Oil prices have soared in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. That’s going to cause pain at the pump for many Americans. But the larger worry is that skyrocketing oil prices could lead to a recession.

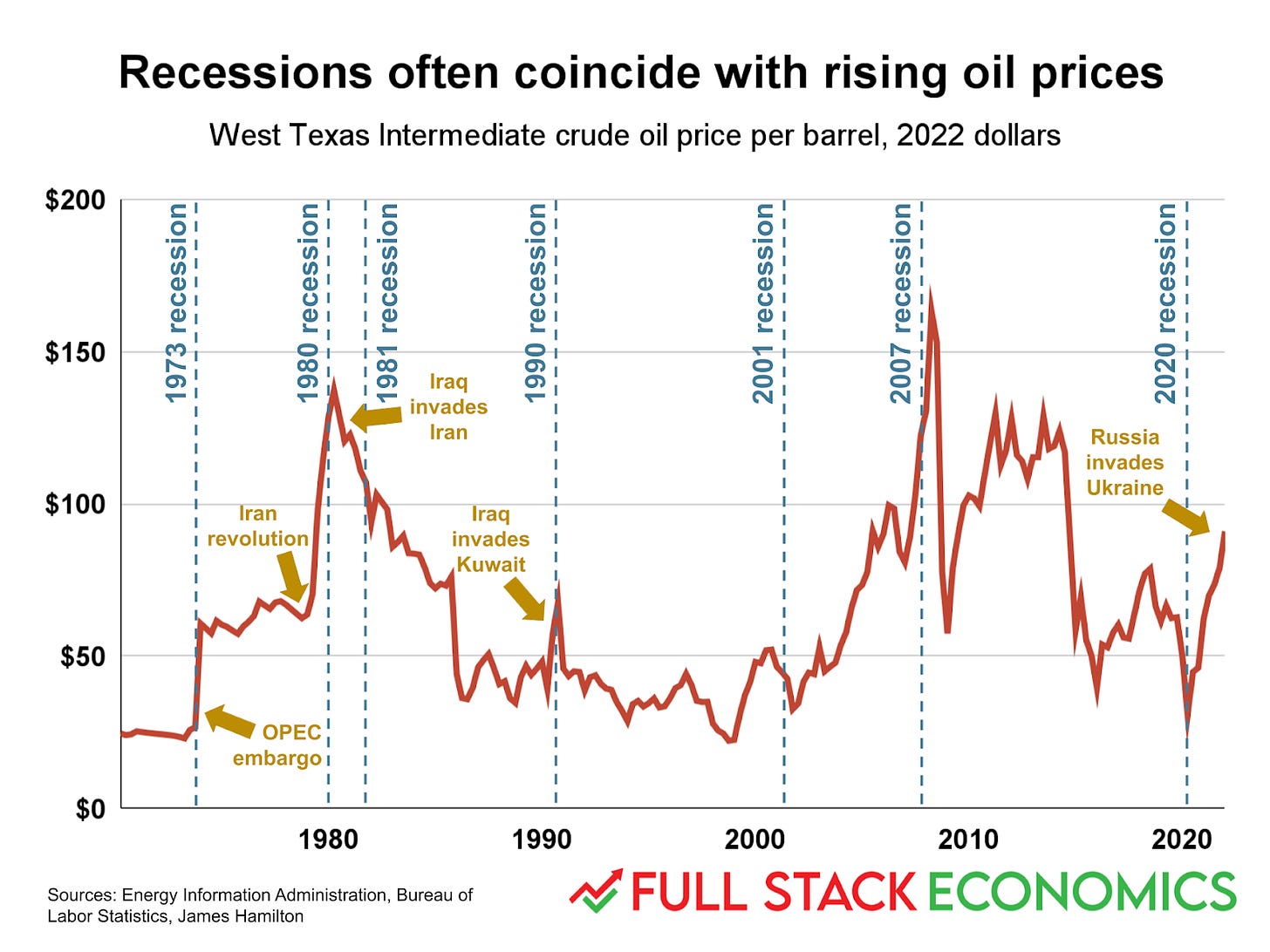

The US has had seven recessions in the last 50 years. Four of these—in 1973, 1980, 1981, and 1990—were preceded by conflicts in the Middle East that disrupted oil supplies and drove up oil prices. Two others—in 2001 and 2007—followed oil price increases driven by strong demand rather than supply disruptions.

