Thanks for all the great questions! I’ll answer three this week and save the others for future posts.

The slow progress of self-driving cars

Brian T asks: “How has your view of the prospects for self-driving cars changed in the past five years?”

Five years ago a lot of people—including me—thought self-driving cars would be widely deployed by now. We were obviously too optimistic. But in the last couple of years the pendulum has swung too far in the other direction. A lot of people now think real driverless vehicles are decades away or may never be possible. I think this view is wrong too.

There’s a useful analogy to speech-recognition software. It first came on the commercial market in the 1990s, and it didn’t work all that well. During the late 1990s and early 2000s, a casual observer might have thought that not much progress was happening with the technology. But researchers kept plugging away at the problem, and in the early 2010s we saw the emergence of Alexa, Siri, and other voice-recognition platforms that worked quite well.

I think self-driving cars today are about where speech recognition was in the 2000s. Right now, Waymo is running an honest-to-goodness driverless taxi service in the Phoenix suburbs. But Waymo’s software can’t yet drive confidently in more challenging environments, like urban downtowns or the dropoff areas of airports. And a taxi service probably needs to serve those areas to be profitable—which might be why Waymo hasn’t expanded more quickly.

But the quality of Waymo rides is steadily improving. Waymo vehicles today drive more confidently and are less likely to get confused by unusual situations. I think it’s only a matter of time before they are good enough to operate in downtowns, airports, and other challenging environments. And at that point, the economics of the technology will get much more favorable, and I expect companies like Waymo to expand rapidly.

Undershooting inflation in the 2010s

Frank G has a question about inflation:

For most of my adult life, inflation has been under target. Without the knowledge needed to evaluate this, it seems like this last surge of inflation is making up for past low price rises. If we look back to 2008 or so, how does the cumulative inflation we did see compare with what we would have seen if we had consistently hit the fed target rate? What are the major effects of having all your inflation happen at once, rather than the death by 1000 cuts that could have happened under a sustained predictable growth rate?

