I talked to 20 dads who “leaned out” so their wives could be breadwinners

"We realized how much simpler it made our life," one dad told me.

A New Hampshire man named Jan was shooting the breeze with a cop who asked him what he did for a living. He told him that he’s a stay-at-home dad.

“That's what my wife does,” the cop said. “How do you do that?”

“I fulfilled every mother's dream,” Jan said. “I married a doctor.”

Jan and I have a lot in common. His wife is a radiologist. Mine practices obstetrics and gynecology. I’m not a full-time homemaker like Jan, but last month I wrote about my experience “leaning out” to support my wife’s career. I do the bulk of the child care, dishes, and laundry in our household so my wife can focus on practicing medicine.

It’s an unconventional arrangement that works well for us. But after I published my article, a few people on Twitter warned me that I was risking divorce.

New America CEO Anne-Marie Slaughter raised similar worries in her 2016 book about balancing work and family. She cited research finding that female-breadwinner couples tend to have lower marital satisfaction.

I wanted to talk to other heterosexual dads who’d leaned out, so I put out a call on my newsletter. Over the last few weeks, I’ve interviewed 20 leaning-out dads about their experiences.

Many of those experiences are positive. Some are not. I talked to two men who are now separated or divorced from their wives. A few others found child care unrewarding or struggled to get back into the workforce once their kids were older.

Still, I came away from my reporting convinced that this is an option more fathers should consider. Recent research contradicts the idea that female-breadwinner couples are at greater risk of divorce. I think many feminists are too wedded to the ideal of a rigidly equal division of labor within a marriage. I’m sure that works well for some couples. But many other couples will be better off if one does more of the household labor. And dads shouldn’t be afraid of it being them.

“We have this relaxed pace”

One theme I heard over and over again in these interviews was that having one parent lean out simplifies a couple’s life.

“We have this relaxed pace where we can attend to our grandparents and help our friends' kids,” said Adam, a stay-at-home dad in the midwest. “We know a lot of families with two careers. For them it's all chore charts and over-scheduling and barely getting by.”

Adam’s wife, a lawyer, echoed that sentiment. “It’s been really positive for us,” she said. Sometimes male colleagues would half-jokingly ask her how they could get a gig like Adam’s. “I always tell them ‘I'll talk to your wife about how much easier it will make their life.’”

Another dad, Michael, was a data scientist in the D.C. area when his son was born. “Having one person stay at home and be able to take the kids just worked really well for us,” Michael said. “Once I was at home and she was working, we realized how much simpler it made our life.”

“We didn't have to run around and worry about who is going to drop our son off and who is going to pick him up,” he added. “We could see all of our peers struggling with that.”

Another dad told me he appreciates his flexible part-time job on days when school is closed. “If we were both working, it would be a nightmare to figure out what to do,” he said.

Being a self-employed newsletter author lets me play this role in my family. I can watch the kids when school closes or one of them gets sick. That enables my wife to focus on her work and keeps everyone’s blood pressure down.

Not everyone is ambitious

The kind of people who write best-selling books—on this or any other topic—tend to be highly ambitious. Authors like Anne-Marie Slaughter or Lean In author Sheryl Sandberg—or Feminine Mystique author Betty Friedan, for that matter—tend to see it as a big sacrifice for someone to step back from their career for a few years to focus on raising their kids. Because it would be a big sacrifice if they did it.

But this is actually pretty unusual. Lots of people—men as well as women— just want to raise their families and enjoy their lives. I talked to a number of dads who just weren’t very interested in climbing a career ladder.

“I don't have dreams of being in upper management at all,” a software engineer told me. “I just want to keep building stuff.”

He followed his wife to the D.C. area a decade ago so she could take a job in the policy world. When she got pregnant, he quit a demanding job with a long commute to take a nine-to-five job as a government contractor. Since then, he has been responsible for day-care dropoffs and pickups and doctor’s appointments while his wife has focused on her career. She’s now a lobbyist for a technology company and makes twice what he does.

