These companies are eager to lend you money to shop online

Buy Now Pay Later companies offer credit to entice you to shop more.

If you’ve been shopping online lately, you may have seen a prominently-listed option under the sticker price, provided by a company called Affirm. For example, for a high-end outdoor grill listed at Williams Sonoma, the price is $1499.95, but directly under that price is the text “as low as $136/month or 0% APR with Affirm.” You can pay $499.98 over three months (zero interest), or $135.51 over twelve months (resulting in $126.11 of interest payments—an effective rate of 15.17%).

Affirm is a leader in the emerging “Buy now, pay later” industry (competitors include Klarna and Afterpay) and has been on a tear lately, leveraging its early success with Peloton and inking big deals with Walmart and Amazon. Its share price has doubled since the summer, giving it a valuation of more than $30 billion.

Obviously the core idea here is not new; consumers have long broken up payments into smaller chunks, in everything from auto loans to credit cards to layaway. But the current crop of Buy Now Pay Later companies are well-tailored to online commerce.

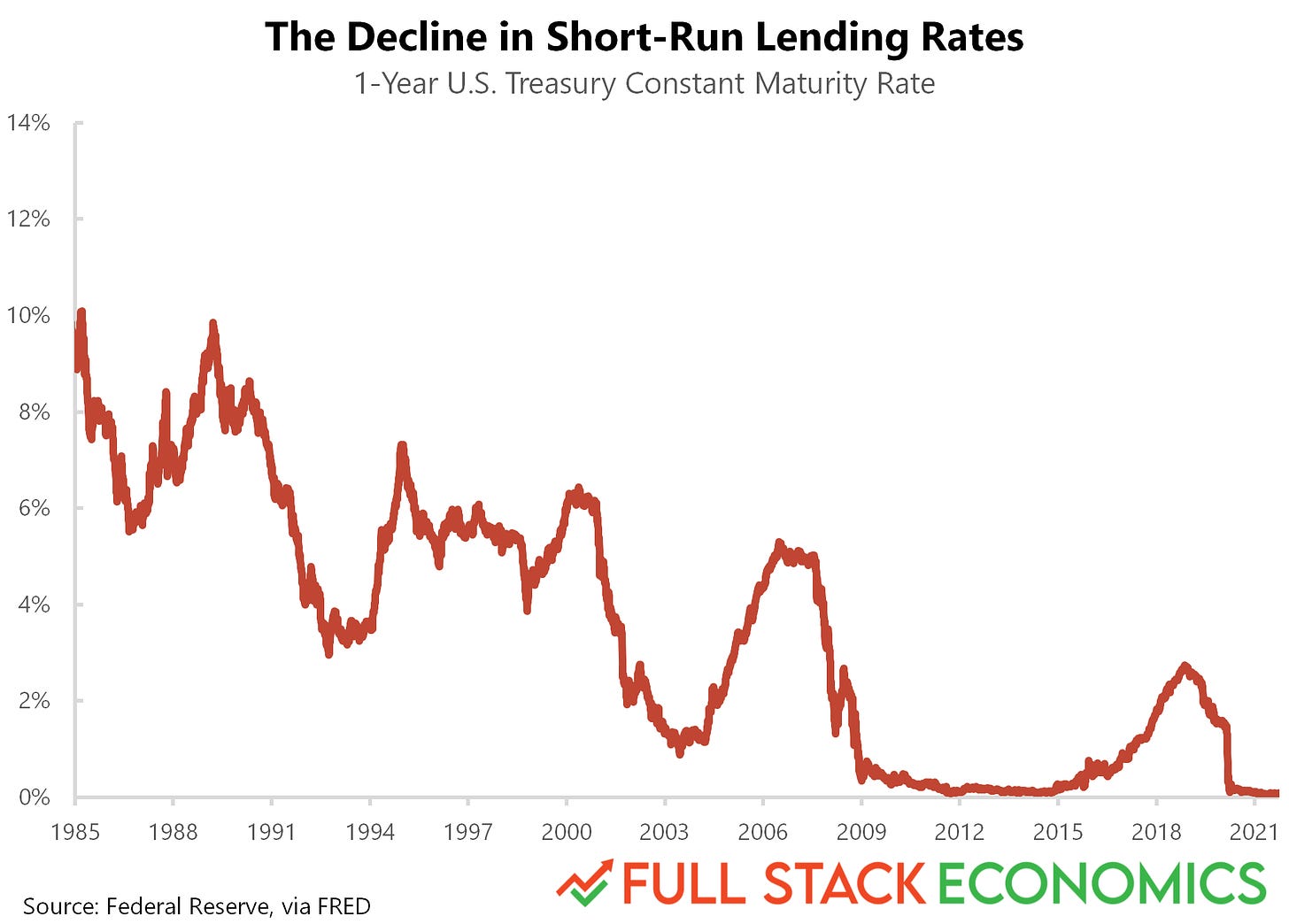

The BNPL boom is also driven by our low-interest rate environment, which is likely to remain with us for quite some time. There is a massive and growing global demographic of late-middle-age savers looking for people to lend to. Their hoards of savings need places to go and earn a return, and traditional markets are pretty saturated. BNPL extends lending to some new markets that previously might have gone untapped.

