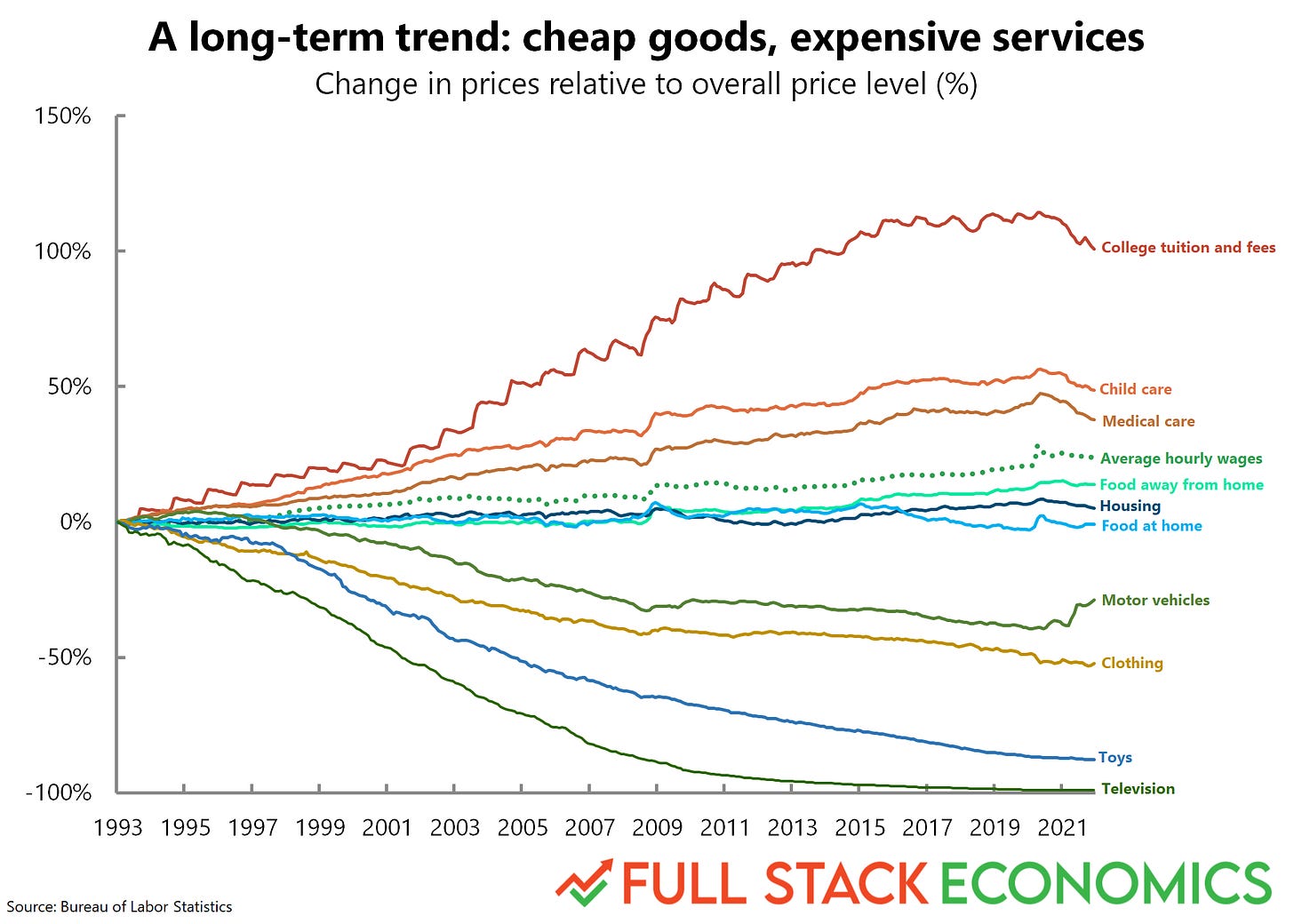

The price shifts Christie observed during her lifetime continued to widen after her death. Here’s a chart (from last Thursday’s “18 charts that explain the modern economy”) that illustrates the phenomenon:

As you can see, cars aren’t the only things that get cheaper over time. In the last 30 years, clothing, children’s toys, and televisions have all gotten steadily cheaper as well—as have lots of other products not on the chart.