A common stereotype holds that men tend to be more ambitious than women. I don’t know if that’s true on average, but there is undeniably a lot of variation within each sex—and hence plenty of women who are more ambitious or talented than their husbands.

Peter Karadimas, an IT worker who cut back to part-time to focus on child care, told me it was clear that his wife “was the right person to go to work. She was more fulfilled, she's just better at her job than I am at mine.”

Guys like these don’t see themselves as making a big sacrifice when they focus more on their kids and let their wives focus on their jobs. And as gender norms have shifted, it’s gotten easier for dads to make this choice.

Surprise, not hostility

There’s a widespread perception that men who lean out face stigma from friends and family, but I had trouble finding anyone who had experienced that. There are still lingering sexist attitudes about these issues, but they tend to take the form of surprise or confusion—like Jan’s encounter with the cop—rather than hostility.

Several dads said schools tend to call their wives first about issues with their kids—even if the dad lists himself as the primary contact on school forms.

Karadimas told me that while he’s never faced criticism for his decision to focus on raising his kids, some people seemed surprised by the concept of a male homemaker.

“We've never had anything but positive feedback,” Karadimas’s wife told me. She added that “so many women are shocked that my husband would be open to it and even more so that he's good at it.”

“You get this incredulous laugh once in a while that you wouldn't get if you were a woman,” said the conservative writer Robert VerBruggen, who spent 18 months as a stay-at-home dad when his kids were little.

Another conservative writer, Patrick Brown, started leaning out while he was in grad school at Princeton. More recently, he followed his wife to South Carolina so she could take a job as a professor. He said there was a noticeable difference in attitudes between north and south.

“Princeton was very understanding of the situation and gave me time off,” Brown said. “The dean treated me a little bit like the Rosa Parks of gender integration. He said, ‘I don't think we've ever had a man take time off for family reasons before.’”

People in New Jersey were overwhelmingly positive about his choice, but Brown still detected a hint of condescension. “People would say ‘I could never do that,’ and I’d think ‘oh sure you could if you wanted to.’”

South Carolina has been more difficult because it’s rare for dads there to take the lead on child care. “It can be a very isolating form of life if you're at home with young kids and don't have intellectual stimulation,” he said.

The risk of divorce is greatly exaggerated

About a decade ago, a man I’ll call Douglas was an established professional in the United States. He agreed to move to France so his European-born wife could take a job as a professor. He was then in his early 50s, while she was 15 years younger.

At first, Douglas found their new life in France “tremendously exciting,” but those feelings didn’t last. He was hoping to find work in France, but the language barrier limited his professional opportunities and his career stalled.

“My experience was not a good one,” Douglas told me. “By giving up my professional autonomy and my status as a financial contributor, it created tension in the relationship.”

When his wife got pregnant, Douglas wound up doing most of the child care, which made it even harder for him to get his career back on track.

Disagreements about balancing work and family festered over the next few years. Then COVID struck, and the strict French lockdowns pushed the couple to the breaking point. Douglas and his wife separated about two years ago.

Douglas believes sexist attitudes may have played a role in his marital difficulties. He told me that his wife sometimes “made these emasculating comments like ‘you're not man enough.’” For his part, Douglas felt “enormous pressure” to re-establish his professional identity, and this caused him to resent his wife’s expectations that he do most of the child care.

“It was something we unfortunately didn't talk about really explicitly,” he said. “So she wasn’t sensitive to my struggles to regain my professional identity.”

I spoke to another man who cared for his two kids while his wife pursued an academic career. They divorced when the kids were in middle school. “We grew apart,” he told me.

He doesn’t think his focus on child care—which she supported at the time—directly contributed to the divorce. He believes his ex-wife may have been disappointed that he wasn’t more successful in his professional life. He believes that even without kids, he wouldn’t have been “working crazy long hours and traveling all the time. I put a very high value on having lots of free time when I can do whatever I want.”

So are men who prioritize their families over their careers putting their marriages at risk? I put that question to Rhiannon Miller, a sociologist whose research focuses on this kind of question—and who happened to be married to a Full Stack Economics reader.

