Short Stack: four new econ studies you should know about

Housing shortages drive geographic sorting, but the GDPR might not have driven app declines.

Thanks for being a paying subscriber to Full Stack Economics! Our newsletter wouldn’t exist without your support. Here’s the first subscriber-only edition of Short Stack, a roundup of interesting economics news and research. As always, feedback is appreciated.

How high housing costs drive inequality and polarization

It used to be a classic American story: young people without a lot of education or connections would move to big cities in search of opportunity. Because cities were hubs of wealth and economic activity, even low-skilled workers could usually raise their wages by moving there.

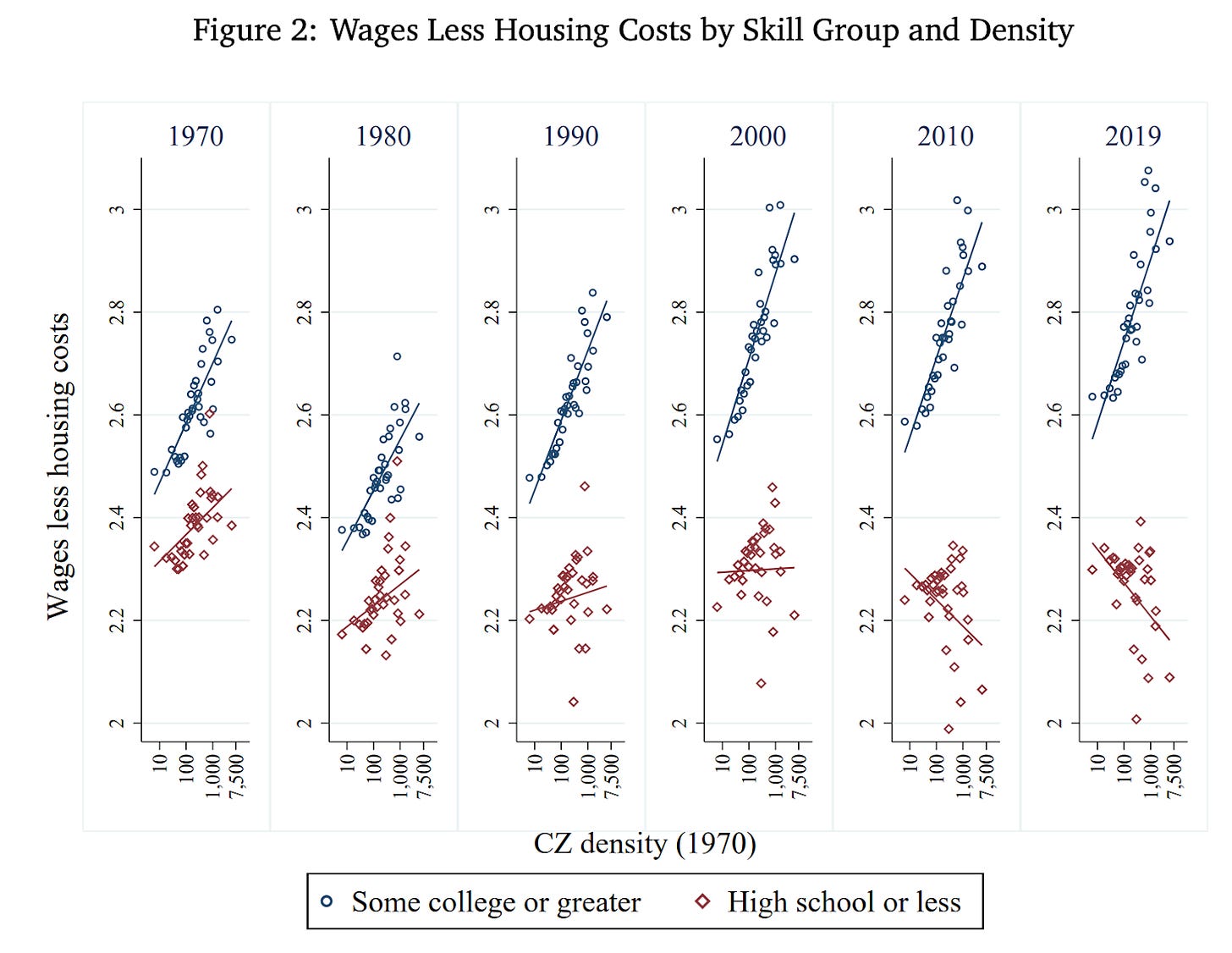

But via Alex Tabarrok, a recent working paper from the American Enterprise Institute shows that this dynamic has broken down over the last 20 years—and high housing costs are largely to blame. The change is summed up in the chart above. The X axis shows “commuting zone density”—that is the population density of various metro areas. The Y axis shows average incomes after subtracting housing costs.

In 1970, both those with college educations and those without made more money if they lived in dense urban areas—even after adjusting for the higher cost of housing there. In 2019, that was still true for college graduates, but the trend had reversed for those who didn't go to college. Now the high cost of housing more than offsets the modest wage premium for less educated workers.

I think this explains a lot about our increasingly polarized political culture. For at least the last 20 years, financial incentives have been pushing educated white-collar workers and less educated blue-collar workers in opposite directions, geographically speaking. As a result, people with similar levels of education and income are increasingly likely to live close to one another, and far away from people with different levels of income and education.

This leads to increasing political homogeneity, with urban areas becoming dominated by college-educated liberals and rural areas becoming dominated by conservatives with lower levels of education. It’s not surprising that the diverging economic prospects of these two camps has fed mutual resentment.

