Sorry, deficit hawks: low interest rates are here to stay

Deficit hawks have been waiting for their moment for seventeen years. It hasn't arrived.

For the last two decades, deficit hawks have been expecting their moment: a time when sober-minded people are once again called upon to make hard decisions to get our fiscal house in order.

They have—or at least, at one point, had—a specific, clear idea of what that moment would look like. The hawks’ arch-villain, the national debt, would cause a series of well-known economic problems. Then you would call in the deficit hawks to fix the problem, much as you'd respond to a jailbreak at Arkham Asylum by putting up the Bat Signal.

That scenario hasn’t materialized at any point in the 21st century. The clouds over Gotham remain unilluminated. The national debt has increased substantially over the last two decades, and the economic indicators that would signal a Deficit Hawk Moment have never shown themselves.

Below I will explain why their moment never arrived, and why that moment may continue to elude them for quite some time.

Portrait of a Deficit Hawk Moment

The nature of a hypothetical Deficit Hawk Moment was clearly outlined by Democratic macroeconomists led by former Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin, about halfway through George W. Bush’s tenure. A landmark 2004 paper argued that the Bush administration’s budget deficits were going to endanger the economy.

It is important to be precise about the nature of the critique here: it was not merely the ordinary Democrat’s critique that President Bush had used fiscal capacity on things like tax cuts and wars instead of Democratic priorities. This was specifically a macroeconomic critique: that the level of deficit spending, per se, would create a crisis, regardless of what priorities created those deficits.

This viewpoint would be adopted by many others—not just Democrats, but Republicans and nonpartisans as well. And it would be adopted not just in response to Bush, but also in response to later presidents. For example, a few years later Republicans like Rob Portman and Paul Ryan were saying similar things about President Barack Obama’s policies.

The Rubin report made some clear and specific predictions: deficits would lead to a “loss of investor and creditor confidence” that would lead the world’s bond market to “demand sharply higher interest rates on U.S. government debt.” That would lead to high interest rates generally, which would hinder private investment. They thought the next president would need to bring deficits back down in order to stop all this from happening.

This thesis had a lot going for it. First, it made falsifiable predictions—for example, of rising bond yields—that are easy to check after the fact. It followed coherent economic logic; it would make sense that increased borrowing would allow lenders to extract more favorable terms, especially if they lacked confidence in the borrower. Finally, it had some basis in history. Rubin had led President Bill Clinton’s team, which inherited a budget deficit and high interest rates, and they had achieved success by raising taxes and restraining spending as a percentage of GDP. The bond market calmed, reducing the cost of capital economy-wide, and it fueled an investment boom. The higher deficits of the 2000s, it was thought, would reverse those gains.

Most importantly, the thesis was politically ascendant. In the first chapter of his 2018 book Crashed: How a Decade of Financial Crises Changed the World, economic historian Adam Tooze lays out just how defining this thesis was to mid-2000s Democrats. He opens with a portrait of the 2006 launch of the Hamilton Project, a Brookings Institution fiscal policy center with a mission heavily inspired by that 2004 paper. Barack Obama, then a Senator, gave the keynote address, with some of his most important future economic advisors in attendance, and advocated keeping deficits low. Rubin touted his work showing “deficits are highly relevant with respect to interest rates.”

But there was one big problem: the predicted higher interest rates never came to pass.

Interest rates fell instead

Bush did indeed lead the nation into crisis in 2008, but it was the opposite of what the Rubin thesis predicted. Interest rates went down, not up. People liked the dollar and Treasury bonds too much, not too little. As private-sector investments looked increasingly shaky, the guaranteed return of government bonds, even at low rates, looked increasingly attractive.

There were deep problems with economic policy under the Bush administration, but not the problems Rubin predicted. In fact, the first chapter of Crashed is titled “The Wrong Crisis,” after a 2008 blog post by Brad DeLong, another Clinton Treasury alumnus. DeLong quickly realized the situation was vastly different than anticipated, and adapted. He called for “coordinated fiscal expansions across the globe.” Other Democrats followed, and by the time Obama actually took office, he was looking to increase deficits through a fiscal stimulus bill, not decrease them.

