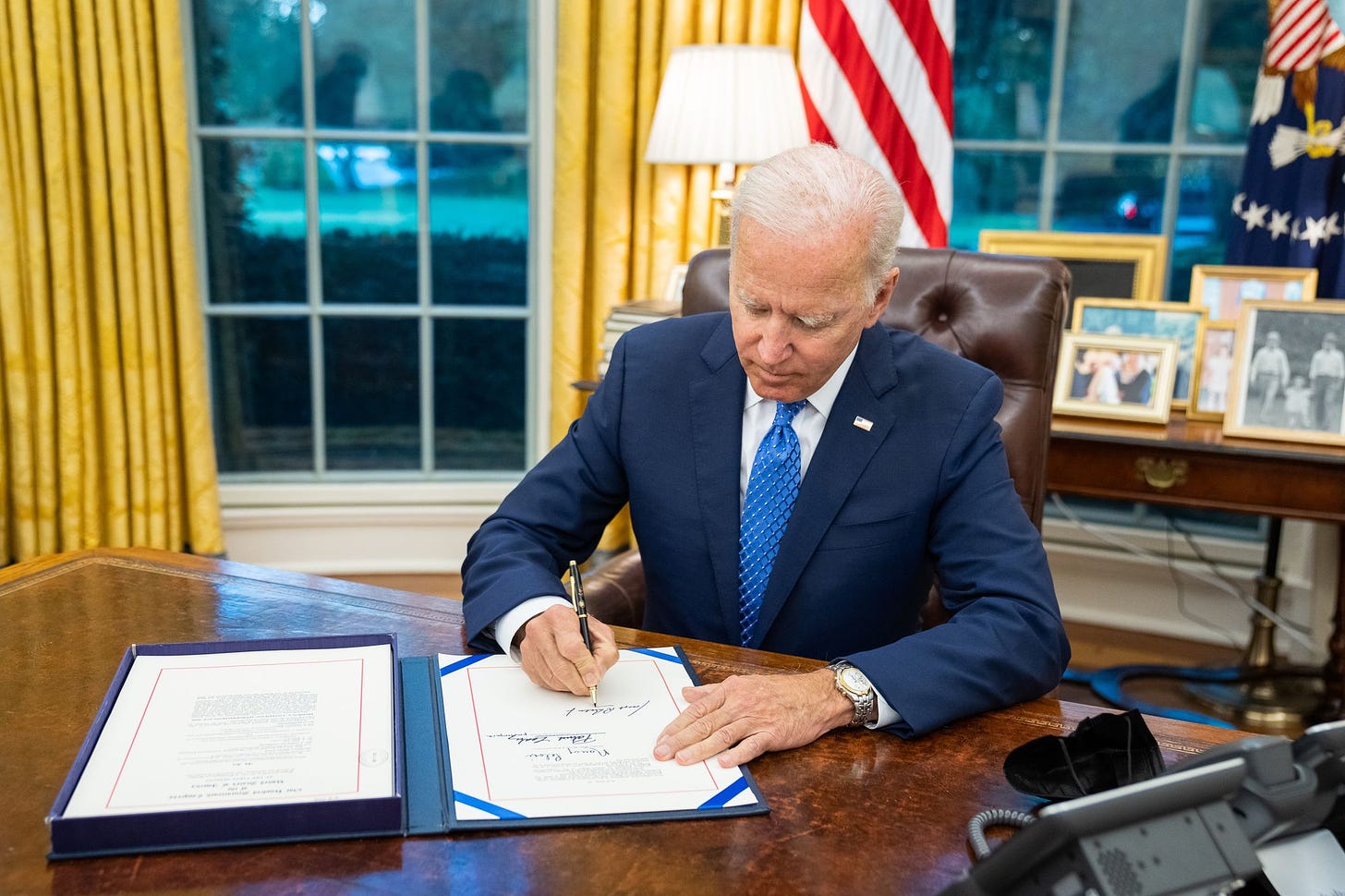

Joe Biden is right to reject loan forgiveness by executive order

Unilateral debt forgiveness is legally dubious and bad public policy.