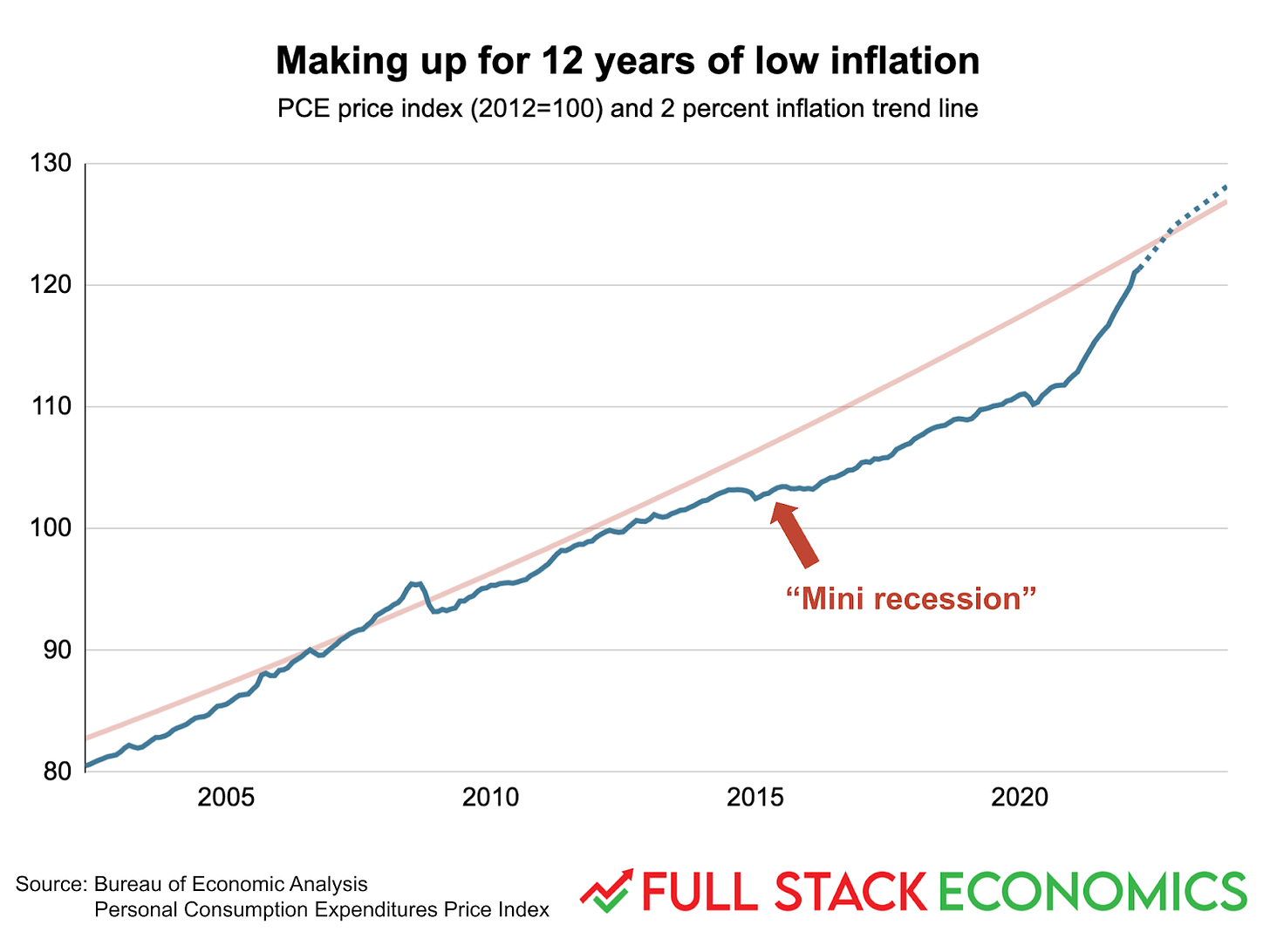

I love this question because I can make a chart to help me answer it!

The Fed’s 2 percent inflation target is based on the personal consumption expenditures price index, not the better-known consumer price index. The PCE index tends to run a bit lower than the CPI, so a 2 percent target for the PCE index corresponds to a CPI target a bit above 2 percent.

Anyway, I made a chart showing PCE inflation over the last 20 years (blue) along with a 2 percent trend line starting in July 2007. As you can see, inflation fell far below this trend line during the 2010s. But at this point it has almost caught back up. The dotted blue line on the right extends the data through the end of 2023, assuming that the inflation forecast the Fed released on Wednesday—5.2 percent inflation in 2022 and 2.6 percent in 2023—comes true.

As you can see, we haven’t quite returned to the trend line, but we’re very close and are likely to pass it later this year. When the Fed announced its Flexible Average Inflation Targeting regime in 2020, no one expected this to mean the Fed would try to make up lost ground from the previous decade of below-target inflation. But the Fed has now nearly done that, and if it doesn’t get inflation down soon, the price level will rise far above this 2007-based trend line next year.

What are the effects of this kind of uneven monetary policy performance? I don’t need to belabor the downsides of today’s 8.6 percent inflation. Right now, prices are rising faster than many workers’ wages, making it harder for them to make ends meet.

I think the downsides of too-low inflation are often explained in an unhelpful way. There’s nothing inherently wrong with low inflation—people like it when their cost of living doesn’t rise very much. The reason economists view too-low inflation as a problem is that it’s often a symptom of weak demand, which can lead to unnecessarily slow growth.

The most vivid example here is in the second half of 2015. Prices actually fell slightly between August and December. Yet in December the Fed hiked interest rates for the first time in almost 10 years. The result was what the New York Times’s Neil Irwin dubbed a “mini recession”—an economic slowdown that didn’t quite meet the textbook definition of a recession. Experts told Irwin that if the Fed had followed through on plans to hike rates several times in 2016, we would have had an actual recession that year.

The low inflation in 2015 and 2016 wasn’t bad in itself, but it was a sign that monetary policy was too hawkish. Employment growth slowed to a crawl in 2015 and 2016. More dovish policies—like not “tapering” bond-buying in 2014 and not raising rates in December 2015—likely would have spurred faster job growth. And if more people had been working in 2016, Hillary Clinton might have been elected the 45th president of the United States.

The changing economics of solar panels

Andrew asks: “How have the economics of home solar panels changed in the last decade? Since a lot of government policy is state/local and quite variable from place to place, do we have enough information yet to determine which policies are helpful, hurtful, or wasteful? This can include things like the various kinds of net metering, direct subsidies for initial purchase, aid with loans.”