Will history repeat itself? With war raging in Ukraine, oil prices are nearly twice as high as they were a year ago. And that’s making some economists nervous.

The Federal Reserve already had a tricky situation on its hands. As I wrote in December, the Fed was trying to bring down inflation without tipping the economy into a recession. Since then, inflation has only risen more. On Thursday, the Bureau of Labor Statistics announced that the annual inflation rate was 7.9 percent, the highest it’s been in 40 years.

The attack on Ukraine—and the resulting surge in the prices of oil, natural gas, and other commodities—is likely to push prices up even further in the coming months. And that puts the Fed, which holds a regularly-scheduled meeting this week, in a difficult position.

“Prior to the Ukraine war, it was already going to be difficult to execute a soft landing,” said David Beckworth, an economist at the Mercatus Center. The war in Ukraine “complicates matters a lot.”

“Energy independence” doesn’t protect consumers

Russia is the world’s third-largest oil producer (after the United States and Saudi Arabia) and the second largest crude oil exporter (after Saudi Arabia). The war between Russia and Ukraine—and the resulting sanctions against Russia—are expected to disrupt the Russian oil industry at a time when oil supplies are already tight. So it’s little surprise that oil prices shot up in the days after Russia invaded Ukraine.

Republicans have tried to pin blame for high oil prices on President Joe Biden. They point out that he campaigned on transitioning away from fossil fuels during the 2020 presidential campaign, and that he has blocked some energy-related projects in the United States.

However, it takes years for a new energy project to come online. Today’s oil supply largely reflects decisions made before Joe Biden took office. Some of Biden’s policies will make it harder to bring down oil prices over the next couple of years, and that could expose him to legitimate criticism if oil is still expensive in 2024. But he just hasn’t been in office long enough for these decisions to affect the short-term price of oil.

The Republican criticisms also ignore the global nature of the oil market. For decades, politicians have talked about the need for the United States to achieve “energy independence.” The idea is that if we produce enough energy domestically for our own needs, we’ll be insulated from the volatility of overseas oil markets.