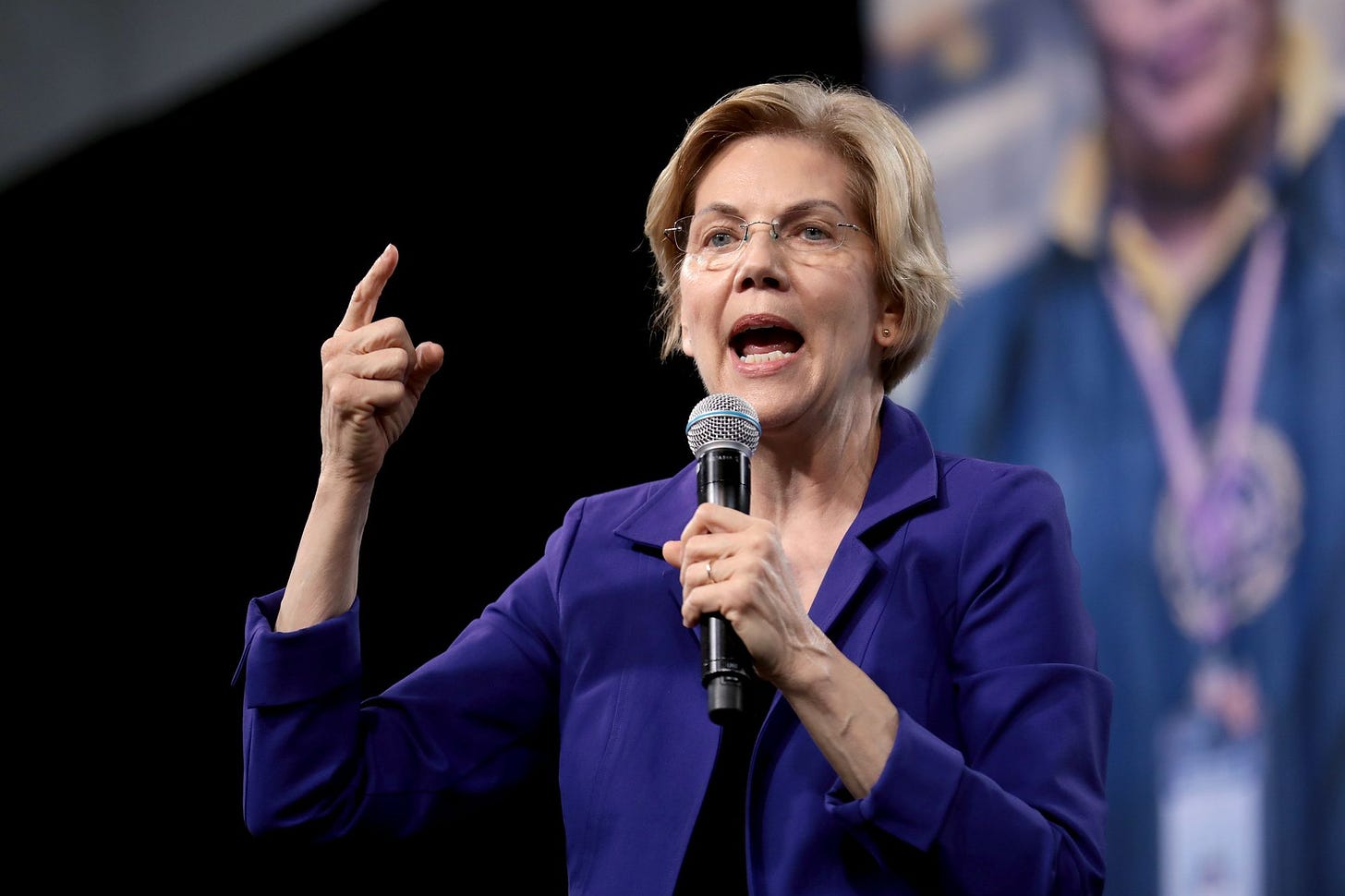

More than 80 Democratic lawmakers, led by Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY), sent President Joe Biden a letter last week calling on him to forgive up to $50,000 per borrower in federal student loan debt. Advocates, including Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), argue Biden has the power to do this by executive order.

