Policymakers still aren’t taking inflation seriously enough

It's time for doves to declare "mission accomplished" on full employment, and pivot to efficiency and stable demand.

In 2020, Congress turned on the spending spigots to ensure a robust recovery from the COVID recession. Congress passed three big spending bills—in March 2020, December 2020, and March 2021. The Federal Reserve also kept interest rates at zero, allowing money to be lent generously around the economy, financing new spending.

I thought—and still think—these policies made sense at the time. I was worried about a repeat of the slow, painful recovery after the 2008 crash. Happily, we didn’t repeat that experience in 2021. The economy boomed, and the labor force participation rate rapidly returned to pre-COVID levels.

But the success of those policies has put us in a dramatically different economic situation. Today inflation, not unemployment, is our biggest economic concern.

Prices rose 8.5 percent over the last year, and markets expect high inflation to continue for years to come. On Thursday, the 10-year breakeven inflation rate—which reflects how much inflation the market expects over the next ten years—rose above 3 percent for the first time in many years.

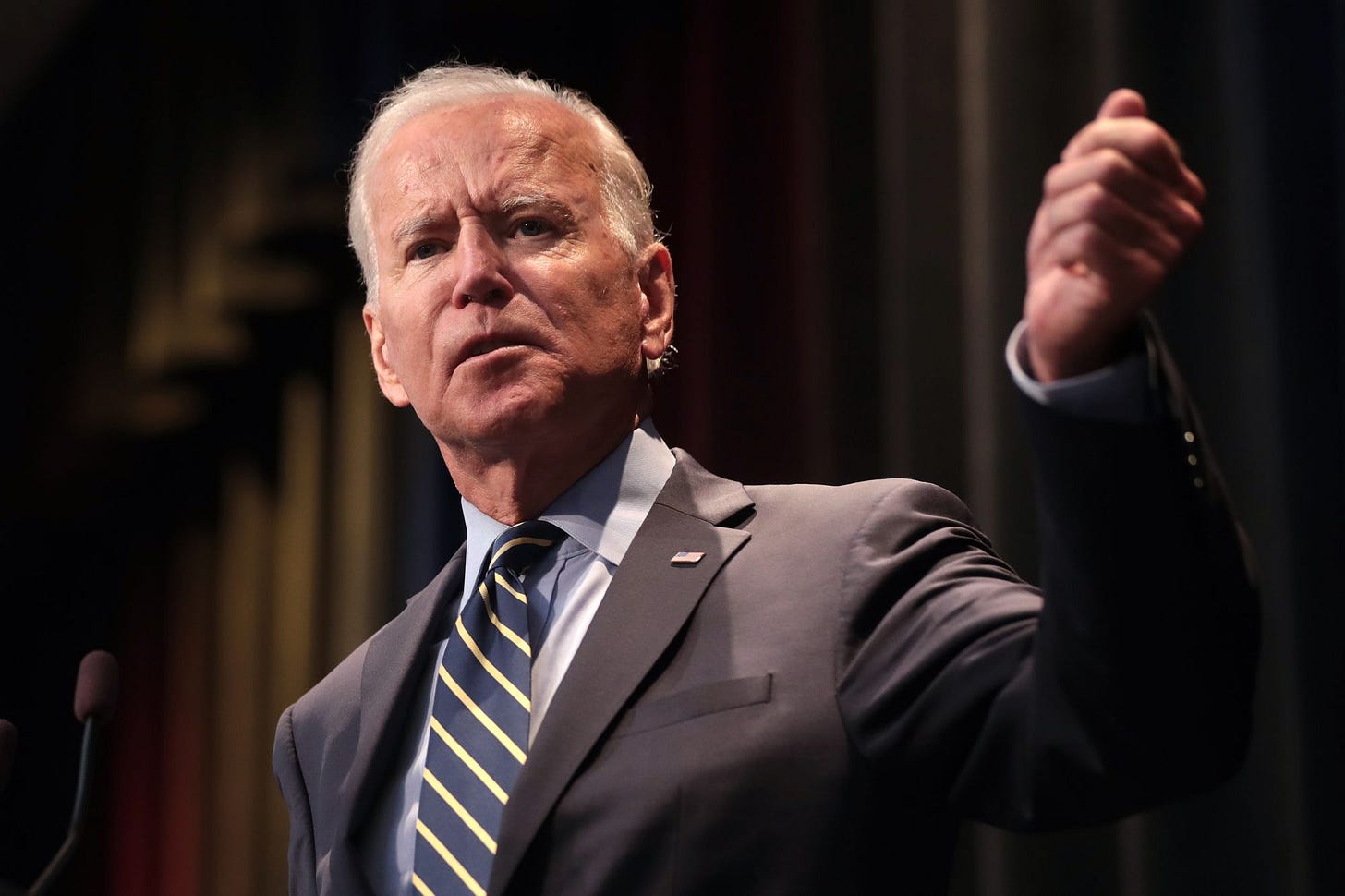

Some, like Biden and his allies, have blamed this inflation on transitory factors like continuing COVID infections or the war in Ukraine. This is a valid point—supply-side factors have made inflation worse than it would be otherwise. But excessive stimulus has also played a role.

