We just might tame inflation without causing a recession

Inflation is falling while the unemployment rate stays very low.

In recent weeks, the Bureau of Labor Statistics has made a series of announcements that have made me more optimistic about America’s economic prospects in 2023. On January 6, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reported that the economy added a healthy 223,000 jobs in December, while the unemployment rate declined slightly to 3.5 percent.

A week later, the BLS announced that prices actually fell slightly between November and December. The annual inflation rate for December was 6.5 percent, the lowest it’s been since October 2021.

Then on Wednesday, we learned that the situation is similar for the producer price index, which measures costs faced by businesses. It fell a surprisingly large 0.5 percent between November and December, while the annual inflation rate for producers was 6.2 percent. And on Thursday, the Labor Department announced that there were 190,000 new unemployment claims filed last week—the lowest number of new claims in several months.

In short, we’re seeing two salutary trends at the same time: inflation is coming down, while the job market continues to boom.

This wasn’t supposed to happen. When the Fed began raising rates last March—and especially after the Fed started raising rates in large 0.75 percent increments in June—a lot of economists assumed that this would push the US economy into a recession. By August, even Fed Chair Jerome Powell seemed to be expecting the worst. In a widely-discussed speech, he warned that the Fed’s rate hikes were likely to lead to “slower growth” and “softer labor market conditions,” and bring “pain to households and businesses.”

He didn’t use the word “recession,” but everyone knew what he meant.

But it’s starting to look like inflation might come back down without a recession or significant job losses. Last month’s 223,000-job gain was the smallest in two years, but it was still above the roughly 200,000 new jobs we need each month to keep pace with population growth. And today’s unemployment rate of 3.5 percent is as low as it’s been at any point since 1969.

It’s too early for Powell to take a victory lap. The inflation situation is fluid, and the inflation rate could start to creep back up in the coming months. But it now looks like there’s a real possibility that the recession everyone was dreading in 2023 won’t happen. We might get an “immaculate disinflation” instead.