“The risk of divorce is not higher in couples where the wife makes more than the husband,” Miller told me. “It was higher in previous cohorts.”

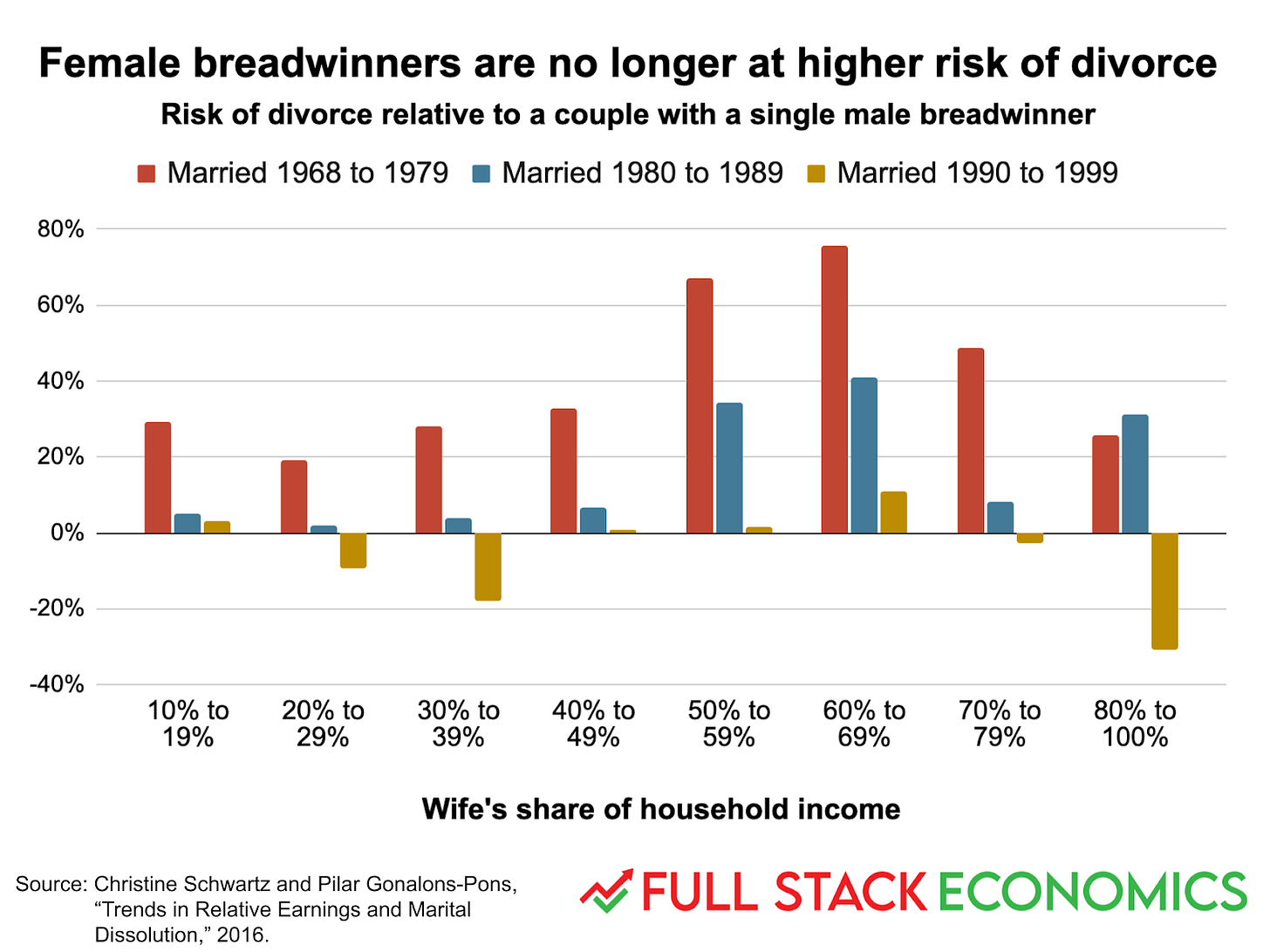

She pointed to a 2016 paper in which sociologists Christine Schwartz and Pilar Gonalons-Pons used survey data to examine divorce rates for couples based on their relative income and when they got married. Their results can be summed up with this chart:

Couples who married in the 1970s were at significantly higher risk of divorce if the wife outearned her husband. The risk was smaller but still significant for couples that wed in the 1980s. For couples married in the 1990s, this effect has almost completely disappeared.