The Rubin thesis missed its moment, or perhaps, that moment never existed in the first place. The next two decades buried it.

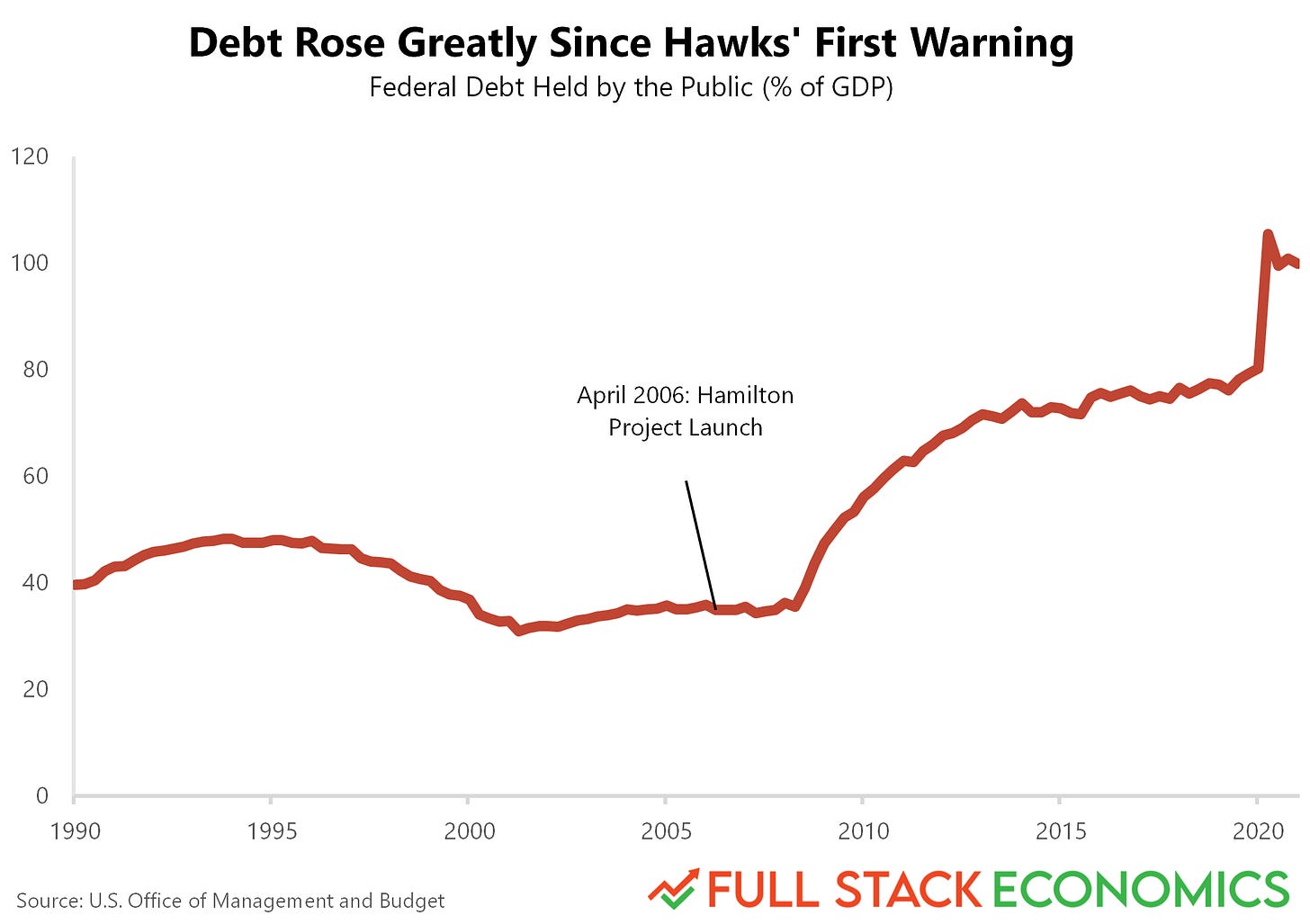

In 2006, the year of the Hamilton Project keynote, the federal debt held by the public stood at 35 percent of GDP. Since then, governments of both parties have ignored the prescriptions from that launch event and borrowed even more money, bringing the debt to 100 percent of GDP.