A complex inflation picture

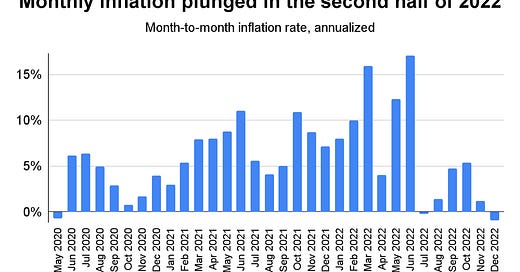

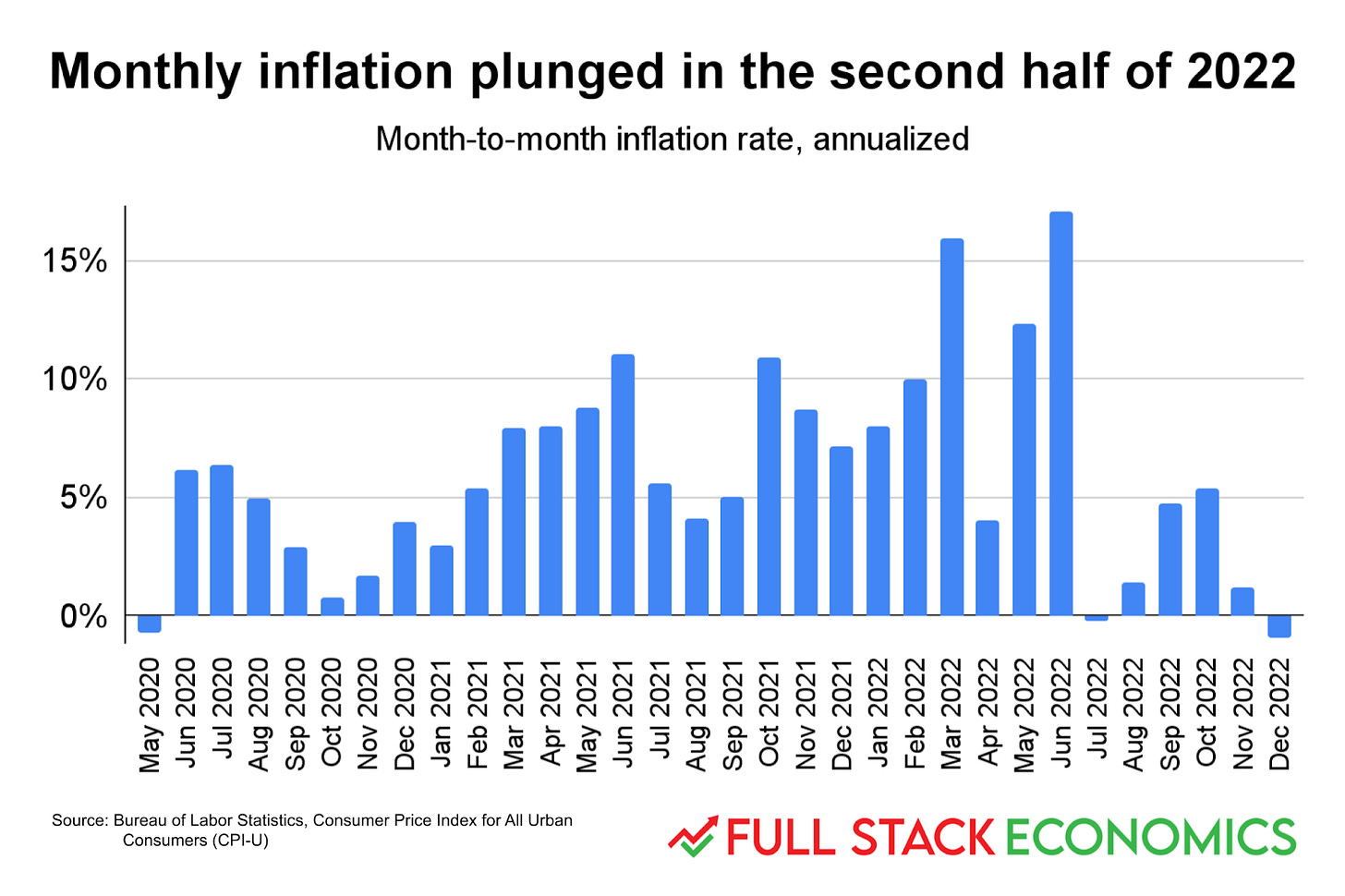

You might object that the annual inflation rate is 6.5 percent—that is, prices in December 2022 were 6.5 percent higher than in December 2021. That’s obviously much higher than the Fed’s 2 percent target. However, this is a case where the annual inflation figure is misleading.

You might remember back in August when Joe Biden said there had been no monthly inflation in July, and people made fun of him for it. His claim was technically accurate—prices in July 2022 were actually slightly lower than they’d been in June—but it was misleading because the month-to-month inflation readings for June, May, and March had been scorchers.

The situation now is quite different. Once again, prices fell slightly between November and December. The difference is that this came after several other months of low or negative inflation. Indeed, the annualized inflation rate between June and December of 2022 was just 1.9 percent. If the next six months are like the last six months, the Fed will achieve its 2 percent inflation target.

The big question, of course, is whether we should expect the next six months to look like the last six months.

And the honest answer is we don’t know. There have been several different factors pushing the inflation rate in opposite directions, and we can’t be sure how they’ll net out in the coming months. But there is some reason for optimism.

The low inflation of the last six months is mostly the result of rapidly falling gas prices. Over the last six months, the annualized “core” inflation rate (which excludes food and energy) was 4.6 percent. If gas prices stop falling and core inflation stays at its current level, then headline inflation will come in significantly above the Fed’s 2 percent target.