Softening the pain points

A key objective for BNPL firms is to make checkout as painless as possible. Online stores can see that the vast majority of their customers browse without buying. Even many of those that load items into their cart frequently abandon their orders. Merchants become understandably obsessed with making it even slightly easier for a customer to close the deal. This is advertised prominently on Affirm’s page for merchants: “flexible payments that help shoppers say yes.”

BNPL is really two businesses rolled into one. First, it helps merchants by making their customers more likely to complete purchases, and it even can drive traffic to the merchants through its own proprietary portal or app. In exchange, it charges merchants a fee. Second, for its longer-duration payment plans, it extends credit to higher-risk customers and attempts to earn interest income, providing a second stream of revenue. Affirm divides its income statement into these two major categories: revenues from merchant fees and its virtual visa cards in the first category, and interest income in the other.

Checking out with the BNPL method barely seems more difficult than paying with a traditional card saved in your browser. A company like Affirm uses only a “soft pull” to check credit, and it builds a relationship with customers across multiple stores, making it easy to immediately qualify for a BNPL deal.

BNPL firms also try to reach people who might not have access to traditional credit cards or lending, bringing in new customers.

The 0% APR loans are also an enticement, with a longer interest-free break than if they had used a traditional credit card. In fact, 38% of Affirm’s transactions were like this, according to its most recent earnings presentation. Finally, BNPL companies are experimenting with apps or portals where you can shop for items directly; 29% of Affirm’s transaction volume comes through this route.

In other words, these companies are efficient funnels for e-commerce, and it makes sense that even giants like Amazon and Walmart are eager to partner with them.

People are very willing to lend money

If you’re the kind of person who gets antsy about debt, reading about this probably makes your hair stand on end. You might think that everyone—neighbors, businesses, and government—should be financing most transactions with cash and avoid taking on a lot of debt.

The problem with this is that when it comes to bonds or cash, one person’s asset is another person’s liability. And right now, there’s a large global cohort of wealthy people in late-middle-age who are anxious to accumulate large reserves of liquid assets in preparation for retirement.

They can invest in stocks or real estate, and many do, but those assets have high prices and uncertain returns. Typically, financial advisors tell them to put a substantial portion of their portfolio in fixed-income investments.

For these people to have low-risk assets, other people need to borrow. And while the federal government has been borrowing a lot, it still hasn’t borrowed enough to satisfy the Boomers’ appetite for safe assets. So Boomers are driving interest rates downward.

This means that Affirm’s “working capital”—the money or inventory locked up for the short-run in revenue-generating activities—is very cheap. This runs contrary to what is typically taught in business schools. For many businesses, in other industries or at other times in history, a high level of working capital would be a bad thing. When short-run interest rates are high, it’s a bad thing to “lock up” money by letting a customer pay later. But the lower interest rates get, the easier it gets to make a business like Affirm profitable.

The low-risk, short-term, zero-interest business is always going to lose money on the lending, but it doesn’t lose very much, and it earns merchant fees. Is there a chance that someone signs up for a 3-month payment plan and then defaults on it? Sure. But it doesn’t seem likely to happen that often. And if you do take a loss on a small payment plan with someone, you’ve learned something about their creditworthiness and you can stop offering deals to them in the future.

The longer payment plans are far more likely to have defaults, but they are priced with higher interest rates to compensate for that risk. As long as only a small percentage of these plans are delinquent at any given time, the companies make money on net.

Of course, this is a substantial caveat. A lending strategy like this is often like “picking up nickels in front of a steamroller.” In most years, it looks like easy money. But when personal income falls—as it did in 2007-2008—lenders to marginal borrowers can go broke.

Those 2007-2008 troubles are most associated with mortgages, but they also affected more diversified lenders like HSBC Finance, and they did so relatively early. The HSBC Finance consumer lending portfolio was eventually shut down, as personal incomes fell and consumers were no longer able to service their debts.

But a well-run “nickels and steamroller” strategy makes more money than it loses over the long run. And if macroeconomic stabilization policy is sound, the steamroller comes relatively rarely.

If you enjoyed this post and want to support our continued growth, please consider sharing it on social media, or leave us a recommendation in the comments on other industries to cover.