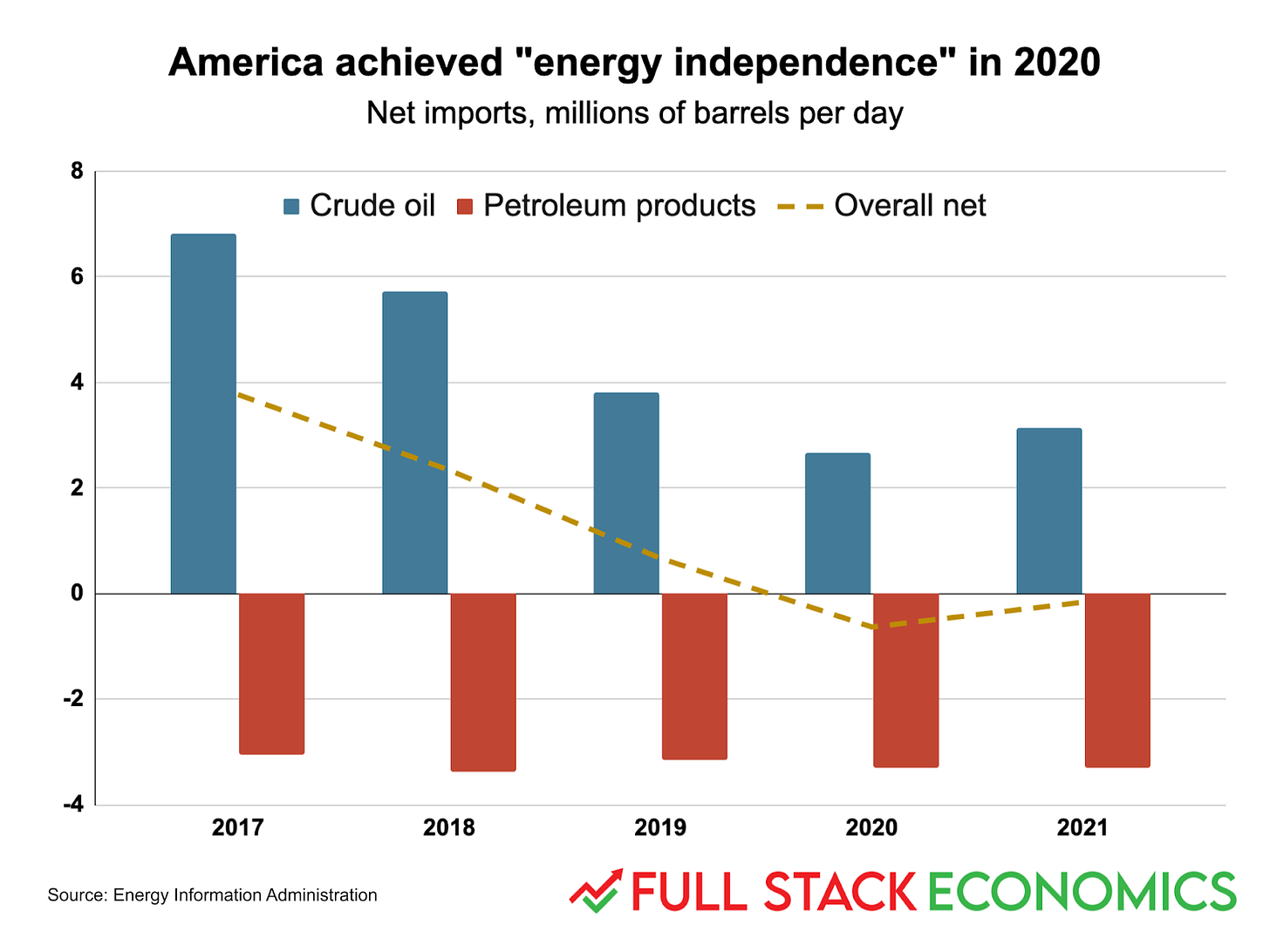

As this chart shows, the US actually became a net petroleum exporter back in 2020—arguably achieving “energy independence.” The US still imports a few million barrels of crude oil every day, but then we refine some of that oil and sell it back to foreigners. When you net these figures out, the US already produces enough fossil fuels to meet our domestic needs.

But this hasn’t insulated consumers from rising energy prices. Producers—including US oil companies—can put oil on a tanker and ship it anywhere on the planet. As a result, oil prices tend to be fairly uniform around the world. That means American consumers are competing with consumers in Japan and Brazil for gas. If they’re paying higher prices, we will be too.

The global nature of the oil market also limits the practical impact of Joe Biden’s decision last week to ban imports of Russian oil. European nations import a lot more Russian oil than the United States, and many are too dependent on Russian oil to immediately follow America’s lead. European nations say they want to phase out Russian energy imports, but they expect to do it over a period of years. Until that happens, the US import ban won’t have much impact on the price at the pump. The US ban will just shift trade patterns, with more non-Russian oil flowing to the US and Russian oil flowing elsewhere.

Other sanctions may have a bigger impact. Western companies like Shell and BP have been pulling out of Russia, which could starve the Russian oil industry of capital and expertise. Sanctions may also make it difficult for Russian oil producers to get the equipment and services they need.

Oil shocks and recessions are often linked

As the economist James Hamilton has documented, there seems to be a strong connection between rising oil prices and recessions:

In October 1973, a coalition of Arab states declared war on Israel. When the US took Israel’s side, Arab states retaliated by declaring an oil embargo. Oil prices soared, and the US officially fell into recession in November 1973.

In February 1979, the Iranian Revolution disrupted the supply of oil. Over the course of 1979, oil prices doubled from their already high level at the start of the year. A recession started in the US in January 1980.

In September 1980, Iraq attacked Iran, hoping to capitalize on the chaos that followed the Iranian Revolution. Oil prices didn’t rise further—they were already near record highs—but they stayed unusually high. The US fell into another recession in July 1981.

On August 2, 1990, Iraq invaded Kuwait. Oil prices jumped in response. US economic output peaked in July 1990, then the US fell into a recession that lasted until March 1991.

After reaching a 20-year low in December 1998, oil prices nearly tripled by November 2000 (this seems to have been due to strong demand, not supply disruptions). A recession started in March 2001.