A long series of events created that outcome. Two recessions reduced market incomes and tax revenues. The Bush wars continued. Some Bush tax cuts were made permanent. Obama enacted a fiscal stimulus. He also spent on health care through the Affordable Care Act, even as many of the tax provisions intended to pay for it were delayed and eventually repealed by Congress. President Trump signed additional tax cuts and COVID relief bills. President Biden added COVID relief of his own.

At the time the Hamilton Project convened, the U.S. ten-year borrowing rate was about 4.8 percent. However, rather than playing the role of the “vigilante,” the bond market seemingly fell asleep at the switch. It did not discipline the federal government by selling off bonds; it bought even more of them, and offered even more attractive terms. The ten-year borrowing rate fell dramatically over the next seventeen years, and stands at just 1.3 percent today.

So what happened? Why did rising deficits not result in rising interest rates, as Rubin, or other deficit hawks after him, predicted? The world has shifted under our feet over the last 30 years.

Aging populations save more

Around the same time that the Clinton treasury alumni were advancing the debt crisis thesis, Ben Bernanke, then a member of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, was beginning to outline a different one: that there was a growing surplus of savings worldwide. While much of Bernanke’s seminal speech on the subject focused on trade deficits, it also discusses global saving as a contributor to falling interest rates.

Not all of Bernanke’s speech remains valid today. A lot has changed in the last 16 years. But the speech is important because it recognized low interest rates as a burgeoning global trend, and described some long-run factors that still influence interest rates today.

The most important of these is the impact of an aging population on capital markets. As Bernanke put it, “one well-understood source of the saving glut is the strong saving motive of rich countries with aging populations, which must make provision for an impending sharp increase in the number of retirees relative to the number of workers.”

Here is where that motive comes from: for most individuals, wage and salary income peaks in middle age, and then drops dramatically in retirement; they save to preserve some peak income for retirement.

As Bernanke said in 2005, this observation was not particularly new. In fact, most of his curiosity concerned the increase in saving in middle-income countries. This surprised him, because at least at the time, he did not consider developing countries (with the exception of China and its one child policy) to have aging populations.

But a reader today should note that the demographic explanation was pretty strong, even at the time. A list of aging countries that includes developed countries plus China means nine of the world’s ten biggest economies by GDP.

The explanation has only grown stronger. Since Bernanke’s speech, the entire world has aged substantially. Even India, the only one of the world’s 10 largest economies that is not traditionally considered to have an “aging population,” will by 2028 resemble the age distribution of South Korea circa 2000.

There are about 700 million senior citizens in the world, and this number grows by about 30 million each year. These people need to save. As they approach retirement age they lose the relative certainty and predictability of future paychecks. They naturally benefit from a more conservative investment portfolio. That means holding more bonds.

This is even true when they invest through an intermediary, such as pension funds. Pension funds love bonds, because bonds allow them to do something called “asset-liability matching.” Funds tally up the benefits they have promised to the expected number of living retirees or beneficiaries each year. The safest way to cover these is with bonds that provide cash inflows, through predictable coupon payments or principal repayments. When funds get a stream of cash inflows that perfectly matches the projected outflows, they are happy.

Pension funds are huge. Some of the largest include Texas and California public employees funds, which have hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of assets each. Overall, the worldwide pension industry has as much as $50 trillion in assets. These funds will continually bankroll new lending and reinvest in debt. So long as they have future retirements to fund, they will never “call in” their lending. Defined-benefit plans are just going to keep asset-liability matching, even if interest rates are unfavorable to them.