In her autobiography, Christie notes that when she was a kid, “girls had usually not more than three evening dresses, and they had to last you for some years.” And by “girls” she meant girls in families well-off enough to have a couple of servants. Today, girls in affluent families tend to have closets overflowing with clothes.

It’s one of the most important economic mysteries of the modern world. While the material things in life are cheaper than ever, labor-intensive services are getting more and more expensive. Middle-class Americans today have little trouble affording a car, but they struggle to afford a spot in day care. Only the rich have nannies.

Who is to blame? Some paint the government as the villain, blaming excessive regulations and poorly targeted subsidies. They aren’t entirely wrong. But the main cause is something more fundamental—and not actually sinister at all.

Baumol’s wage bonus

Back in the 1960s, the economist William Baumol observed that it took exactly as much labor to play a string quartet in 1965 as it did in 1865—in economics jargon, violinists hadn’t gotten any more productive. Yet the wages of a professional violinist in 1965 were a lot higher than in 1865.

The basic reason for this is that workers in other industries were getting more productive, and that gave musicians bargaining power. If an orchestra didn’t pay musicians in line with economy-wide norms, it would constantly lose talent as its musicians decided to become plumbers or accountants instead. So over time, the incomes of professional musicians have risen.

Today economists call this phenomenon “Baumol's cost disease,” and they see it as one of the most important forces driving the price trends in my chart above. I think it’s unfortunate that this bit of economics jargon is framed in negative terms. From my perspective as a parent, it might be a bummer that child care costs are rising. But my daughter’s nanny probably doesn’t see it that way—the Baumol effect means her income goes up.

Rising productivity in one industry not only drives higher wages in that industry, it puts upward pressure on wages across the economy. When you put it that way, the phenomenon doesn’t seem so much like a “disease.” It might be better if we talked about the “Baumol bonus” workers get when other workers become more productive.

Moreover, there are good reasons for some industries to be resistant to the kind of automation that drives down prices. Child care is the most obvious example. Even if someone managed to invent a robot nanny that kept kids safe as well as a human being, I wouldn’t want it to take care of my baby. I bet you wouldn’t either.

Or take the coffee industry. We already have machines that make coffee. Someone could probably design a robot to automatically brew Starbucks-caliber coffee, potentially putting baristas out of work.

But Starbucks would never adopt such a robot, because they know customers wouldn’t like it. A decade ago, the Wall Street Journal reported that Starbucks was “telling its harried baristas to slow down.” The company had been getting complaints that the company had “reduced the fine art of coffee making to a mechanized process with all the romance of an assembly line.” So baristas were “told to stop making multiple drinks at the same time.”

Inefficient use of labor helps to make a visit to Starbucks a luxury experience. As Americans get wealthier, we spend more money on luxuries like this. That will cause the official inflation rate to be higher than it would have been otherwise. But that’s not a sign that Starbucks is doing something wrong—the company is giving customers what they want.

Did the government do it?

Many people who see the first chart in this article immediately notice that the highest-cost industries are the ones with the most government involvement. Health care and education are two of the most heavily subsidized and regulated industries. Child care is subject to extensive regulation as well.

