Living standards, quality, and the future of money

Some follow-up thoughts about whether living standards are really rising.

Happy Friday! In this post I have two follow-ups from Wednesday’s big post about rising living standards, as well as an answer to a reader question about the future of monetary policy.

Blueberries: what about quality?

Wednesday’s piece included a chart on the increasing availability of blueberries. My friend David Robinson wrote in to ask about the quality of these blueberries. He’s been going to his local farmers’ market, and he says the blueberries there are much better:

The produce that comes from this place tastes and smells far better than what I am used to from east coast supermarket shelves. Econometrically, one blueberry may be just as good as any other. But gustatorily, there are blueberries and then there are blueberries. And much of the year-round produce turns out to be watery and shelf-stable simulacra of the real deal. It's a similar phenomenon as roses that don't smell like roses any more -- same species, but not really the same product -- shrinkflation as applied to mother nature. Doesn't it seem like something important is either lost or, at the very least, at risk due to an imperfection in how we define and categorize the goods we enjoy in life?

It’s important to think about the right counterfactual here. There’s probably no way for every supermarket to have blueberries as delicious as you can find in the best farmers’ market. So for many consumers, the choice isn’t between an amazing blueberry or an average blueberry—it’s between an average blueberry or no blueberry. Increasing the availability of blueberries in supermarkets doesn’t prevent connoisseurs like David from going to a farmer’s market for the really good stuff.

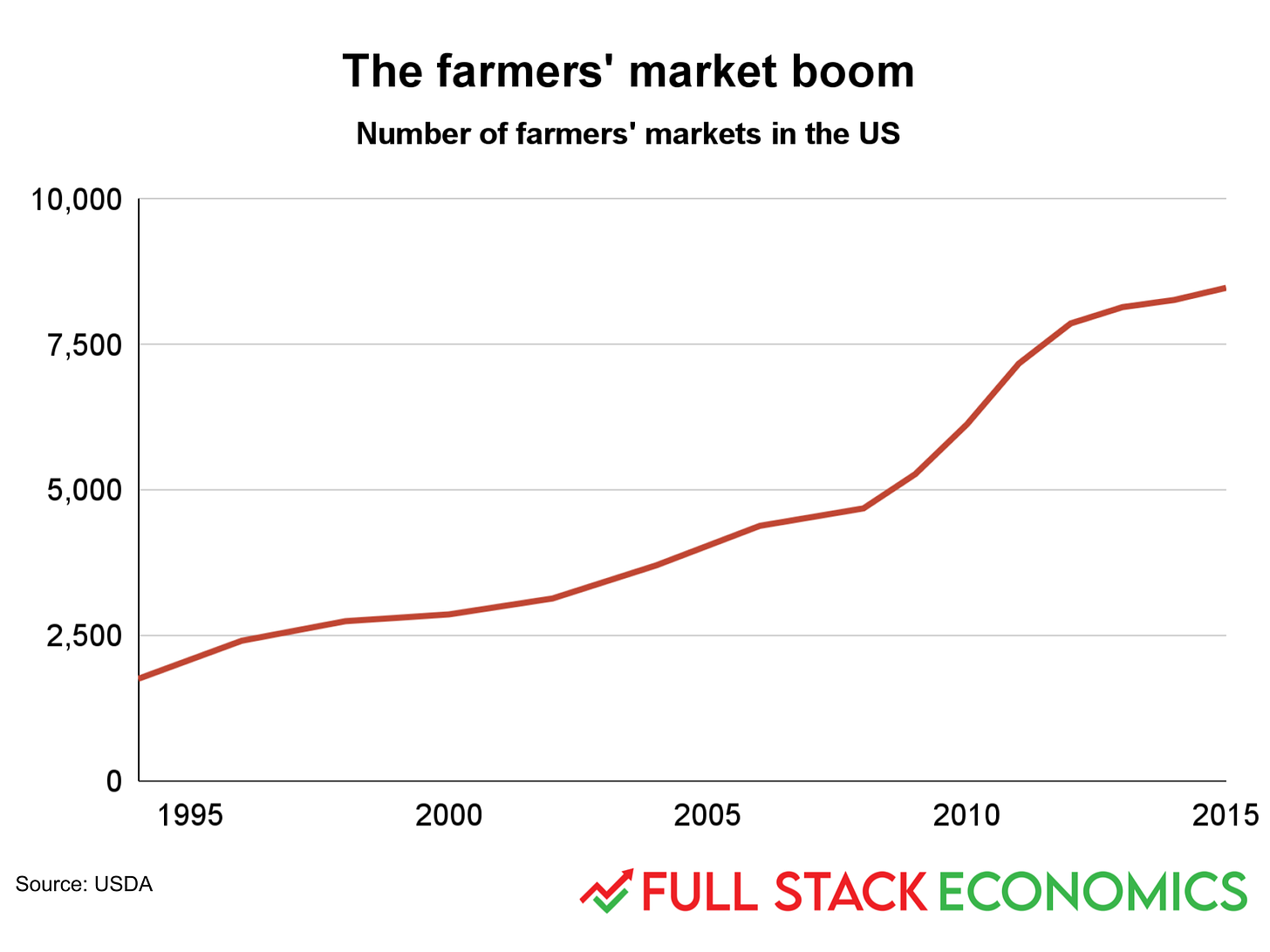

But I do think this tradeoff has been getting better over time. On the one hand, there are a lot more farmer’s markets than there used to be:

On the flip side, I suspect the quality of supermarket produce is improving over time. I wasn’t able to find any data on the deliciousness of supermarket blueberries, but I think apples provide an interesting example.

