The tight labor market is an opportunity for low-wage workers

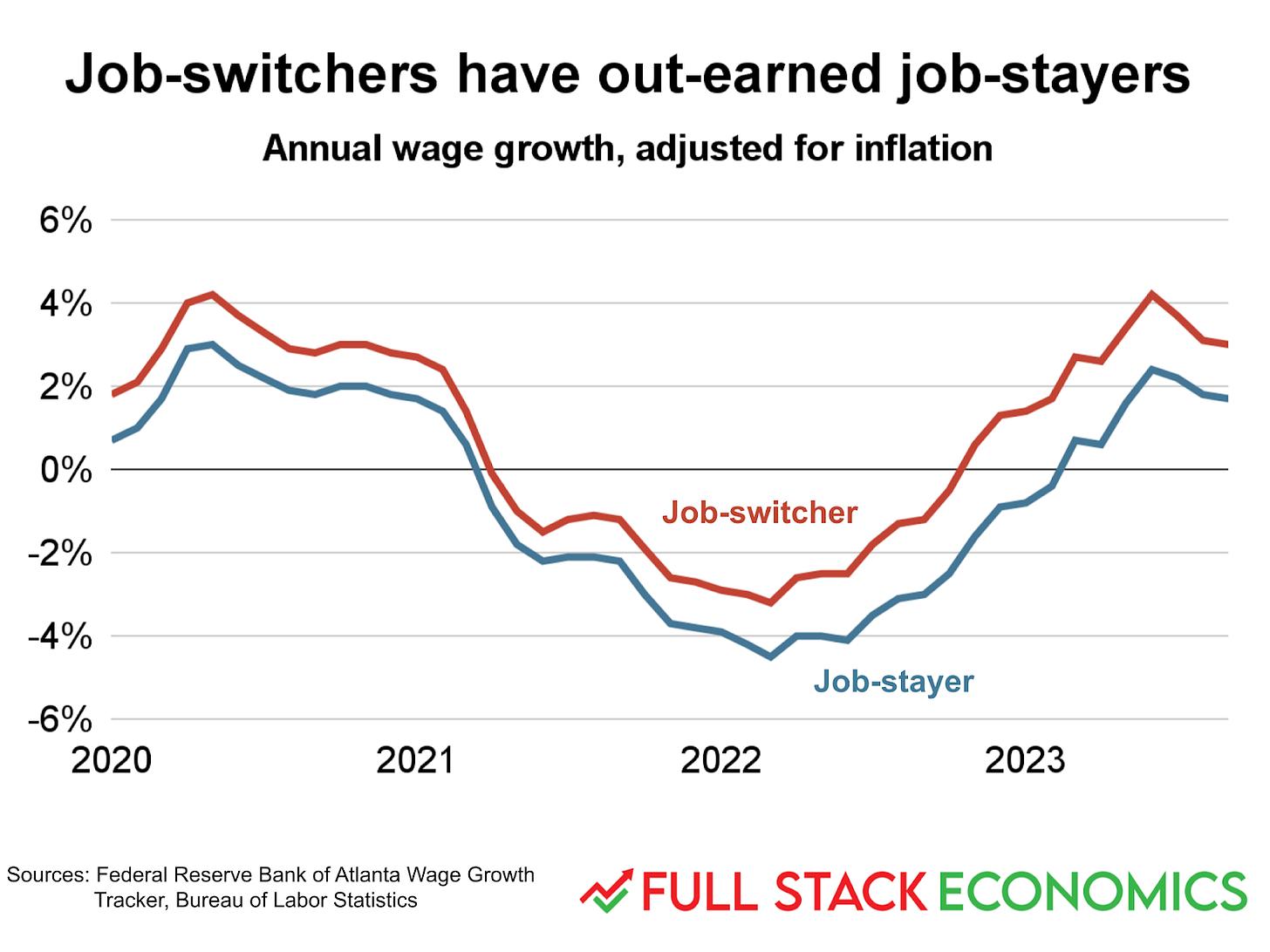

Workers who switch jobs are seeing the biggest income gains.