Oil prices soared from $54 per barrel in January 2007 to $94 per barrel in November 2007—and to $133 in June 2008 (again, this seems to have been demand-related). The Great Recession officially started in December 2007.

The COVID recession that began in February 2020 could be seen as the exception that proves the rule. There was no significant increase in oil prices in the preceding years.

Correlation doesn’t prove causation, of course, but there’s reason to suspect that this pattern is more than a coincidence. Notice, for example, that the most severe recessions of the last 50 years—in 2008 and the double-dip recessions in the early 1980s—followed the biggest price spikes of the last 50 years. The smaller oil price jumps in 1990 and 2000 were followed by mild recessions.

One interpretation is that high oil prices directly cause recessions. Perhaps the extra costs of energy imports force firms to lay off workers and cut output. Or maybe consumers respond to rising gas prices—and the fear of further increases in the future—by cutting spending in other categories.

But economists have also suggested a more subtle explanation: central banks tend to overreact to oil supply shocks, tightening monetary policy too much and thereby triggering a recession.

The Fed might want to tolerate more inflation in 2022

Inflation is caused by too much money chasing too few goods. Economists distinguish between two ways this can happen. When there’s an excess of dollars, that’s called demand-side inflation. When there’s a shortage of goods, that’s called supply-side inflation.

David Beckwroth, the Mercatus economist, argues that this difference is important for monetary policy.

If inflation is being caused by an excess of demand, then it needs to be addressed by tighter monetary policy (higher interest rates) or fiscal policy (smaller deficits). Otherwise, demand is likely to keep rising and inflation could rage out of control. Demand-side inflation is usually a side effect of a booming economy, so tapping the brakes won’t necessarily cause much harm.

On the other hand, if inflation is caused by supply-side problems—say, a fire at a key computer chip factory or a war that disrupts the flow of oil—then policymakers might want to sit tight. Supply-side problems tend to be self-correcting. Either the war in Ukraine will end or oil producers elsewhere in the world will step up to offset the lost Russian production.

If policymakers rein in demand too much, the economy could wind up with too little spending once supply problems are resolved. So during episodes of supply-side inflation, it often makes sense for a central bank to accept some extra inflation rather than risk throwing people out of work.