In her book, Anne-Marie Slaughter wrote that friends would show signs of discomfort if her husband mentioned she outearned him. Slaughter, like Douglas, is now in her 60s.

As a 42-year-old man whose wife has outearned him for more than a decade, I can’t identify with Slaughter’s anecdote at all. I’ve never felt embarrassed about my wife earning more than me, and none of the younger dads I talked to expressed discomfort about earning less than their wives.

Adults my age and younger seem to be more egalitarian and pragmatic about this kind of issue. Which means fathers who lean out today are not taking as much of a risk as their fathers or grandfathers might have if they’d made the same choice.

The downsides of leaning out

“I don't particularly relate well to babies,” one father told me. After a few years as a stay-at-home dad, he was growing tired of the experience and started looking for a job. But finding one proved harder than he expected.

“I thought I'd be able to get a job fairly easily,” he told me. A veteran of the Navy, he’s applied for a bunch of civilian government jobs similar to work he’d done during his military service. But employers showed little interest, perhaps scared off by the multi-year gap in his resume. So he’s now using GI Bill benefits to go to graduate school.

Another dad quit a high-paying engineering job in 2018, intending to care for his kids full-time for two years. Then the pandemic hit, and he was effectively forced to continue in his homemaker role for an additional two years. He’s now looking for a job, but hasn’t found one yet.

“Getting back in the workforce is really hard,” he said. “It’s hard to find anybody that is willing to give you an interview.”

Another dad told me that he misses having a conventional job and suffers from a “listless, languishing feeling” much of the time. His wife has a demanding schedule and a high income—so high that it probably wouldn’t make financial sense for her to cut back her hours so he can work more.

Jan, the doctor’s husband in New Hampshire, told me that he struggled in his first few months as a stay-at-home dad.

“I had always perceived my value and worth as tied to my productivity and personal achievements,” he said. “The transition away from that was incredibly hard.”

I think the main lesson here is that fathers (and mothers, for the matter) should strongly consider keeping one foot in the labor market. This could take a variety of forms, depending on the type of work they do. Maybe a dad can cut back his hours rather than quitting altogether. Maybe he can find a job with more schedule flexibility. Maybe he can become a consultant or freelancer or start a lifestyle business.

I’m lucky because this kind of thing is particularly easy to do in journalism. Creating Full Stack Economics allows me to do journalism at my own pace. I’m not making a lot of money so far, but the newsletter keeps my name out there and it will look better on my resume if I want to get a conventional journalism job down the road.

If a dad does make the leap to stay at home full-time, he should be prepared for the possibility that the change could be permanent. Because after a few years at home, he might not be able to get back into his previous line of work.

Communication is also crucial. As we saw in Douglas’s story, it can cause big problems if couples don’t agree about how to balance work and family. Ideally, couples should have in-depth conversations about their needs and desires long before they make a big decision like getting married, having a baby, or moving to a new city.

And even after these big decisions have been made, maintaining regular communication can help prevent minor disagreements from festering and becoming major ones. The good news is that, at least to judge by the latest research, more and more couples may be doing just that.

What you fail to mention, this emancipated-way-of-doing-things is only possible in a small segment the US population. Other people in US society, especially with kids, have to work both to pay rent, utilities, food, clothes. They have no choice who stays home.

And if a choice is made for the wife to lean in more, it is usually because there is a child with disabilities, a sibling needing care, elderly parents needing help, etc. (A lot of work is done unpaid in this area, mostly by women.) Because of many gaps - education, remuneration - the wives usually earn less, making it an "easy" choice.