In August, UPS announced that driver compensation will increase to an astounding $170,000 over the next few years following hard-fought union negotiations. And, earlier this year, Home Depot said it would spend $1 billion to increase its starting wage, likely in response to Walmart’s decision to also bump up its starting salaries.

Across the economy, low-wage workers seem to be winning historic gains.

At the same time, Gallup polling indicates that nearly half of consumers view current economic conditions as poor and are about as pessimistic as they were in mid-2009, when unemployment was more than double what it is today.

So what’s going on?

A series of economic shocks—including COVID, pandemic-related stimulus spending, the war in Ukraine, and rising interest rates—have buffeted the economy over the last three years, throwing supply and demand out of balance in many industries.

Nick Bunker, an economist at Indeed Hiring Lab, told me that sectors were differentially affected by these shocks. Some industries engaged in massive layoffs, while others couldn’t get enough labor. Many occupations expanded but some have contracted sharply.

This volatility has created an opening for adventurous workers to boost their earnings by moving into growing industries, Bunker said. But some more risk-averse workers have gotten trapped in jobs with declining real wages.

The practical upshot for workers—especially lower-income workers—is that now is the time to seize the initiative. If you’re in a booming industry, you should ask your boss for a raise—and look for a new job if you don’t get it. If your industry isn’t booming, you should consider switching to one that is.

It’s also a great time to move up the career ladder. Some companies have gotten desperate enough to drop degree requirements for some jobs. Others are offering extra training or career development opportunities to workers looking to switch careers. So now may be a great time to win a promotion or break into a higher-paying occupation—and lock in higher wages for the long term.