I’d say that dollars—as measured by total spending in the economy—are about 4 percent too plentiful. People are spending about 4 percent more than you might have expected them to spend if pre-pandemic trends continued.

David Beckworth, using excess nominal GDP over expectations, finds we were about 3 percent too hot in the fourth quarter, and likely will find more in 2022.

So spending didn’t just recover from pandemic lows and return to trend—a welcome development—it actually exceeded the pre-pandemic trend.

We must update our policy playbook accordingly. It’s time to put aside ideas like stimulus and job creation—they’ve served their purpose—and instead focus on ideas like productivity and efficiency. These policies will allow the real economy to continue growing while bringing inflation under control.

Unfortunately, federal policymakers have been slow to pivot. They are still boosting demand—as if employment, not inflation, were our biggest problem—and in many cases they seem actively hostile to cost control or ideas to conserve scarce labor.

Not all of our present inflation is the fault of policymakers. But they are contributing to the problem substantially. I wish they’d stop.

The Fed is far behind the curve

When inflation is high and unemployment is low, a standard macroeconomics textbook calls for us to “put on the brakes” in both monetary and fiscal policy.

But we’re putting the brakes on only slowly—if at all. Thus far, the Federal Reserve has only hiked interest rates into the 0.25-0.50 percent range. This is only one step off of the maximally expansionary federal funds rate. It’s the sort of rate you’d set if you thought you still had far too little demand. This lowers the cost of borrowing, giving consumers the ability to spend more on things like houses and cars, or businesses the ability to invest more. Rates today are the same as the rates we set in the final months of 2008, when we were desperate to stop a total economic shutdown.

But our economy doesn’t look like the final months of 2008. Our recovery in the job market is close to late 2019 levels of employment. And the economy looks like it’s running even hotter than that if you go by wage hikes or inflation. In late 2019 we had a federal funds rate of 1.50 to 1.75 percent—about 1.25 percent higher than what we currently have.

There’s another more subtle effect here, beyond the nominal rates. Since the Fed is already behind the curve on expected inflation (as we mentioned above, markets now expect 3 percent over the next ten years) the real interest rates the Fed is setting or expecting are actually lower—and therefore, more expansionary—than a look at nominal rates only might suggest.

While low interest rates can be helpful in creating a labor market recovery, that mission is mostly complete. The Fed should be pivoting to curbing excess demand. The Fed is likely to raise interest rates by another 50 basis points in May, but this slow, deliberate pace—like turning a battleship in the open sea—is ill-suited for the fast-changing environment.

The Federal Reserve could—right now—easily intellectually justify a federal funds rate of 2 or 3 percent, and perhaps more. Time to get there sooner rather than later.

Biden is still trying to sneak in more stimulus

President Joe Biden seems to be operating in much the same way. Though a macroeconomics textbook would call for policies that reduce the short-run deficit, Biden keeps pushing for policies that would raise it, releasing more money into the economy, even as money is already too plentiful. While his American Rescue Plan was a defensible choice—to avoid a slow recovery like that of the 2010s and heat up the economy quickly—it is far less defensible to continue trying to add to near-term deficits after the rescue plan proved itself more than sufficient.

Consider, for example, that Biden spent November trying to hoodwink Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV) into a frontloaded version of the Build Back Better bill, even though Manchin had explicitly rejected frontloading. Such a frontloaded bill would have released even more fiscal stimulus into the already cash-flush 2022 economy. Or consider that Biden continues to extend the emergency student loan pause, forgoing a chance to withdraw money from the overheating economy.

These fiscal policies aren’t huge. The Penn Wharton Budget Model, for example, estimated Build Back Better would add about 0.2 points to inflation. Student loans are maybe another tenth of a percent beyond that. But these policies are directionally wrong on the demand side. Faced with inflation sixty tenths of a percent above the norm, you should be actively looking for ways to reduce it—not fighting a powerful and skeptical Senator for the right to add another two tenths beyond that.

In the 2022 State of the Union address, Biden promised to fight inflation, but he did so in part by advocating more spending. For example, he would fight childcare costs at the family level by subsidizing them, or by paying for free pre-K. While these plans would make the specific item cheaper out-of-pocket to families, they would release even more money into the economy and allow people to bid up other items with their savings. Sure, this inflationary impact could be offset (or more than offset) by tax increases, but headlining your inflation-reduction paragraph with inflation-increasing provisions doesn’t really inspire confidence in your commitment to the cause.