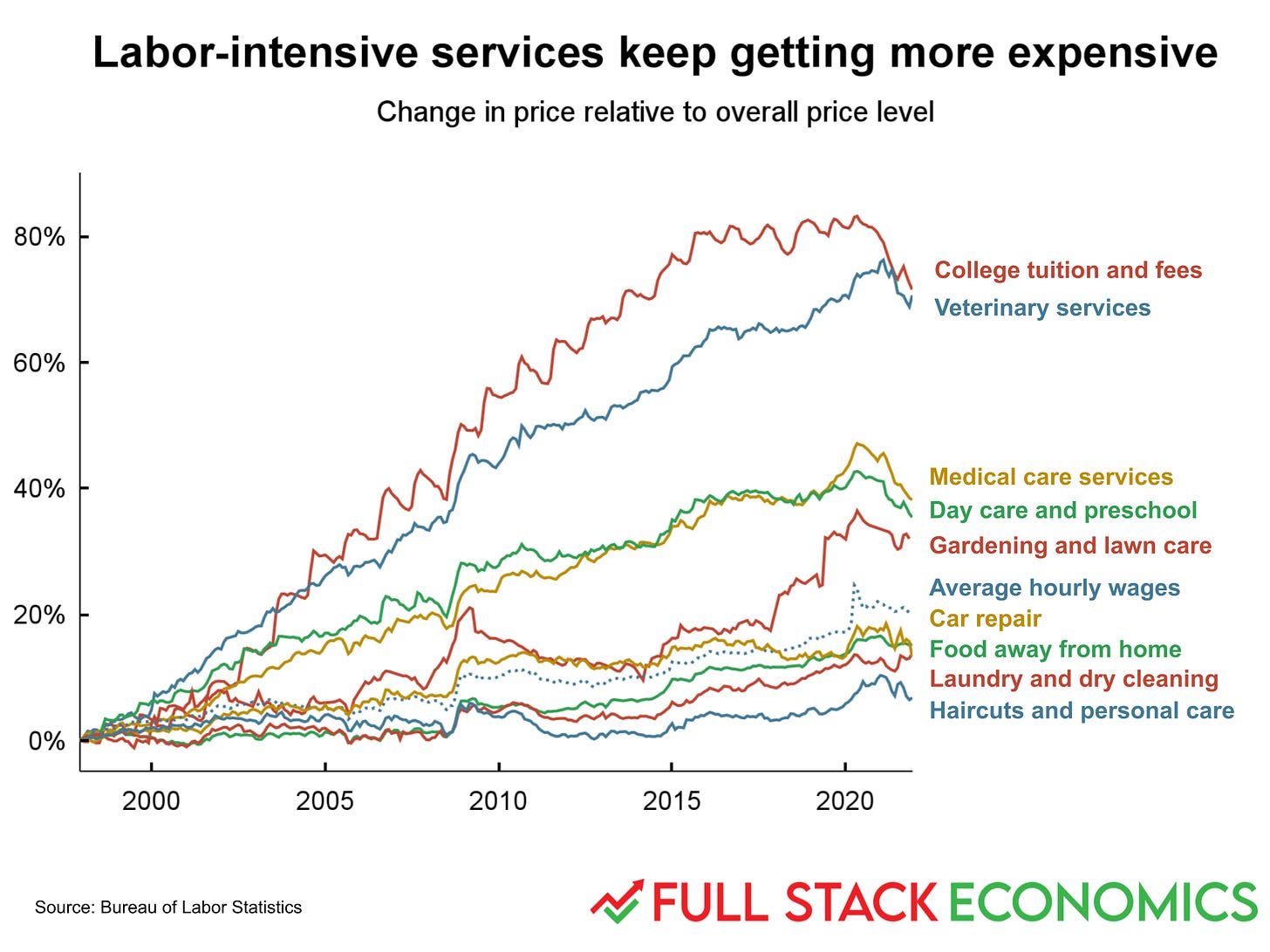

So how much blame do governments deserve? To help answer this question, I created another version of the chart that shows college tuition, medical care, and child care services alongside a bunch of other labor-intensive services:

Every one of these industries has grown in price faster than the overall price level. None of them has a trajectory like televisions, getting cheaper each year. In some cases—as with child care and haircuts—that’s because they inherently require direct interaction between customers and service providers. In other cases—like lawn care and dry cleaning—you could imagine automating more of the work, but for whatever reason there hasn’t been much progress.

At the same time, I would not say this chart provides strong evidence for the thesis that cost increases are primarily driven by government policies. For example, the government doesn’t regulate or subsidize veterinary services nearly as much as it does health care services. Yet veterinary services have had a high inflation rate over the last 25 years. Veterinarians do need a license to practice in most states, but that’s also true for salons and barbershops, an industry that has had less inflation than restaurants or lawn care services.

So what does explain the rather different trajectories of these services? I suspect that rising wealth—and, to some extent, rising income inequality—plays a big role.

Take college tuition. Wealthy American parents are willing to pay a lot of money to get their kids into the best university. And the “best university” isn’t just about the quality of instruction; it’s also about prestige and the caliber of the other students. This means that the supply of “good schools” is inelastic. Anybody can start a new university, but even a well-funded school would start out near the bottom of the rankings and take decades to work its way up.