The unexpected compression

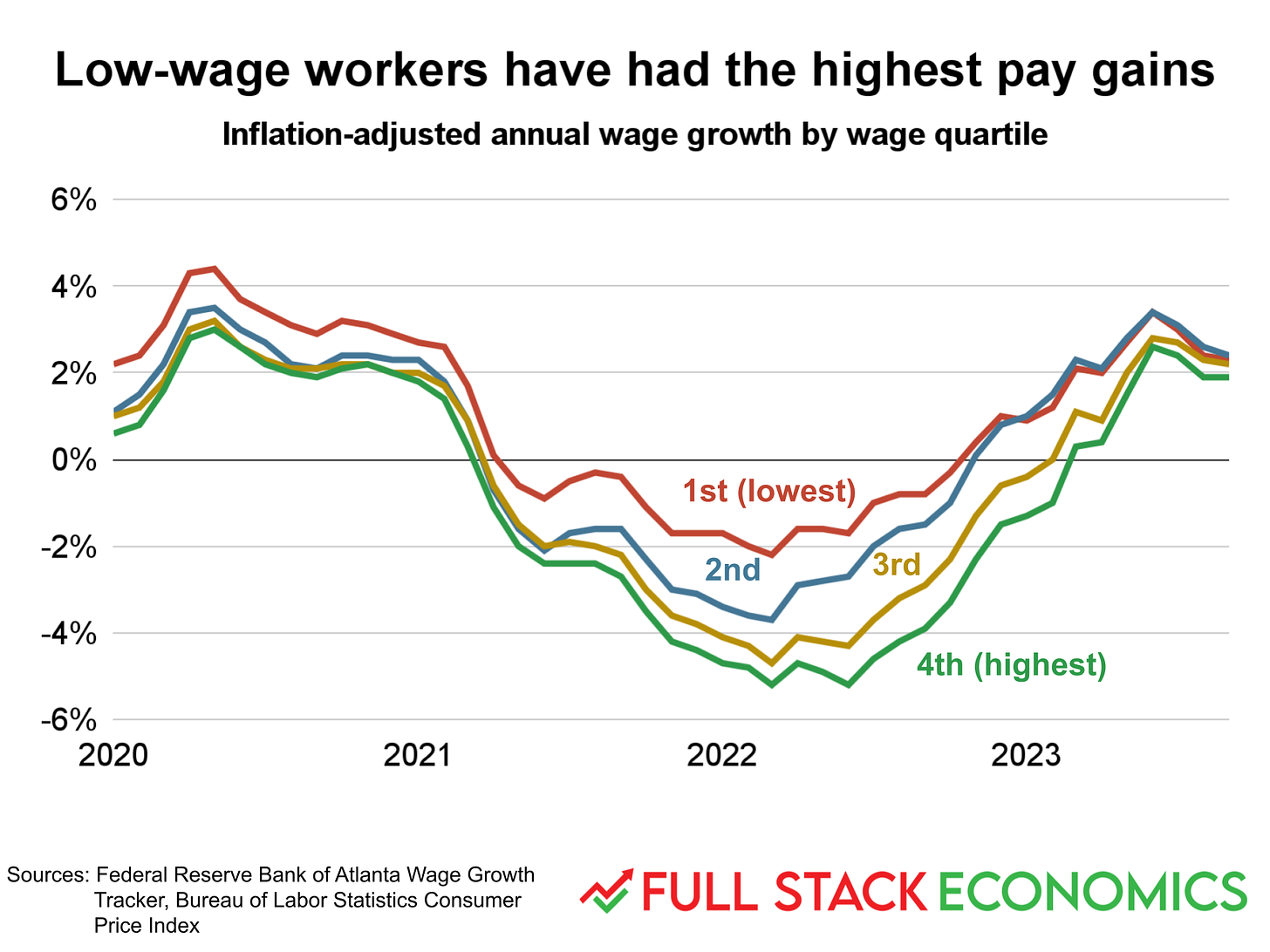

Average real wage growth was negative for most of 2021 and 2022, largely because companies can update their prices faster than workers can negotiate wage increases. But over the last year, real wage growth has been positive.

Throughout this period, lower-end workers have fared better than most. Low-wage workers suffered the least wage erosion in 2021 and early 2022, and they’ve enjoyed the strongest real wage growth over the last year.

A comprehensive study of the post-pandemic labor market by economists David Autor, Arindrajit Dube, and Annie McGrew found that low-wage workers have benefited more from the pandemic-era economy than their high-wage counterparts. In fact, low-end pay gains since 2020 have erased a quarter of the increased wage inequality that occurred since 1980.

They credit this “unexpected compression” to the tightness of the low-wage labor market. Low-end workers could afford to be picky thanks to high demand for low-wage labor across many sectors of the economy.

Wage growth has moderated in the past couple of months, but job quits and job openings—measures of labor market tightness—are“still fairly elevated,” Bunker told me. And that’s particularly true at the low end of the labor market.

In response to this tightness, employers have been offering higher wages and better benefits to entry-level workers. The military, for example, has said that high wages in the fast-food industry have made it difficult to meet its recruiting goals.

“This is the most challenging recruiting environment the Department of Defense has probably ever faced,” the National Guard Association said in a June press release.

Workers who shop around have benefited the most. Autor and his co-authors found that half of the total wage gains for low-income workers over the past few years came from job switching rather than negotiating higher wages at an existing job. Proactive workers were disproportionately rewarded for their efforts, while more stationary laborers sometimes fell behind.

As Rachel, a manager at a fast-casual steakhouse, put it to me, “the power [my workers] have is in leaving, in trying the next thing and shopping around.”