In the 1990s, the apple market was dominated by the red delicious, which is now widely acknowledged to have not been very delicious. According to the USDA, the red delicious accounted for 42 percent of all apple production in 1996. The Golden Delicious, McIntosh, and Granny Smith were next with 7, 6, and 5 percent market share, respectively. The USDA noted that fuji and gala apples were rapidly gaining market share, growing from less than 2 percent of the market in the early 1990s to 3 and 5 percent, respectively, in 1996.

By 2021, gala apples had risen to 19 percent market share, overtaking the red delicious. Red delicious retained the number two spot, but honeycrisp and fuji apples were close behind.

I suspect it helped that more sophisticated information technology allowed grocery stores to stock a wider variety of products. Because grocery stores stocked more apple varieties in the past, there was an opening for new, more delicious apple varieties to gain a foothold.

I don’t know if this exactly applies to blueberries, since I don’t think they come in as wide a range of varieties as apples do. But I think the broader point is that more sophisticated supply chains mean that consumers have a much wider choice of produce—both within the supermarket and from alternative sources like farmer’s markets. Consumers are likely to be less tolerant of subpar options than in the past. And so I would not be surprised to see the average quality of supermarket fruits improve over time, even if they never quite reach the quality you can get at a farmers’ market.

The Sears catalog: what about quality?

When I tweeted out my chart about the declining cost of manufactured items from the Sears catalog, one of the most common responses was to argue that the quality of manufactured goods has declined over time.

“Washing machines from the 1980s could run for decades and be fixed,” wrote Q-BAS. “Modern ones are disposable after a few years.”

When I was working on the piece I tried to find data on the reliability of cars, home appliances, and so forth and came up short. So I’m genuinely unsure how widely this critique applies.

Some products are clearly better than in the 1980s. Television repair shops used to be common. By 2015, televisions had become cheap and reliable enough that the New York Times declared television repair a “dying art.”

Other products, like hammers and ladders, are unlikely to ever wear out when used by a typical consumer.

But it does seem plausible that some household appliances and kitchen gadgets are less reliable than they were 40 years ago. As manufacturers have fought to cut costs, they’ve often tried to reduce the amount of material in consumer products and replaced expensive materials for cheaper ones.

It’s hard to be sure though. There’s a risk of survivor’s bias: if you bought a washing machine in 1982 and it’s still chugging along in 2022, you’ll tell your friends about it. On the other hand if you bought a washing machine in 1982 and it broke down in 1992, you’ll have long ago forgotten about it.

And even if a 1982 appliance lasted for decades, it wouldn’t necessarily be a good idea to keep using it. Modern washing machines and dishwashers used dramatically less water than the ones we had in the 1990s. Air conditioners have gotten more energy-efficient over time.

Anyway, if anybody knows of data on product reliability over time, I’d love to see it.

Why not a private currency?

Konstantin writes: “Given the market driven nature of much of our economy, it seems surprising that the government is still largely in charge of controlling inflation (which is obviously not going so well right now). Are there ways to regulate inflation and interest rates with markets, rather than having them controlled by the government? This talk by Peter Thiel is one idea that seems like it might work.”

The thing that makes money valuable is that everyone in a particular economy uses it. Your boss pays you dollars, and then you use the dollars to pay your rent, buy groceries, and fill up your gas tank. If everyone around you is using dollars, you are going to want to use dollars too, even if some other option is theoretically superior.

This means that money tends to be extremely sticky—something close to a monopoly. There’s no reason that monopoly necessarily has to be run by the government—you could theoretically have a national currency controlled by a private company. But I’m not sure I’d consider this to be more of a market approach, since this private company wouldn’t face any meaningful competition.

Peter Thiel suggests switching from the dollar to a basket of stocks as our unit of exchange, but I’m not sure how you’d actually do that. I don’t think it would be illegal for somebody to make a smartphone app that makes payments denominated in fractional shares of the S&P 500. But such a project would face a massive chicken-and-egg problem, since you’d have to convince a bunch of people to switch at the same time.

Ultimately, it’s inevitable that some institution is going to control the money supply—and hence interest rates and inflation. I think it’s best to have that institution ultimately accountable to our elected representatives in Congress.

I do think it could be helpful to inject market forces into monetary policy in a different way. I favor having the Fed target the growth of nominal gross domestic product rather than the inflation rate. And the economist Scott Sumner has proposed a slightly zany idea for using market forces to drive monetary policy.

In Sumner’s proposal, the Fed would set up a futures market for NGDP growth and have the Fed conduct monetary policy by buying or selling NGDP futures. In theory, this would greatly reduce the Fed’s discretion of over monetary policy, since the money supply would be directly driven by market forces.

It would be too risky for the Fed to switch to this system any time soon. But a good first step would be for the Fed to set up an official NGDP futures market. The Fed would continue conducting monetary policy in the usual way, but movements of the NGDP futures market would give the Fed another data point to use in its decision-making. A few years later, the Fed could officially switch to an NGDP target, while continuing to conduct monetary policy with its existing tools

If that goes well for another decade or two, perhaps they’d feel comfortable with a more directly market-driven monetary policy regime.