I do think government policy probably contributes to rising college costs with subsidized loans and rules preventing student loans from being discharged in bankruptcy. These measures enable students to borrow more—and hence enable schools to charge more tuition than they would otherwise. But even without those policies, the rising incomes of affluent parents would probably be pushing tuition upward faster than inflation.

Similarly, I think veterinary care is getting more expensive because people are becoming more and more willing to spend lavishly to take care of their pets when they get sick. Last year, Marketplace talked to one expert who said that she was “seeing a spike in cancer diagnoses in pets.” She noted that “the full treatment, including surgery and chemotherapy, can reach between $8,000 and $10,000 for a dog or cat.” Spending on veterinary care doubled between 2010 and 2021, even after adjusting for inflation. This partly reflects a cultural shift where more people treat their pets like members of the family. But they couldn’t do that unless they had $8,000 to $10,000 to spare.

Here, too, government may play a role, since state licensing rules may be limiting the number of people who can become veterinarians. But it’s not clear the industry could keep up with rapid demand growth even without those restrictions. It takes a long time to expand the training pipeline for a skilled profession like veterinarians.

Long-term inflation adjustments are kind of made up

At the start of this piece, I stated that the Christies’ income of £700 was equivalent to $50,000 in today’s dollars. But price comparisons like this over long periods of time are (in the words of my colleague Alan Cole) “at least a little bit made up.”

To get that $50,000 figure, I used the Bank of England’s inflation calculator to convert 1919 pounds to 2020 pounds and got £36,962.56—$50,000 at current exchange rates. But there’s reason to be skeptical of inflation conversions like this—or at least to treat them as rough approximations.

To compute an inflation index, government statisticians survey consumers and develop a representative list of the goods and services the typical consumer buys. Then they determine the price of each item on the list from one year to the next, and add all these prices up.

The problem with doing this over long time periods—like between 1919 and 2020—is that the things families buy in the two periods are radically different. A family in 1919 bought relatively few clothes, and a lot of them were hand-tailored. A wealthy family in 1919 purchased a lot of housecleaning labor, but likely did not own a vacuum cleaner, dishwasher, washing machine, or other household appliances. Most families didn’t own a car. They definitely did not own a smartphone, a personal computer, or a television.

So when I say Agatha Christie and her husband had an income equivalent to $50,000, that doesn’t mean they had exactly the same lifestyle as a modern American family with that income. In some ways, the Christies lived much better. For example, Christie notes that having servants made it easy to throw elaborate multi-course dinner parties.

On the other hand, the Christies in 1919 lacked access to modern medicine. They couldn’t take a flight across the Atlantic at any price. They couldn’t watch television or look anything up on the internet. If a 1919 family had a car, it was slow, unreliable, dangerous, and lacked modern features like an automatic transmission, power steering, or air conditioning. They likely would not have had access to fresh fruit and vegetables year-round, as Americans and Britons do today.

Ultimately, whether £700 in 1919 is worth more or less than $50,000 in 2020 is not a purely objective question. The 1919 income provides a better lifestyle in some respects and a worse lifestyle in others.

This is relevant for contemporary debates about how the standard of living has changed in recent decades. You’ll sometimes see pundits declare that American workers haven’t seen their standards of living improve since the 1960s. Economists can and do debate the methodology underlying such claims. But we should bear in mind that this is ultimately not just a statistical question.

If you want to argue that workers were better off in the 1960s, you can focus on the rising cost of health care, child care, and education. If you want to make the case that workers live better today, you can point to the falling cost of food and clothing, as well as the dramatically better value provided by cars, televisions, and other manufactured goods.

There’s no purely objective way to decide between these two perspectives. Different people place different importance on different goods and services. I think average American workers today are substantially better off today than they were in 1962. But that’s at least partly a matter of opinion, not something that I’ll ever be able to prove objectively.

What we can say, however, is that there are far more people who make $50,000 in today’s America than earned £700 in 1919 Britain. Agatha Christie claimed she wasn’t rich, but her income was far above average in 1919. In contrast, most American households earn more than $50,000.

Very few Americans have maids today because we don’t have a substantial labor force willing to work for a few thousand dollars a year. That in itself is a clear sign that living standards have risen substantially, even if reasonable people can disagree about exactly how large the improvement has been.