The restaurant industry bounces back

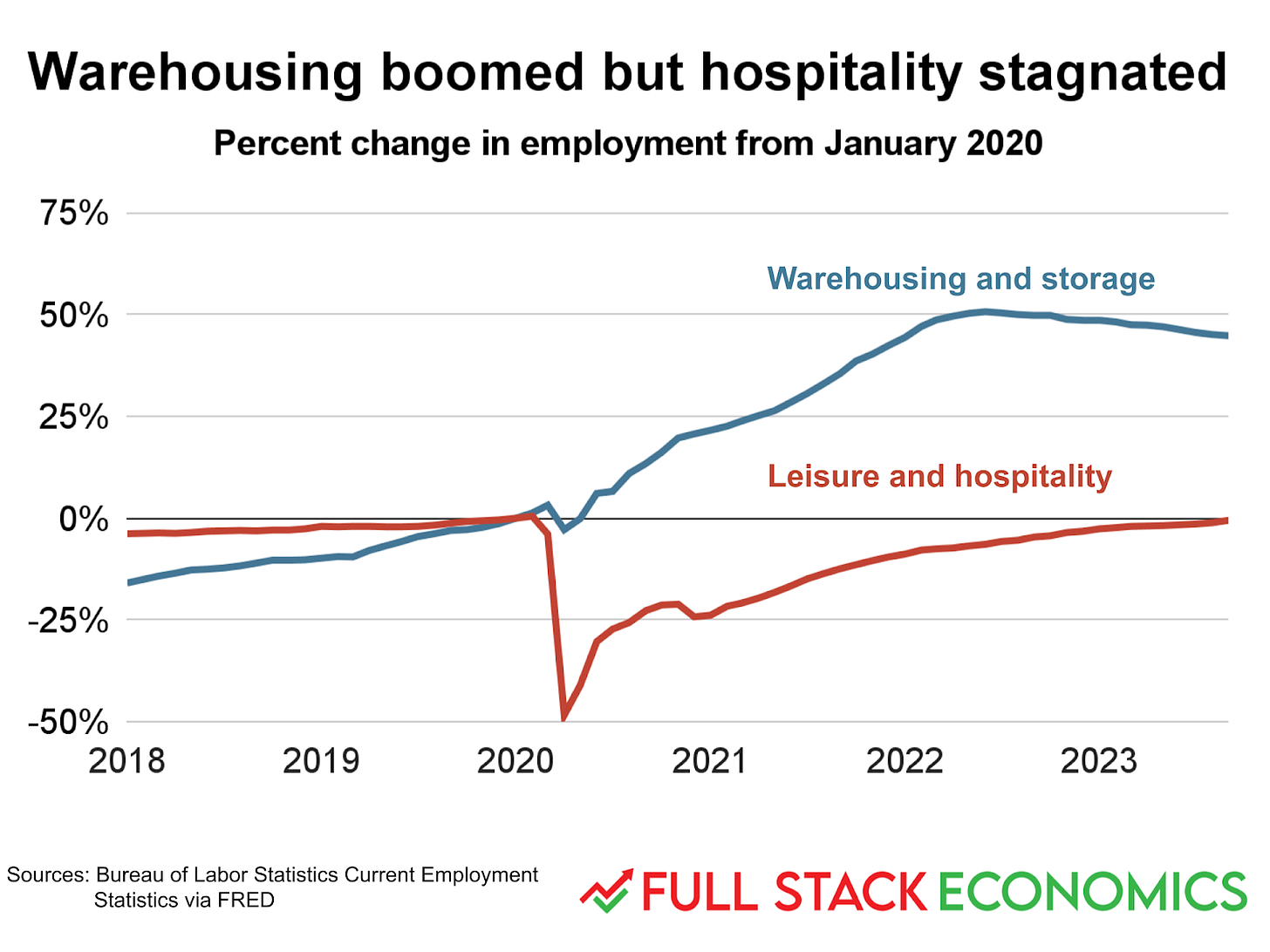

When the pandemic first hit in the spring of 2020, people stopped traveling and started shopping online. The hotel and tourism industries atrophied, while warehouse employment surged.

Warehousing jobs were “a huge growth area in the labor market particularly in the period when COVID was having the biggest impact on people’s decision-making process,” Bunker said.

At first, wages stagnated for workers in hospitality and shot up for those transporting packages. But as workers flooded out of leisure and hospitality into warehousing, hotels were forced to raise wages as well.

