Mailbag volume II: Buy or rent, Victoria 3, and capital taxation

Of course Alan likes Paradox games. You didn't really even have to ask.

From time to time, we’d like to answer reader questions rather than selecting our own article topics. When we solicited your questions last month, we got so many good questions that we chose to address them in multiple posts. Tim answered a set of them back in February, and I’m answering some more today. I had a lot of fun answering these, and we plan to make this a regular feature. I hope you enjoy it!

Personal finance and housing

Christian Scholz asks: If your plan as a young person is to maximize your wealth until retirement, what is the better investment strategy: buying a house and therefore saving rent or paying rent but investing your equity in stocks.

Assuming you know what kind of living space you want for the near future, a house is generally the better call. Two reasons: the first is that the house is likely to have superior tax treatment. The second is that there are inherent and (literally) costly frictions in any business relationship, including and perhaps especially landlord-tenant relationships. You avoid some of these costs by becoming your own landlord.

Owner-occupied housing’s tax treatment is better primarily because a particular style of income flies under the radar of most tax systems, known as imputed rent. This isn’t cash income, but rather, the in-kind value that you get from being able to live in your home. Alternatively, you can think of it as a rent payment you make to yourself, or the value of not having to pay rent to someone else.

You might object, and say this doesn’t count as “income.” You might object even more if I tell you that a lot of economists wish we did tax imputed rent. But the ongoing stream of benefits is real, regardless of whether you think it would be good to tax it or not.

And rest easy: the economists are never going to get their way. The absence of a transaction and the substantial voting power of homeowners makes it unlikely that imputed rent will ever be taxed.

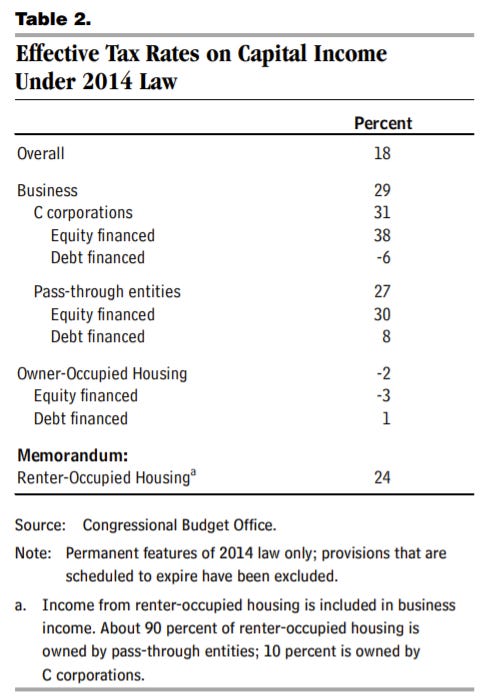

One document from the Congressional Budget Office I’m fond of is a study from 2014 on the effective tax rates on different kinds of investments. Owner-occupied housing is close to zero, because the biggest benefit it gives you is completely untaxed.

It is worth examining how housing stacks up to the alternatives. The tax rate on C corporations (the type of business you might buy stock in) is 31 percent overall, after you consider the entity-level taxes paid by the corporation as well as the personal-level taxes paid by many shareholders. So if you’re looking at things from the perspective of capital to spend on either a down payment or a stock portfolio, it is likely that the down payment’s returns will be taxed less.

You can also compare the taxation of a renter-occupied home to an owner-occupied one. As CBO shows, renter-occupied housing does have a positive tax rate, primarily because the landlord pays tax on the renter income. Some of the costs of that higher tax burden are passed along to the renter.

Now, there are a variety of tax regimes and a variety of personal situations you could be in. Christian, for example, was writing to us from Germany, where the CBO’s analysis would certainly not apply. This chart is from 2014, so the precise calculations would be different today as a result of the 2017 Republican tax bill. And you might be able to get better-than-average tax treatment on stocks by putting them in a retirement account (though this still doesn’t shield you from entity-level taxes.)

But all in all, the general idea is usually the same across the years, people, and even countries. An owner-occupied home generates income that the tax authorities don’t “see,” and this makes it extraordinarily advantageous.

I have not yet mentioned mortgage interest deductibility, which may surprise some readers. (Christian mentioned this policy in his question.) It is a factor in housing tax policy, but it is not as important as many think. I believe its benefits are so well-known because it is made explicit. There is a line for it on your tax return.