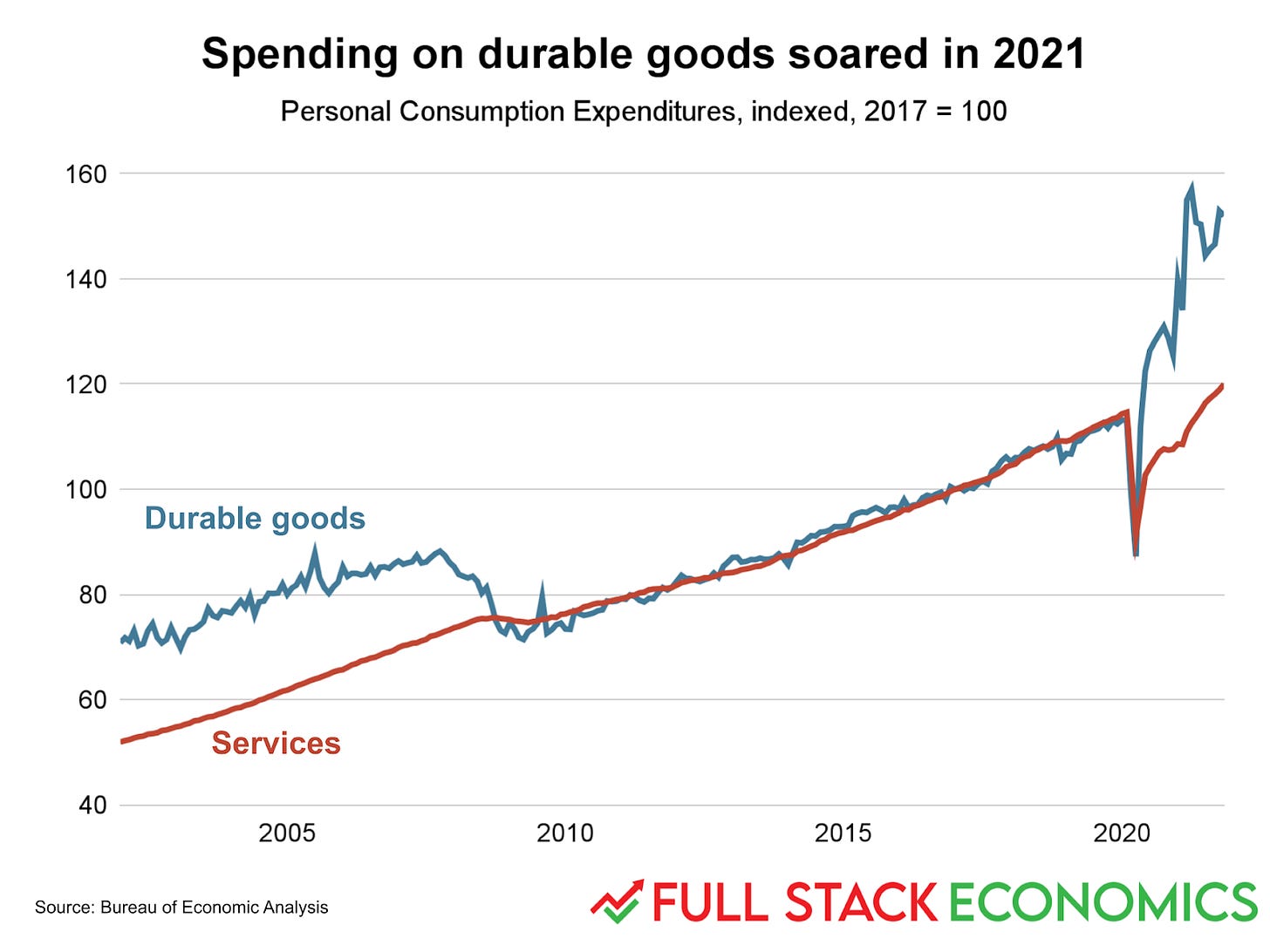

The 7 percent inflation America experienced in 2021 was at least partly a demand-side phenomenon. It’s true that semiconductor shortages and COVID-related closures created supply problems in some sectors. But there was also a ton of new money sloshing around. A series of big COVID-related spending packages put extra money in people’s pockets. That money got spent on cars, exercise bikes, and other durable goods. The Fed kept the monetary spigots wide open in 2021, leaving short-term interest rates near zero for the entire year. Inflation surged in the second half of 2021.

So at the start of 2022, it seemed clear that the Fed needed to raise interest rates enough to nudge the inflation rate back down to two percent.

But now the Ukraine conflict threatens to worsen supply-side problems and greatly complicate the Fed’s job. Tightening is still appropriate, because the Fed still needs to deal with excess demand. But Beckworth says the central bank shouldn’t necessarily target a quick return to 2 percent inflation. Gasoline prices could continue to rise. To get the overall inflation rate back down to 2 percent in that scenario, the Fed might need to engineer falling prices in other sectors of the economy. That could mean heavy job losses in those sectors.

So in Beckworth’s view, it would be better for the Fed to “look through” the portion of inflation that’s driven by oil shortages. But that’s easier said than done.

Already, many people are convinced that inflation is actually far above the official 7.9 percent inflation rate. A big reason for this is that the most conspicuous prices—for gasoline and food—have been rising faster than other categories.

“The Fed is going to be under a lot of pressure” to tighten monetary policy, Beckworth told me. The higher inflation gets—and the more expensive gas causes people to overestimate the true inflation rate—the more pressure the central bank will face to raise interest rates.

And this same dynamic may be why rising oil prices have so often been followed by recessions in the past: maybe rising oil prices pushed up the headline inflation figure, which created pressure on central banks to tighten and led to too much tightening.

Beckworth points to a 1997 Brookings Institution paper co-authored by Ben Bernanke, who later became chairman of the Federal Reserve.

“They showed that it's not the oil shock itself, it's the Fed's response to the oil shock that caused the recessions,” Beckworth told me. “The Fed tends to overreact when there's an oil price shock.”

Instead of targeting 2 percent inflation, Beckworth argues that the Fed should try to keep nominal spending—the total number of dollars spent in the economy—growing at a steady rate. That may mean tolerating inflation well above 2 percent for the next year or two. But it should be enough tightening to prevent inflation from spiraling out of control. And once oil prices stabilize, the overall inflation rate should return to the Fed’s 2 percent target.