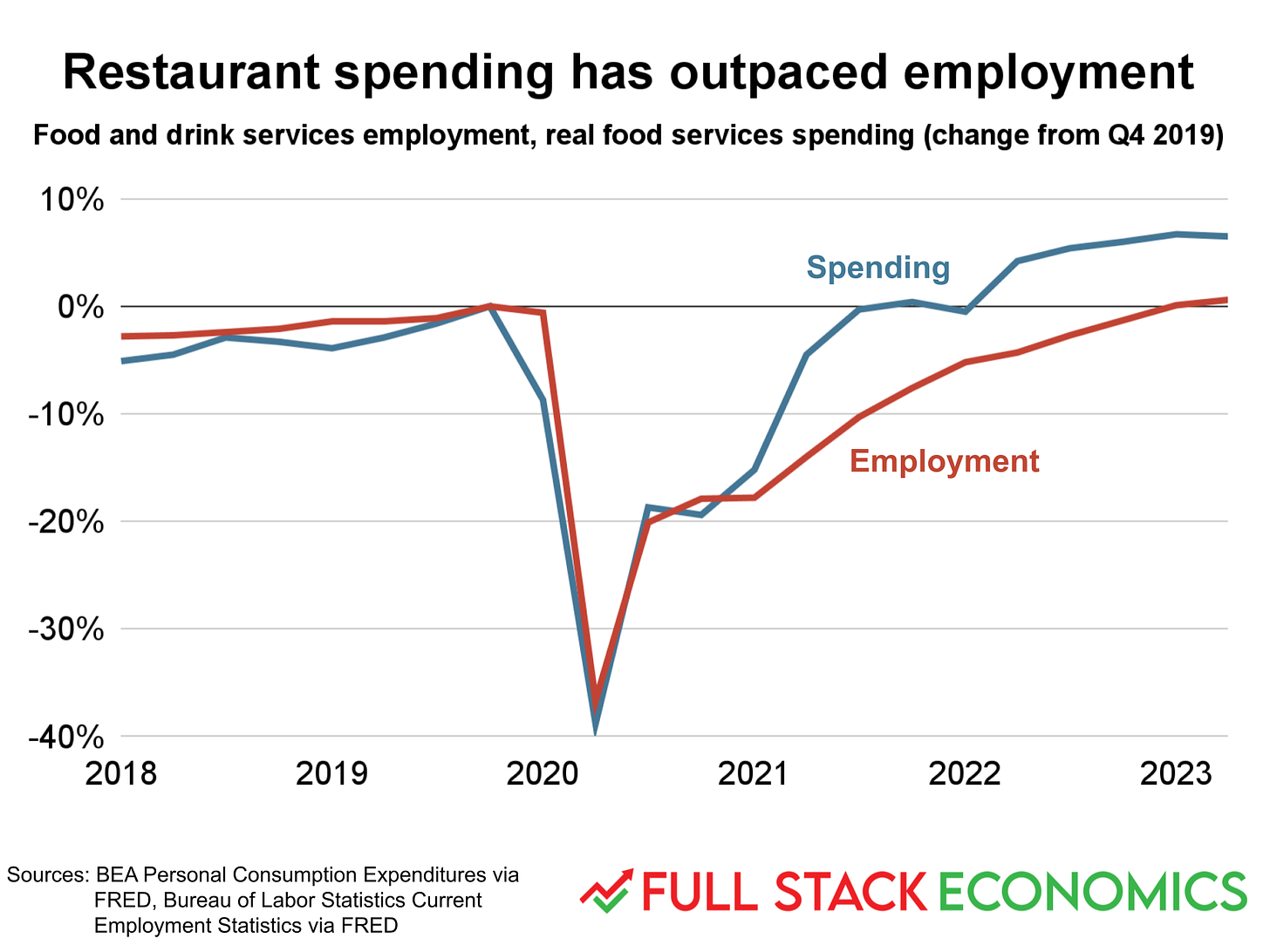

Similarly, the restaurant industry shed more than three hundred thousand workers between 2019 and 2020. It is just now recovering that gap. Meanwhile, spending on food services has not only recovered to its pre-pandemic peak but is actually 6% above it.

As a result, restaurants can afford to offer higher wages to their remaining workers. That’s good news for those workers, though they may have to work harder than they did before the pandemic.

