The end of Silicon Valley’s 20-year boom

Tech layoffs could mark the start of a new era for Silicon Valley.

The last month has seen a bunch of big technology companies—including Meta, Twitter, Lyft, Salesforce, Microsoft, and Stripe—announce layoffs. Now the New York Times is reporting that Amazon is preparing to lay off around 10,000 workers in its corporate offices.

These tech-industry job cuts have come in the face of new data showing that hiring in the broader economy remained strong in October. Companies added 261,000 workers, beating analysts’ expectations. So it looks like Silicon Valley is tightening its belt more than other industries.

I suspect this reflects a significant change in the economics of the sector. For the last 20 years, Silicon Valley has had the wind at its back thanks to rapid adoption of new technologies like the internet and smartphones. As a result, the industry fared better than the broader economy during and after the 2008 recession.

But the internet is maturing and as a result big tech companies don’t have the same growth potential today that they did in 2012 or 2002. Investors, recognizing that, are increasingly demanding that tech companies focus on profits rather than growth. And that means there could be even more pain ahead for Silicon Valley workers.

It also means that the phenomenal deals tech companies like Uber and Doordash offered to consumers in the 2010s are unlikely to come back. Back then, venture capitalists were willing to subsidize rides, deliveries, and other services in a bid to expand their market share. But now these markets are becoming saturated, and investors want to see a return on their past investments. All together, it could make for a less dynamic internet to live on—and, perhaps, a less lucrative industry to work in.

The tech bubble that wasn’t a bubble

In 2007, a video called “Here Comes Another Bubble” made the rounds on tech blogs. It started with a clip of PayPal co-founder and early Facebook investor Peter Thiel declaring that “there’s absolutely no bubble in technology.” Then it showed a series of tech valuations that were seen as ridiculous at the time, including YouTube at $1.6 billion, Skype at $2.6 billion, and Facebook at $15 billion.

Today we know these valuations were entirely reasonable—even cheap. Microsoft acquired Skype for $8.5 billion just three years later. The year after that, Facebook had an initial public offering that valued Facebook at more than $100 billion. It’s safe to say that YouTube, now a Google subsidiary, is worth a lot more than $1.6 billion today.

But in 2007, fresh memories of the 1990s tech bubble made people wary of investing in technology. As a result, they consistently underestimated how valuable internet companies would become. In 2012, many people were astonished when Facebook paid $1 billion for Instagram, a two-year-old company with only 13 employees—even though the app had tens of millions of users and was growing fast.

Google and Facebook faced questions in their early years about whether they would ever make money. But these doubts were silenced once they started selling targeted ads on a large scale and raking in billions of dollars.

As these pioneers got more and more profitable, the conventional wisdom shifted. The pessimism and conservatism of the 2000s gave way to growing optimism. Over the course of the 2010s, more and more money flowed into Silicon Valley’s venture capital firms, and those firms became more and more willing to absorb losses in the short term in pursuit of rapid growth and—they hoped—long-term profits.

Software eating the world

At the same time, the supply of promising new internet startups that needed capital was dwindling. In the 1990s and early 2000s, entrepreneurs invented big new product categories like search engines, social networks, and video streaming services. By the 2010s, these had become mature industries, and it was getting harder to come up with genuinely original ideas for a new website or app.

Venture capitalist Marc Andreessen provided a possible solution in a famous 2011 essay called “Why Software Is Eating the World.” Prior to 2011, Andreessen argued, Silicon Valley had mostly disrupted information-oriented industries like music, books and movies. But in the 2010s, software was poised to revolutionize much more substantial industries like health care and education.

Uber and Airbnb quickly emerged as poster children for this kind of thinking. The 2010s saw a proliferation of “Uber for X” startups that sought to use smartphone apps to transform a wide range of traditional industries. A few years later, startups like Bird and Lime started raising millions of dollars to litter the sidewalks of American cities with scooters.

Because the “world of atoms”—industries like health care, transportation, or real estate—was much more economically significant than the “world of bits”—industries like music, video games, social networks, and the like—optimists hoped that this new generation of tech startups would be more valuable than the old ones.

In 2017, Japanese billionaire Masayoshi Son founded the Softbank Vision Fund to dump an unprecedented $100 billion into the still-expanding tech sector. But there was less and less tech in these “tech startups.” One of Softbank’s biggest investments was in WeWork, a co-working company that managed to brand itself as a tech startup—and raise money at tech-startup valuations—despite being in the old-fashioned commercial real estate industry.

What WeWork, Bird, and Uber shared with earlier generations of tech startups was a conviction that it made sense to focus on growth first and worry about profitability later. But while this strategy made good sense for Google and Facebook—who were pioneering entirely new software-based industries with low marginal costs—it made less sense for companies entering existing industries like taxis or commercial real estate. The profit margins on these more tangible products was never going to be as good as a search engine or social network—and to even get to the point of profitability, these companies plowed fortunes into consumer subsidies that couldn’t possibly be maintained long-term.