Young people can borrow and absorb some of this lending, but there aren’t enough of them to absorb all of it. The aging trend creates a persistent supply of savings that only grows with each passing year, and it exerts a powerful downward force on global interest rates.

Business investments aren’t as capital-hungry as they used to be

One outlet for saving is business investment. While individuals, institutions, and even countries can save by lending to each other, this creates no net saving worldwide: any lending by one person or institution is perfectly canceled out by dissaving by another. The only way for the world as a whole to save is through valuable real investments. For example, if you are a farmer and you own a combine harvester free and clear, then you have an asset, but there is no liability to cancel it out. In that case the world as a whole has saved. Ideally, we’d be able to use the world’s increased savings to produce more buildings, factories, machines, and other durable capital assets.

This outlet for savings has sometimes been robust. Consider the Transcontinental Railroad, a 2,000-mile rail line that connected Council Bluffs, IA to Oakland, CA in 1869.

The Transcontinental Railroad alone—just one of many railroads criss-crossing the country—needed tens of thousands of workers. The Central Pacific Company, responsible for the main western leg of the line, famously put out an advertisement for 5,000 workers in the Sacramento Union at a time when the entire population of Sacramento was no more than about 15,000 people. This was a massive undertaking for a country that had barely one tenth of today’s US population.

While the total cost of the railroad is not precisely known to historians, estimates put it in the range of $100 million, much of it raised in bonds. Total GDP for the U.S. was about $7 billion. As a fraction of GDP, this would be the equivalent of a multi-hundred-billion-dollar project today.

Somebody had to buy the railroad bonds that financed all that spending. In 1869, there were few affluent late-career workers desperate to save money for their golden years. So somebody had to defer consumption so that resources could be diverted to railroad construction. To convince people to volunteer, railroads had to sweeten the pot with interest rates as high as 6 percent.

In contrast, a lot of 21st century investments don’t require much capital to get off the ground. Consider Instagram’s short life as an independent company. It raised just $57.5 million from venture capitalists before being acquired for $1 billion by Facebook in 2012. At the time of its acquisition, it famously had just 13 employees. Today, as a component of Facebook, it is worth hundreds of billions of dollars.

Building Instagram required risk-taking, talent, vision, and luck. But it never needed to borrow large sums of money, relative to the massive quantity of willing lenders. Furthermore, the global nature of the Internet means that the world only needs a handful of large social media networks, which limits the total amount of capital this industry requires.

I have described this phenomenon anecdotally thus far, but you can also see it when you look at the data. To do this, you need to look at business investment as economists would define it, which is business expenditure on long-lasting inputs to their production process. (This lies in contrast with investment as a financial advisor might define it.) Despite steadily declining interest rates since 1980, net nonresidential investment has fallen, not risen.

Economists often say that saving and investment are necessarily equal, for certain definitions of “saving” and “investment” in a closed system. But it’s important to consider this relationship very precisely. It does not mean that more saving will causally result in more investment activity. Instead it just means that the net value of our financial assets equals the value of our real-world assets, at current market prices.

In theory (and, we have frequently found, in practice) our collective net worth can appear to rise simply because we bid up the value of pre-existing assets rather than creating new ones.

One thing that the surplus of savers have bid up is the price of bonds; this means accepting lower coupon payments or future returns, relative to what you paid for them. In other words, it means lower yields.

Countries can borrow more sustainably than before

Countries, especially those that issue their own currency, can take advantage of low yields and borrow much more money at much lower rates than ever before.

Here is what debt service for the U.S. looks like: interest payments as a percentage of GDP were as low in 2020 as they were when the Hamilton Project keynote address was delivered (about 1.6 percent of GDP) and even lower than they were during the Clinton administration.

Many of the world’s largest and wealthiest economies charted the same course from the mid-2000s. For example, the United Kingdom’s debt has risen similarly to that of the United States, and it pays less than one percent to borrow.

The best example of all these trends in action is Japan, which is famous for having a relatively old population, a debt well past 200 percent of GDP, and low interest rates. While it might seem like Japan should be a target for “bond market vigilantes”—traders who sell off a country’s bonds and force them to borrow at higher interest rates—none of that has happened, even though this situation has persisted for decades.