The White House has resisted these entreaties. At a press conference last Thursday, spokeswoman Jen Psaki tossed responsibility for the issue back to Congress.

“If Congress sends him a bill to cancel $10,000 in student debt he’d be happy to sign that into law,” Psaki said.

It’s easy to understand why activists are fired up about this issue. Around 45 million Americans carry student loan debt, and it imposes a significant hardship for many of them. But Biden is right to stick to his guns here.

It’s far from clear that Biden has the legal authority for large-scale student debt cancellation by executive order. And a standalone policy of loan forgiveness is bad policy. It would only encourage students to take on more unmanageable debt burdens in the future.

Any program of broad loan forgiveness should be approved by Congress and it should be part of a broader package of reforms to the education finance system.

Warren's plan would be an abuse of presidential authority

The debate over large-scale student debt forgiveness is remarkably new. As recently as the 2016 Democratic primary campaign, even socialist candidate Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) wasn’t calling for outright debt forgiveness; he campaigned on a relatively modest proposal to refinance student loans at lower rates.

Four years later, both Sanders and Elizabeth Warren made debt forgiveness part of their primary campaigns. In January 2020, Warren endorsed the novel legal theory that existing law actually gave the president sweeping power to forgive debts by executive order.

Biden didn’t buy it. On the campaign trail, he supported forgiving up to $10,000 per borrower. But he expressed skepticism that it would be legal to do this without Congress—a position he has maintained in the White House.

So is Warren right that the president—or more precisely the Secretary of Education—can unilaterally cancel anyone’s student debt? It’s hard to say because the idea is so new. Not only have the courts not tested it, there was hardly any legal scholarship on the concept before Warren put it on the political agenda two years ago.

Here’s what we know: the Higher Education Act gives the Secretary of Education the power to “enforce, pay, compromise, waive, or release any right, title, claim, lien, or demand” related to at least some student loans. The terms “compromise, waive, or release” could be read as allowing cancellation.

But critics argue that this kind of over-literal reading of the law makes a mockery of Congressional intent. Congress has established a number of debt-forgiveness programs over the years. In each case, Congress laid out specific criteria for who was eligible for each program and how much debt could be forgiven. It would be odd for Congress to go to all this trouble if the president already had blanket authority to forgive anyone’s debt.

Moreover, the Constitution gives Congress the power to control federal spending and to “dispose of” federal property—including unpaid loans. Congress does sometimes delegate discretion over money matters to the executive branch. But there’s no evidence that Congress intended to grant the Secretary of Education such sweeping authority here. And it would be odd for the courts to hold Congress did so essentially by accident.

Advocates argue it doesn’t matter if Congress intended to give the president broad debt-forgiveness powers. The law says what it says and Biden should use that power while he has the chance. The courts might ultimately rule debt forgiveness illegal, but in their view there’s no harm in trying.

But Biden is right to resist pushing the legal envelope like this. Consider Donald Trump’s 2019 decision to declare a national emergency in order to obtain funding for a wall at the southern border. Federal law gives the president broad discretion to decide what counts as an emergency. And once an emergency has been declared, there are a number of pots of money a president can tap for a project like wall construction.

Trump “has broad leeway to declare an emergency, frankly, whether one exists or not,” one legal scholar told Vox at the time.

But most liberals understood that even if Trump’s actions were consistent with the letter of the law, they clearly went against Congressional intent. At the time, Congress had just pointedly declined to fund Trump’s border wall. And a lack of border wall funding is presumably not the kind of situation Congress had in mind when it gave the president emergency powers.

In a genuine emergency—say a hurricane or the early weeks of a pandemic—it’s useful for the president to have some pots of money he can tap into to deal with problems that come up. But when it grants these powers, Congress trusts the president to exercise good judgment and only use them for genuine emergencies.

If presidents start declaring everything an emergency in order to fund projects Congress won't, Congress will have to curtail the president’s emergency powers. That, in turn, will make it harder for future presidents to respond to genuine emergencies.