The macroeconomic context was important here. The 2010s were a period of low interest rates and high stock valuations, which meant that institutional investors—people managing investments for universities, pension plans, wealthy families, and so forth—were desperate to find ways to deliver better returns for their clients. Many of them invested in venture capital funds that in turn invested in startups. As long as the paper value of these investments was rising, nobody involved in the industry had much incentive to ask if those valuations were sustainable.

This boom started to lose momentum with the near-collapse of WeWork in 2019, got a second wind in 2021 thanks to trillions of dollars of stimulus spending, and then faced a much more serious reckoning in early 2022. That’s when the Federal Reserve started tightening financial conditions to fight inflation, which caused investors to focus less on growth and more on profitability.

And this new focus was an unwelcome shock for many of these companies. Bird’s market capitalization has declined by 95 percent since it went public late last year. Lyft is down 84 percent since it went public in 2019, while Uber is down 30 percent. WeWork is worth $2 billion, down about 95 percent from Softbank’s last investment round in 2019.

Labor market impact

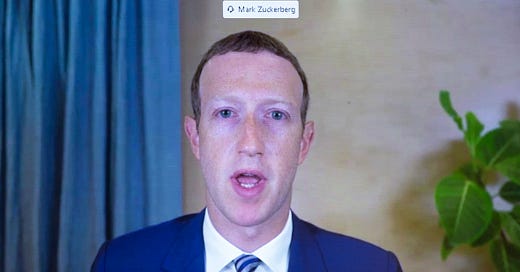

The last year has also been hard for more traditional internet companies. Meta, the parent company of Facebook, has lost 70 percent of its value since its 2021 peak, while Google is down 36 percent. These are not catastrophic declines for these companies because they come on the heels of massive gains in previous years. But it may have big implications for Silicon Valley as a whole.

When an industry is growing fast, being understaffed tends to be much more costly than being overstaffed, because it means missing out on big growth opportunities. Companies like Twitter and Lyft have maintained large staffs of well-paid engineers to try to keep up with bigger rivals Facebook and Uber, respectively. Until recently, companies like this bought into the idea that they should focus on growth now and worry about profits later.

But this strategy only makes sense in a fast-growing industry, and that no longer describes a lot of Silicon Valley companies. Once growth slows, then profits matter more and companies will naturally look for ways to cut costs. So with a potential recession looming, we’ve started to see a bunch of technology companies announce layoffs.

I suspect there is going to be room for additional belt-tightening for years to come. Part of what made the technology sector so exciting for investors in the first place was the prospect that a fairly small number of people could write software that would be used by billions of people. Once it becomes clear that the era of rapid growth is over, technology companies will focus more on realizing this potential by streamlining operations and cutting nonessential projects.

And ultimately this could be good for the economy as a whole. In recent days I’ve talked to multiple software professionals outside of Silicon Valley who told me that there is a persistent shortage of experienced engineers in the broader economy.

The marginal worker at Google, Meta, or Uber might actually produce more value for the economy if they worked at a mid-sized retailer, manufacturing company, or hospital. In the past, Silicon Valley could capture many of the best engineers by offering them stock options that became worth a lot as their stock rose. But in an era of rising interest rates and falling share prices, that won’t be such a draw.

How bad things get depends largely on what happens in the broader economy. If the Fed tips the U.S. into a severe recession, we could see a lot more layoffs in the coming months and incumbent technology companies could be forced to get leaner in a hurry. On the other hand, if we have a mild recession—or no recession at all—in 2023, that could allow for a more gradual transition. Either way, it’ll be a different industry from here on out. Software will have to eat something else.

The problem with tech market profits is that it is beginning to dawn on users that it is they who are being used. Apparently, everybody has to relearn the first law of consumerism, nothing is free. And the second law is, nothing is safe.

You said that many tech companies were "desperate to find ways to deliver better returns for their clients." That is a big lie. The only think that any company is desperate to do is to turn a profit. And everyone should understand that and to expect it. After all, that is what drives any economy.

The weakness of that is it is often more money to be made, at least in the short term, cheating clients and abusing them than in giving them better returns. If I learned anything in business school, it is that corporations make more money in manipulating their stock prices than in making and selling product.

Tech companies rake in most of their income from selling advertisements and selling their users' personal information to those advertisers and, especially since 911, to governments, both domestic and foreign. All companies have cut costs by outsourcing labor to countries who keep labor costs down by keeping they subjects in slave-like condition.

The second cost cutting strategy is to eliminate customer service. The first step in that was to outsource help desks to India, Indonesia and China. After enough people quit calling for help out of frustration with inability to communicate with the people answering the calls, they could just quit providing a call-in number completely.

I suspect that the prime use that tech companies use software engineers for is to hack users' computers and other electronic devices to enhance the information they gather from their clients and from their competitors. One of the most lucrative businesses is with the two major political parties, for they will do anything to get their candidates elected and re-elected. There are trillions of dollars to be milked from the seven plus billions of governed people in our world.