Labor is scarce. Time to act like it.

80 percent of working-age Americans hold a job, which is close to 2019 levels, and close to all-time highs.

There’s potentially some more job creation to be done. The U.S. has exceeded 81 percent before, and it should do so again. And as our friend Joseph Politano points out, experience of other developed countries suggests the low-to-mid-80s might be possible.

But much of the economic growth for the rest of the Biden administration will have to come from deploying the labor we have more efficiently. Unfortunately, the Biden administration is showing little interest in efficiency.

For example, one way of increasing efficiency is to deploy your scarce labor force in the industries where your country’s comparative advantage is greatest, and then trade for the rest. But once again, in his State of the Union address, Biden takes the opposite tack. He says he will fight inflation by building more things in America.

Consistent with that goal, the administration is strengthening “Buy American” rules for federal procurement. These rules categorize goods by whether or not they have a sufficiently high domestic content of American parts—and then apply a “price preference” of up to 30 percent towards the goods that meet the domestic content threshold. In other words, it will overpay for American goods.

In a recessionary time, like 2010, this might make some sense; you could be getting American workers to work who might be unemployed otherwise. (Though broader demand-side support would be a more efficient way of accomplishing the same goal.) Future Biden White House personnel like Jared Bernstein wrote eloquently about imports under situations of low employment.

In this context, the trade deficit was subtracting from demand in the domestic economy. Spending that could have employed people who needed jobs in the U.S. was instead employing people in Germany, China, and other countries from which America imports goods and services.

It’s a valid argument—that the case for trade breaks down if you don’t put everybody to work. But right now, the American workers are already working. The manufacturing labor force is needed in sectors like automobiles and semiconductors where consumers are feeling shortages. What “Buy American” does in a hot economy is use the taxpayers’ own money to artificially outbid companies like Tesla or Intel for workers.

Similar rules are going into effect for the materials for the infrastructure package passed last year. “From Day One, every action I’ve taken to rebuild our economy has been guided by one principle: Made in America,” Biden said earlier this month. But there’s only so many American workers to go around, and their employment is touching historic highs already. It’s time to start thinking about where their output is most needed, not just assigning them to every single task possible.

“Subtracting from demand in the domestic economy” with imports, as Bernstein described, is in fact exactly what the economy needs right now. But it seems like the administration can’t or won’t pivot. Perhaps you get your reputation as a “create jobs” guy or a “buy American” guy, and you build an identity and a political career around that, and you’re stuck with that even after it no longer makes sense.

Another way of increasing efficiency is to get our existing work done with fewer hours of labor. For example, I’ve written previously about our difficulties building anything quickly. It often comes down to paperwork requirements and legal fees from the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). Contrary to what you might expect from its name, NEPA doesn’t substantively protect the environment with any specific rules, it just requires the government to do hundreds or thousands of pages of cost-benefit analysis for every permitted project, and it allows just about anyone to sue the government if the analysis isn’t sufficiently exhaustive. It’s a tremendous waste of resources, especially on the many projects that clearly pass a cost-benefit test already.

The Trump administration noted that these statements were taking an average of 4.5 years and 575 pages to complete, and attempted to make this process a less labor-intensive (perhaps a 515-page analysis could be almost as informative!) freeing up valuable knowledge workers to other parts of the economy.

Biden began reversing these changes on day one of his administration, and is now finalizing that reversal. Now, there were some components of the Trump proposal that obviously wouldn’t fly in a Biden administration—like limiting the ability to consider climate change impacts—but the administration is also eagerly going back to requiring agencies to consider effects that are “products of a lengthy causal chain” or “remote” in geography or time.

If agencies just gave their best shot at considering indirect effects, and then made their decisions, this would probably be fine. But the problem is that project opponents are allowed to sue, even in bad faith, and the more remote causal chains you require agencies to consider, the more the agencies can be sued.

Despite the success of Biden’s vigorous full-employment agenda, which has made labor scarce, Biden is treating labor as something cheap and plentiful that can be used freely on things like uncompetitive government contracting bids or defending the government’s own decisions from insincere nuisance lawsuits. The more labor goes to these inefficient uses, the less labor is available to create a competitive market in consumer goods and bring prices back down.

A recent Gallup poll found that inflation is the most important problem facing the country today, according to 17% of voters; it’s the most popular answer, and its popularity has almost tripled in five months. On neither the demand side nor the supply side is the Biden administration making a concerted effort to contain it.

That has to change, ideally starting now. There are, realistically, nine more months of unified Democratic governance left. And if current trends continue unabated, I’d expect only thirty-three more months in Biden’s presidency.