But interest is deductible in a wide variety of investment schemes, so this is less of an advantage for home ownership over other types of investments. And furthermore, it is simply not as large a benefit as the exclusion of imputed rent. The most recent U.S. Treasury estimates put the former at about $30 billion for 2022, and the latter at about $131 billion.

Taxes aren’t the only reason home ownership is preferable in the long run for people committed to staying in place, though. There are also costs to dealing with other people. Some tenants and landlords have bad relationships: tenants damage property, or landlords fail to repair it, or both.

Even if you are not an irresponsible tenant yourself, market rents include, effectively, an “insurance premium” that you might be one. And even if your landlord is diligent about repairing the property, they are likely to impose some limits on how much you can modify it to your choosing. Even a good tenant-landlord relationship has some extra costs and inefficiencies that aren’t present in owner-occupied housing.

The main financial reason to avoid owner-occupancy (and it is a big one) is the high transaction cost of buying or selling. It takes a ton of money to buy or sell a house. This isn’t such a big deal if you live there for five or more years; one-time costs like realtors’ fees and appraisals are not too significant relative to the long-run savings. But if you expect your housing needs to change frequently, it is not worth going through the costly real estate transaction process.

Some strategy games are glorified spreadsheets, and it’s wonderful

Douglas asks: “How excited are you guys for Victoria 3 coming out? Any thoughts on Victoria 2, or Paradox titles more broadly?”

I’m a huge fan of Paradox games generally, and very excited for Victoria 3. I imagine these games are popular with our readers, since they’re often basically glorified spreadsheets for history geeks. But I hope to make an answer interesting even for those who haven’t played them.

Paradox games are generally set in a particular time period on a real world map. The Victoria series, naturally, covers the 19th and early 20th centuries. They tend to be pretty historically accurate as of the start date, but are played dynamically from then on, with the player in charge of a nation (or in the case of the medieval era Crusader Kings games, a dynasty) and making the choices.

One thing I like about these games is that they each have different points of emphasis that are appropriate to their eras. For example, Crusader Kings focuses on the politics of vassals, lieges, and succession, while Hearts of Iron (the World War II-era game) focuses on combat and military logistics, and Victoria focuses on industrialization and great power relationships.

Ideally, you have game mechanics that are evocative of how people behaved or thought at the time. For example, in Victoria 2, one component I liked was the “crisis” system. Certain areas of the world would be flashpoints (for example, because they were ruled by a different ethnic group than the majority population in the province) and start international incidents. Great powers near those areas of the world would actually have to weigh in on the crisis, or otherwise lose “prestige,” which is a real resource that genuinely matters for gameplay. So they become busybodies and take a side in the argument.

Then, as the sides recruit members, it might be clear that one or the other has more military might on its side. This can force a humiliating climbdown, where the side that concedes loses even more prestige—or neither side can capitulate, leading to war.

Perhaps this seems like a stupid way to behave—and it often was in real life—but it’s neat that a World War I-era game gives you the incentive structure to act exactly like a World War I-era power did, and sometimes have it blow up in your face the same way it did for them.

The place where I think Victoria 3 can most improve on its predecessor is by figuring out a better way to model different economic policy regimes.

The basic problem with a lot of resource management games is that a really smart human player never wants to delegate any decision-making because they’re far smarter than the AI. This can lead to tedium, or worse, anti-thematic results. Victoria 2 had “capitalist” characters within your empire who might fund railroad or factory projects. But the capitalists weren’t nearly as smart as the human player, so the ideal choice for a lot of people was to move to greater state control of industry—for example, by picking a reactionary or communist government rather than a liberal capitalist one.

This is, of course, the opposite of what the game set in the era should evoke. Victoria 2 chronicles an era where decentralized decision making and competition turned the U.S. into an economic powerhouse. But if you try to play a historical U.S. that lets the industrialists make their own decisions, you’ll be bound to yell at them in exasperation for all the bad decisions they make.

Capital taxation and saving the golden geese

Scott Greenberg asks: do you agree with Abel (2007) that the best tax system would have a 0% tax rate on labor income and a very high tax rate on supernormal capital income? Practically speaking, would this be a good goal for U.S. policymakers?