Mike, a waiter in Los Angeles, has kept the same job the past few years. He told me he is now making more money than he did before the pandemic. His restaurant “learned that we were able to operate with less people, with a smaller workforce. So the money has been the same or better,” he said.

Rachel echoed this story, saying her steakhouse has “paid for the people that stuck around and suddenly the jobs that you had four people doing… we have one guy doing. So, yeah, give him $22 an hour to do it.”

Rachel herself is a job-switcher. She previously had a job doing political strategy work, but she started to feel burned out. She took a job in the restaurant industry and has worked her way up into a front-of-house management role at a fast-casual steakhouse.

Workers have also benefited from changing jobs within the restaurant industry. Darryl, a waiter, told me he took the opportunity to move “into more upscale dining,” and, as a result, has “been able to stay ahead of inflation.”

Not everyone has benefited

Karen, a New York security guard, has not seen her salary keep up with inflation. As a result, she's struggling to buy groceries for her family of four. She told me that she has thought about trying to get a new job, but she’s too worried a new job might be worse.

Similarly, John, who has been a delivery driver since the start of the pandemic, told me his commissions have fallen while prices have risen. That’s why he called the current life of a delivery driver “a fight for survival.”

Why have some workers who kept their jobs gained while others suffered? The answer goes back to the newfound worker power identified by Autor and his co-authors. Some workers like John happened to work in an industry—delivery driving—where workers had little bargaining power. As a result, they haven’t been able to get raises to offset the rising cost of living.

I don’t want to second-guess the decisions of individual workers such as Karen and John who may have specific reasons for holding on to their current jobs. But the evidence suggests that a lot of workers in their position—suffering from low and stagnant wages during a generally tight labor market—would benefit from switching jobs.

Are these gains sustainable?

Even workers who have reaped the benefits of a tight labor market can’t help but wonder if heightened salaries are temporary.

On the one hand, many of the gains from the temporarily hot—what economists call cyclical—labor market are transient. Even if low-wage workers are able to get a big raise by switching jobs, they’re still at risk of being laid off if the economy slows.

“For every period with 3 percent unemployment, you've got a period like after the Great Recession, where a lot of people are losing their jobs. And so for an individual who works for 35 or 40 years and experiences downturns and booms, it kind of averages out,” David Deming, a Harvard economist who studies labor markets, said in an interview.

Bunker expressed a similar fear, saying that many low-income workers have found themselves in sectors especially subject to discretionary spending—industries that could contract substantially in a recession.

In a June paper, Demming highlighted one way workers can lock in wage gains. The research shows that educated workers earn more than their non-college-educated counterparts because over time they develop specialized skills and receive promotions. To really narrow wage inequality, Demming told me in an interview, non-college workers should find a path to the sort of “professional jobs” that allow continued advancement over the course of their careers.

“Many people who don't have a college degree end up pigeonholed into dead-end jobs that don't fully utilize their talents and capabilities and don't allow them to grow. And that seems like a real shame and a real waste of potential,” he said.

The tight labor market has meant rising wages for low-wage workers, but may have a secondary effect that could be more important over the long run: allowing less educated workers to get jobs that previously required a college degree.

The Burning Glass Institute, a labor research institution, found that a lot of employers are dropping their degree requirements. This trend began in the tight labor market of the late 2010s, but the pandemic has accelerated it. Similarly, a January survey found that as many as 34% of employers had dropped degree requirements in the last year with the goal of attracting more applicants.

Moving into jobs that previously required more education isn’t the only way to move up the career ladder. Rachel took advantage of the pandemic labor market to “work [her] way up” by moving to the restaurant sector and then staying in the same job. She received training, became a manager, and now has skills that could translate into permanently higher wages. Similarly, Darrell’s move into high-end restaurants may provide him with a new and distinct skillset.

So while some workers have exploited newfound bargaining power to get raises above the rate of inflation, the long-term winners of this economy may be those who move into jobs or sectors formerly closed off to them.

Aden Barton is an economics student at Harvard. You can follow him on X.