At a more basic level, federal money belongs to the public. It's not right for the president to use legal gimmicks to strip Congress—the people's representatives—of their authority to decide how to spend public funds.

A similar point applies to forgiving student loans by executive order. Congress has given the Secretary of Education some discretion over loan forgiveness to allow the government to respond nimbly to unexpected circumstances. But Congress never intended for this discretion to be used to transfer hundreds of billions of dollars to student loan debtors. Under our constitutional system, decisions like this are supposed to be made by the most representative branch of government: Congress.

More broadly, it’s not healthy for presidents to scour the statute books for obscure clauses where Congress may have accidentally given them broad powers. Each time one president does this, it creates a precedent for even more aggressive behavior by the next president. And the line between creative lawyering and outright lawlessness is fuzzy.

Debt relief on its own is bad policy

I’m not going to argue there’s anything wrong with debt relief as a concept. Many people make bad life decisions in their teens, and there is something genuinely troubling about people being shackled with debt decades later.

But large-scale forgiveness without a broader reform of education financing would set a bad precedent. Currently, the federal government gives accredited educational institutions broad discretion to decide what kinds of programs to offer and how much tuition to charge.

In his excellent January piece on student loan forgiveness, Matt Yglesias points to the egregious example of Columbia’s 12-month, $105,510 data journalism program. I am a skeptic of journalism school of any kind, but this seems like a particularly bad deal—not only because of the high tuition but because there are far fewer jobs in data journalism than in the regular kind.

In a world where the government is only providing a modest loan subsidy, it might make sense to take a laissez faire approach and provide subsidies for any programs students want to sign up for. The need to eventually pay off loans should cause students to think long and hard about whether a program is worth the money.

But we’d definitely need to rethink that logic in the wake of a large-scale debt forgiveness program like Schumer and Warren are advocating. Future students would look at a $105,510 tuition bill and think “that’s a lot of money but future presidents will probably forgive a chunk of it.” As more students think this way, student debt burdens will balloon further. It will become impossible for future Democratic presidents to resist calls for additional rounds of debt forgiveness. Taxpayers will wind up footing the bill for a lot of expensive educational programs.

This doesn’t bother a lot of people on the left because they think the government should be funding higher education anyway. But if taxpayers are going to foot the bill, they also need some oversight into the kinds of programs that get funded and how much they cost.

In other words, any student loan forgiveness package needs to be coupled with tighter restrictions on which programs are eligible for student loans in the future. Otherwise, we’re setting ourselves up for an endless cycle of escalating taxpayer costs.

Debt forgiveness should be income-based

Offering debt forgiveness to everyone is a crude way to get help to people who truly need it. My wife, for example, earned a medical degree in 2009 and still has substantial student loan debt. Her medical degree dramatically increased her earning power, which has made it easy to make her loan payments. There is no reason for taxpayers to foot the bill for her.

Back in September, my colleague Alan Cole wrote about income-sharing agreements as an alternative to student loans. The idea is that rather than taking out a loan, students would agree to pay a share of their incomes for a few years after graduating. It’s a theoretically elegant idea but it has a big problem in practice: students who expect to have above-average incomes choose to take out conventional loans. That leaves a pool of under-performing students in the income-sharing pool, causing a downward spiral.

As Alan pointed out, the federal government has long offered income-based repayment options that make federal student loans work a little bit like ISAs. Students who make a lot of money pay back their whole loan. Students who don’t make as much get some of their loans forgiven.So my preferred debt forgiveness plan would be to expand and strengthen income-based repayment plans. Cap peoples’ student loan payments at a fixed percentage of their income (perhaps with slightly higher percentage for graduate and professional schools), and forgive amounts above the cap. A plan like this wouldn't provide a dime of relief to people like my wife who don’t need it. But it would provide relief for people whose degrees didn’t pay off for them financially.

Correction: I originally stated that student loans can't be wiped out in bankruptcy, but that's not quite true. To discharge student loans, a debtor must convince a judge that continuing to pay constitutes an "undue hardship."