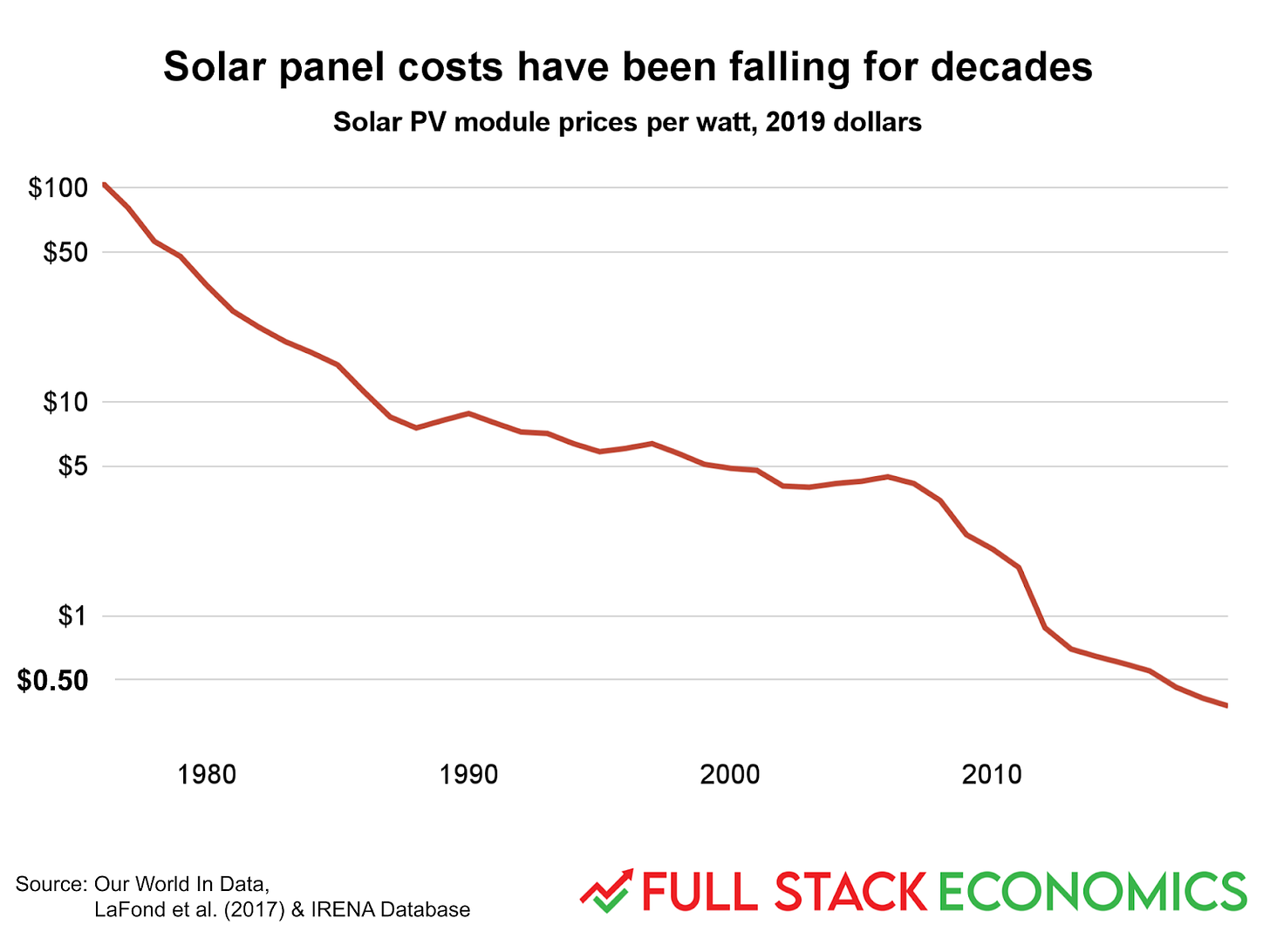

The economics of solar panels has gotten much better over the last 45 years. Back in 2019, I purchased an 8.5 kW solar system for my roof for $35,000. The same system in 1976 would have cost close to a million dollars just for the panels.

Indeed, as panels have gotten cheaper, they've become a smaller and smaller share of the overall cost of solar installations. “Soft costs” like sales and marketing, permitting, and installation labor now account for the majority of the cost of a residential solar project.

Given that, it’s not obvious to me that it makes economic sense for every homeowner to mount solar panels on their roofs. Studies have found that utility-scale solar farms are two to three times cheaper, per watt, than residential solar installations.

In the early years of the solar industry, it was important to boost solar panel output because economies of scale would bring down prices. Back then pretty much any subsidy for solar power was helpful, even if the cost per ton of avoided carbon was quite high.

But as the solar industry grows, we’re going to have to think more about how to make it economically viable as a standalone industry.

One major challenge is that solar power is intermittent—you get a lot of power in the middle of the day and none at night. This isn’t a problem when solar accounts for a small fraction of the power supply, but it’s going to be increasingly important as communities build more solar (and wind) power.

Right now, utilities often compensate for intermittent solar using natural gas turbines, which are easy to turn on and off at short notice. This works, but it’s expensive to have spare capacity that’s idle a lot of the time. And if the goal is to eventually achieve a carbon-free electricity grid, we’re going to have to find other approaches—perhaps utility-scale battery installations that store up solar power in the daytime and release it at night.

Some places have “net metering” policies where the power company has to buy solar power back from homeowners at retail rates. If a homeowner has enough solar panels to meet 100 percent of their energy needs, they wind up paying little or nothing to their power company. Yet the power company still has to maintain the power grid and the backup power sources the homeowner relies on when the sun isn’t shining.

In other words, solar customers with net metering often don’t pay the full cost of the service they’re using. That made sense in the early days as a way to subsidize the purchase of solar panels. But if everyone got solar panels, a net metering rule would bankrupt the power company.

So I think governments are going to want to change their policies as the solar share increases. For example, governments might want to follow California’s lead and require electric utilities to start building large-scale batteries. Battery technology is not yet cheap enough for this to be a cost-effective option, but battery costs have been coming down rapidly thanks in part to clean energy subsidies and mandates. If every electric utility in America starts buying batteries, costs per MWh are likely to come down faster. And utilities are going to need a lot of batteries—or some other energy storage technology—if we ultimately want to make solar or wind power a significant part of our energy mix.

More generally, I think the right approach is to set ambitious emissions goals for utilities over the next 10 or 20 years and give the utilities flexibility in how to meet them. Rooftop solar panels for homeowners might very well be part of the mix, but it may turn out that large-scale solar or wind farms are more economical.

This is a subscriber-only post. Thank you for supporting our newsletter.