Scott is a very advanced tax policy reader, but let me try to talk about this in a way everyone can understand. I’ll give the answer up front, though: I agree in theory but not in practice. And I expect Abel himself would agree. He’s making a theoretical point, not a real-life policy proposal.

So what’s the theoretical idea? In short, it’s about taxes “killing the golden goose.” Economists all agree that wealth accumulation makes a society richer; as you build structures, businesses, or institutions that last for the long run, they earn returns.

The question is whether, or how, you can tax those returns without dissuading people from creating the valuable investments in the first place.

A series of papers from the 80s argued this was a big effect. If people can look ahead and see that you’re going to tax their returns, they don’t invest in productivity-enhancing capital goods in the first place. Then you end up with less prosperity in the long run. Therefore, the argument goes, you shouldn’t tax capital at all.

But Abel says not so fast. There are two types of capital that can’t be dissuaded from existing, even with taxes.

First, there’s capital that already exists, like land or buildings that have already been built or music albums that have already been recorded. A capital tax can raise revenue from these without fear that they would disappear.

Second, there are prospective capital investments that are so obviously valuable that a positive tax burden on them won’t change anything. For example, consider Frozen II, which made over a billion dollars in revenue at the box office alone, at a cost of a few hundred million dollars. (Hollywood accounting is notoriously fuzzy but exactness is unimportant for our purposes.) You could design a system that would make Frozen II less profitable than it would be without taxes, but nonetheless profitable enough that it’s an easy call to still make it.

Ideally, you’d invent a tax that derives revenue both from past investments and super-profitable ones, but not from marginal ones—the ones that are just on the cusp of being profitable. And it turns out, mathematically, that such a tax exists. You do it by making capital expenditures deductible, and then taxing the returns.

A business school student would note that this perfectly matches free cash flow, which is the number investors care about when making decisions. (I actually attended the school where Abel teaches.) A tax rate of 20 percent, for example, would scale down all your free cash flows by 20 percent—as if you just multiplied the whole financial statement by 0.8 at the end. And of course, an interesting thing about multiplying a number by 0.8 is it will never flip the sign. It can turn a worthy investment into a somewhat less worthy investment, but it will never turn a worthy investment into an unworthy one, or vice versa. For an investment on the cusp of profitability, the tax deductions will be exactly as valuable as the projected future taxes.

Abel proposes this tax, and notes that it does not kill the Golden Goose (and in fact, at least seems not to have any distortions at all.) So you should lean on it for as much of your tax system as you possibly can, and cut labor a break.

So why don’t we use this style of tax exclusively? Because there’s not enough revenue there. For one thing, Abel concedes right in the abstract: it might not raise enough revenue to fund the whole government. The U.S. government in its current form does indeed need a lot of tax revenue, and most income goes to labor, not capital, so you have to have labor taxes too.

The second is more subtle; there’s nothing wrong with toy models of taxes, but eventually you have to consider issues of law and practicality and little imperfections in the way that toy models map to the real world. For example, the IRS has an imperfect ability to distinguish capital income from labor income in smaller or more closely-held businesses. So if you lean heavily on Abel’s capital tax and not labor taxes, there is an incentive for businesses to label capital income as labor income.

The IRS also has an imperfect ability to distinguish domestic capital income from international capital income in many multinational businesses. So if you try to have a really high domestic income tax rate on capital, much domestic capital income will get relabeled as international and you once again lose the revenue.

Even the theoretical effects from the toy model don’t quite always manifest in practice. For example, a business might not be able to deduct all the expenses in the year they’re taken, as Abel specifies, because it might not have any income to offset those deductions.

These problems aren’t massive, by any stretch of the imagination. But they get larger and larger, in a non-linear way, the higher the tax rate is. This is a common pattern in tax policy, and it applies to many different possible sets of policy preferences. The problem with your favorite tax manifests larger and larger the more you rely on it, and this in turn encourages you to eventually move down the list from your favorite taxes, and consider third-best, fourth-best, and fifth-best alternatives to help fill in the gaps, rather than relying on your favorite idea as the workhorse for everything.

If you like mailbag posts and want a question of your own answered, feel free to leave one in the comments here (we'll be looking) or email questions directly to Tim or Alan.