Japan’s elderly population accepts the low yields because they need to defer their spending power. Japan, therefore, has a surprisingly large fiscal capacity relative to its GDP. While Japan was the earliest example, the rest of the world is coming to resemble Japan, and savers have little recourse.

There are some caveats. The mechanics for “borrowing” are a little bit different for countries that print their own currency; they don’t technically “need” to borrow, since they issue their own currencies. They also at least appear to be able to set their own interest rates through their central banks.

However, neither of these distinctions is as large as it seems. Countries issuing fiat currencies do not want too much money being spent too quickly and chasing too few goods, driving up spending past the economy’s ability to produce. That could reduce confidence in the value of the currency and generate inflation. Colloquially, governments do not want “overheating.”

It turns out that older people with higher propensities to save help cool down the economy. Because they are willing, or even eager, to defer spending, they tend to spend little, even when their balance sheets are strong. Currency-issuing governments are not like private borrowers, but they do still rely on savers’ willingness to defer spending until later. As the supply of would-be savers becomes more ample, so too does government fiscal capacity.

Some people mistakenly believe that today’s low long-run interest rates are a deliberate policy choice of central banks. It’s true that central banks can control the rates on short-term debt in the near term. But central banks face significant constraints over longer time periods. If they try to push rates in the “wrong” direction, this will lead to harmful consequences like high unemployment or high inflation. So the decades-long trend of falling interest rates is fundamentally driven by market forces, not the whims of central bankers.

These forces are hardy and durable

The forces I describe here—simple shifts in supply and demand—are powerful, and they’re unlikely to change any time soon.

Theoretically, you can imagine Elon Musk announcing a plan for a $50 trillion space station that would produce trillions of dollars in value once it was fully operational. As Musk (or supporting governments) scrambled to raise the necessary capital, lenders would enjoy increased bargaining power, and interest rates would rise accordingly.

But a scenario like this doesn’t seem very likely. Even today’s most ambitious capital projects—say, high-speed rail projects or massive new factories—tend to have costs in the billions, or occasionally tens of billions, of dollars. And these kinds of projects are becoming less common as population growth slows and we spend more time online.

Another scenario: perhaps we’ll invent an anti-aging treatment that allows people to work productively and happily long after 65. With decades of work ahead of them, workers in their 50s and 60s might cut back on their retirement savings. Older workers might start spending down their retirement savings more rapidly to enjoy a higher standard of living. In that world, we might expect interest rates to rise.

But again, this doesn’t seem very likely—at least not in the next few decades.

It’s more likely that we will see the ranks of savers continue to grow. The median age in many developed countries will approach 50. Late-career workers will look to save even more than prior generations, and look to government bonds as an option.

Low rates are probably here to stay

In the 1996 blockbuster film Independence Day, the president reluctantly deploys nuclear weapons against a giant, hostile alien warship hovering over Texas. When the dust settles, he finds to his horror that the ship remains in the sky, unscathed.

The world finds itself in a similar situation with respect to falling interest rates. During the COVID-19 era, governments have arguably undertaken the most dovish borrowing spree in history. It hasn’t reversed the decline in interest rates. Biden’s signature COVID relief bill released more money into a supply-constrained economy and raised inflation—which could raise nominal interest rates if it remained persistent—but close readers of the data make a good case that this is abating, and investors are betting it won’t stay for the long term. We will address this more in future posts.

All of this suggests that the forces driving interest rates down will be with us a long time and are more powerful than most people anticipated.

A variety of crises, from September 11th to the 2008 housing bust to the COVID-19 pandemic, have provided us with excuses to explain away long-run trends as temporary. Once things are back to normal, we say to ourselves, we will return to the economic environment of 1994 where interest rates are high again.

But that explanation wears increasingly thin over the decades. This is our new normal.

Feature image shows former Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin speaking in Philadelphia in 2008. Courtesy of The World Affairs Council of Philadelphia.