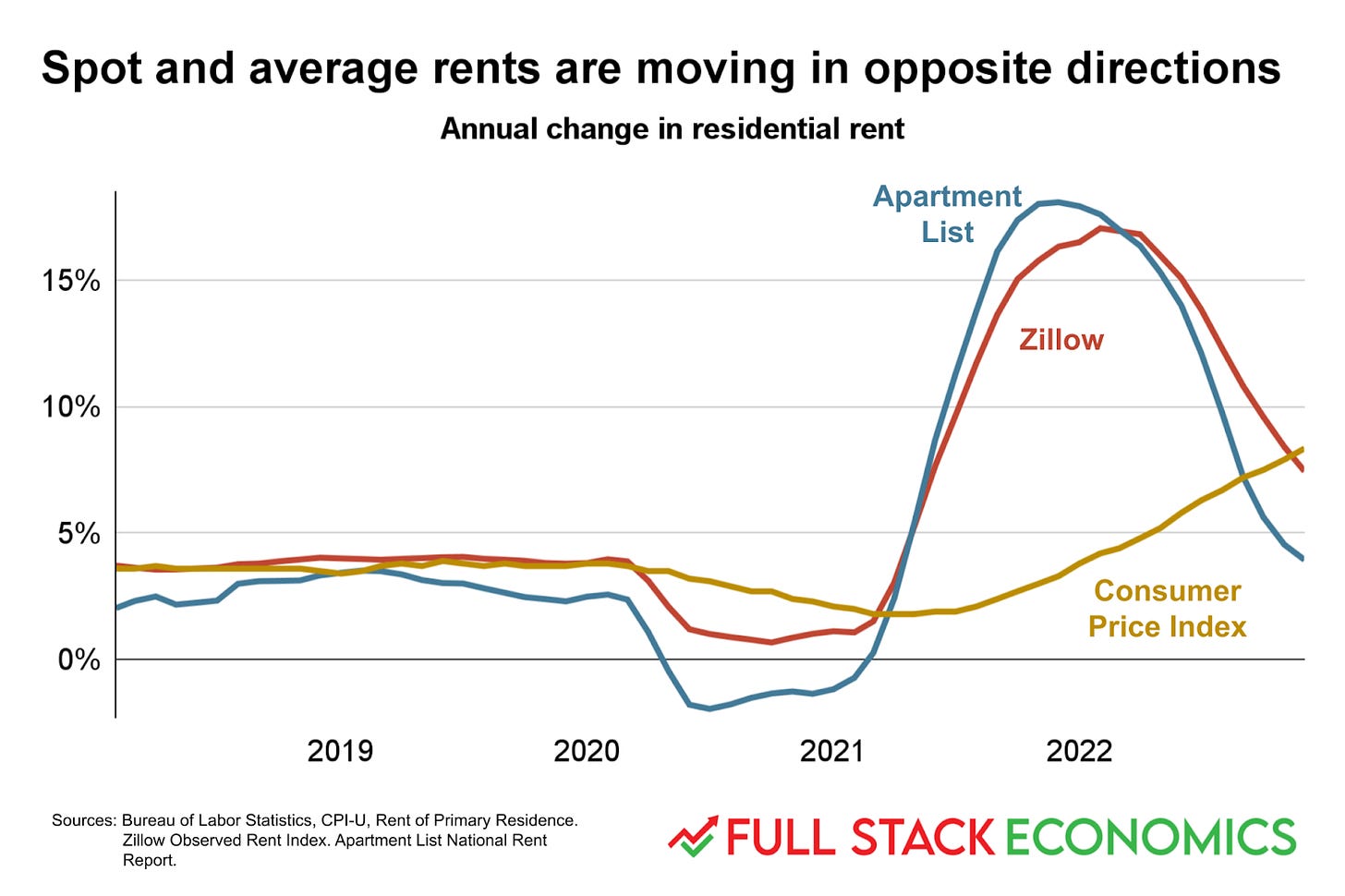

On the other hand, one of the biggest components of core inflation is shelter, and shelter inflation has been high and rising in recent months. But as longtime readers know, the CPI’s shelter component lags behind “spot rents” (the rent a new tenant would pay if they signed a lease tomorrow) by about 12 months. And the rate of inflation for spot rents (the red and blue lines in the chart above) peaked about a year ago. This means that we should see shelter inflation rate, as measured by the CPI, peak in the coming months.

And so this means that while the Fed hasn’t fully accomplished its inflation-fighting goals, it looks like the end may be in sight. We can expect headline inflation to stay well above 2 percent for the first few months of 2023, due in part to high shelter inflation. But later in the year, shelter inflation is very likely to decline. If we don’t suffer any more pandemics or geopolitical crises, it’s easy to imagine headline inflation getting close to the Fed’s 2 percent target by the end of 2023.

And while it’s too early to say for sure, it’s looking increasingly likely that we’ll get there without large-scale job losses.

Why haven’t we had a recession yet? Again, nobody knows. People have been extrapolating from the Great Inflation of the 1970s. Between 1979 and 1981, Fed chair Paul Volcker jacked up interest rates to tame inflation, triggering a severe recession in the process. Many economists have naturally assumed that Powell’s aggressive rate hikes would have a similar impact.

But the situation today is not the same as the 1970s. We’ve only had a couple of years of high inflation, compared to the nearly decade-long experience of inflation in the 1970s. Maybe there hasn’t been enough time for inflation expectations to become entrenched the way they were back then.

Or maybe modern economies are just less inflation-prone than the economies of the 1970s. Japan has spent the last 30 years mostly battling deflation, and there’s reason to think Western democracies have become more like Japan over time, with an aging and slow-growing population. Maybe one consequence of this is that it’s relatively easy to bring inflation back under control.

Or maybe celebration is premature and we actually are on the verge of a severe recession. But so far I’m not seeing signs of it.

Nice job. I was beginning to think I was the only one who saw how low inflation was in the second half. Now there are two of us - that's almost viral.

My piece explains why I do not believe inflation will just spontaneously creep up in the next six months. On the contrary, the lagged rent data go from crazy to gradaually helpful and energy almost surely goes negative because oil was so high early 2022.

https://www.cato.org/blog/inflation-fell-19-second-half-2022-107-first-1