New Android apps plunged after the EU’s privacy law took effect

In May 2018, a new regulation called the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) took effect across the European Union. It placed strict new requirements on companies that handle user data. Last month, an international team of economists released a new NBER paper showing that the number of apps on the Google Play store plunged around this time.

“When it took effect, GDPR precipitated the exit of over a third of available apps,” the authors write. “The rate of new entry fell by 47.2 percent, in effect creating a lost generation of apps.”

The authors believe that there’s a causal relationship here, and that this represents a substantial reduction in consumer welfare. I think the EU’s privacy regime is too meddlesome, so I’d like to believe that their findings are correct. But I ultimately didn’t find their case all that convincing.

The biggest problem is that the effect doesn’t seem to be limited to the EU. The economists found that 42 percent of EU-developed apps were taken down in the year after the GDPR went into effect. They compared that to apps developed in Israel, India, Japan, Korea, Russia, and Taiwan, and found that the corresponding figure ranged from 38 to 50 percent.

Obviously, many developers create apps that are intended to be used globally, so it’s not surprising that the GDPR would have some extra-territorial effects. But if the 2018 app decline was driven by the GDPR, you’d certainly expect the effect to be bigger in Europe than in other parts of the world.

Another possible explanation for the decline is that Google itself started to crack down on privacy-violating apps around the time the GDPR was launched. Indeed, Google had blog posts bragging about the number of “bad apps” it blocked in 2017, 2018, and 2019.

Reinhold Kesler, one of the study’s authors, argues that Google can’t be the primary cause of the app decline because Google’s actions mostly happened either long before or long after the GDPR took effect in May 2018. I’m not so sure.

I don’t doubt that some app exits were driven by the GDPR. The question is how many of them were. And I don’t think this study settles the question one way or the other.

It’s also not obvious that a declining number of apps necessarily translates to declining consumer welfare. The authors argue that app popularity is unpredictable, so it’s helpful to have a lot of new apps entering the market at any given time so that we can find the best apps by trial and error. But some apps are worse than useless—they might be actively harmful to users. Moreover, sorting through a bunch of bad apps to find a few good ones isn’t free—it costs users a lot of valuable time. So if someone—either EU regulators or Google itself—forced some of the lowest-quality apps out of the Play Store, that wouldn’t necessarily be a net negative for consumers.

Households were doing well financially at the end of 2021

Each year since 2013, the Federal Reserve has conducted a survey asking consumers about the state of their personal finances. The Fed recently released a new edition of this survey covering the financial conditions of households at the end of 2021. The Fed found that 78 percent of households said they were “at least doing ok financially,” the highest percentage since the Fed started doing the survey nine years ago.

The most famous question in this survey asks consumers how they’d pay for an unexpected $400 expense. When the Fed first asked this question in 2013, only half of consumers said they’d have enough cash available to cover a $400 expense. Over the years, news organizations frequently led their coverage of the survey with this question, framing it as a sign that many American households are facing economic hardship.

At the end of 2021, 68 percent of households said they could pay an unexpected $400 expense with cash (or a credit card they paid off right away). This was the highest figure since the Fed started asking the question. The other 32 percent said they would use a credit card (and pay it off over time), borrow from friends or family, sell something, or be unable to cover the expense at all.

Obviously, the households with the lowest incomes will have the most difficulty covering unexpected expenses. But it’s worth remembering that there are also a fair number of middle-class and even affluent households that struggle to live within their means.

This week saw the release of this survey by Lending Club and PYMNTS.com. It found that more than a third of consumers making more than $250,000 “live paycheck to paycheck,” including 12 percent who do so “with difficulty.” Interestingly, a higher share of people making over $250,000 report living “with difficulty” than those in the $100,000 to $150,000 income bracket.

Obviously, no one should feel too sorry for someone struggling to make ends meet despite pulling in a quarter of a million dollars per year. But I think it’s a useful reminder that even people with quite high incomes sometimes fail to keep their expenses under control. And some of them might tell a survey that they’d struggle to pay an unexpected $400 expense.

Rent control in St. Paul triggered a 12 percent decline in property values

Last November, voters in St. Paul, Minnesota, approved an ordinance capping rent increases at 3 percent. The law, which took effect last month, is one of the most stringent in the United States. The 3 percent limit isn’t adjusted for inflation, and there’s no exception for new construction. Landlords can’t raise the rent to market levels even after a tenant moves out voluntarily.

The law does allow for landlords to petition the city for a rent increase larger than 3 percent if they can demonstrate they’ll be unable to make a reasonable rate of return at the controlled rate. A lot may depend on how much leeway city officials give landlords under this provision.

A new paper from two University of Southern California economists estimates that the law’s passage caused the value of rental property in St. Paul to fall by 12 percent. And they argue that the distributional consequences of the law have not been so progressive. They find that property values have fallen the most for homes with affluent tenants and less affluent landlords—a sign, they argue, of large wealth transfers from the landlords of these properties to their tenants.

Here’s how they explain the difference:

If properties in neighborhoods with lower-income renters also have lower expected growth in future rents, then rent control would impose a smaller constraint, and hence a smaller transfer loss... An alternative, untested explanation is that owners with low-income renters are more likely to be able to evade the law than owners with high-income renters.

The biggest downside to St. Paul’s rent control law is likely to be the way it deters people from putting new housing units on the market. But it’ll take a few years before that consequence becomes obvious.