What's next for Republican efforts against corporate activism

Their quarrel is with management, not shareholders. The policy agenda will reflect that.

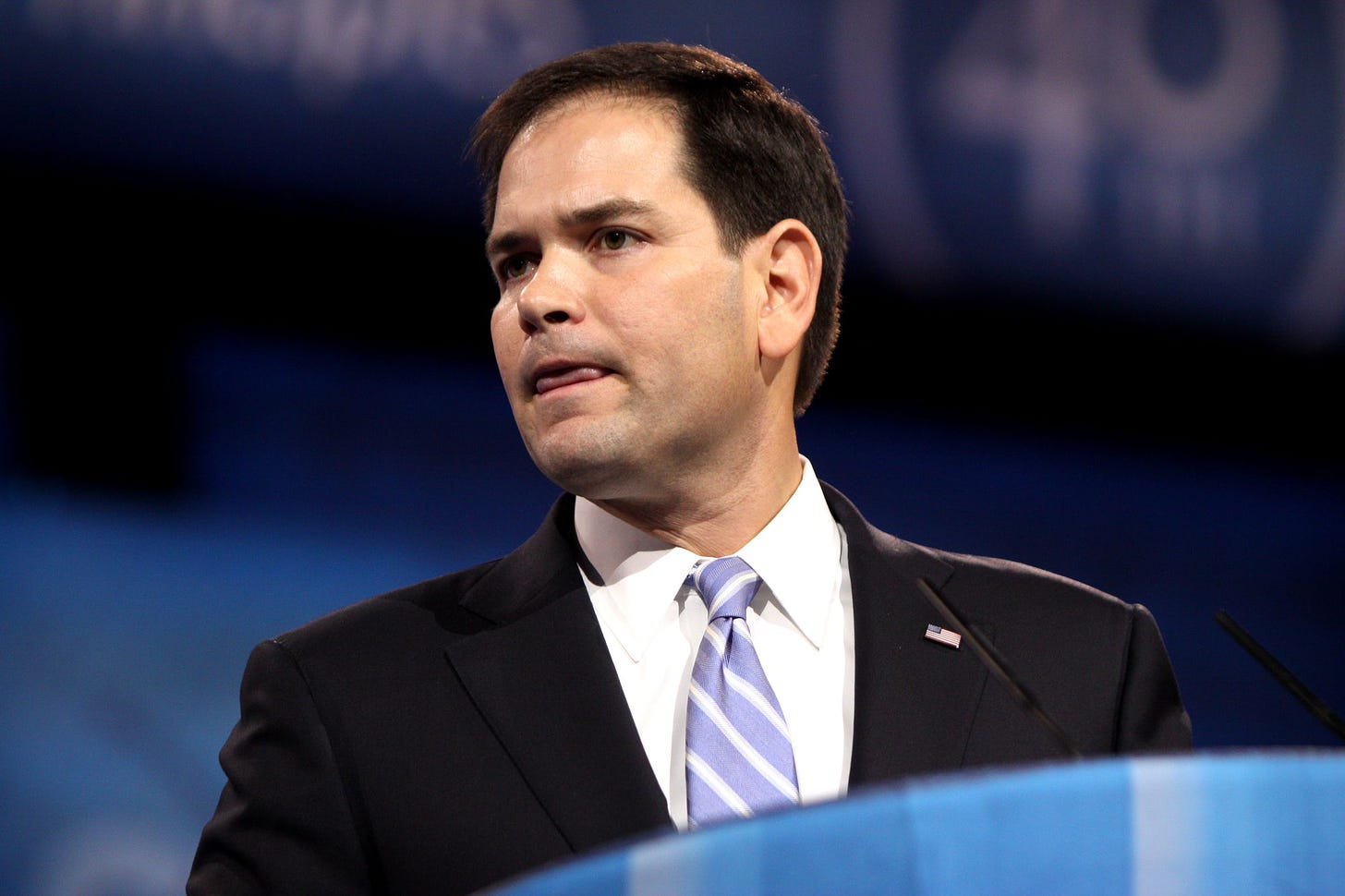

Republican party policy has turned considerably against corporate management over the last two years, largely because of left-of-center corporate activism on social issues. This shift is driven both by relative newcomers like Sen. Josh Hawley (R-MO), and by a change in the posture of longer-tenured politicians like Sen. Marco Rubio (R-FL.)

I covered presidential campaign tax plans in 2015 and 2016, so I clearly remember an earnest Rubio describing on the campaign trail how full expensing of capital investments, a component of his plan, would incentivize more investment, raising productivity per worker and wages. That’s one illustration of Rubio’s broader worldview circa 2016: that business leadership is generally a force for good, and especially so under the right laws.

A fiery Rubio op-ed in the New York Post last year took a dramatically different tone towards business:

These hypocrites want to have it both ways: to coast off everything that makes America the most business-friendly country in the world, while moving good jobs out of our nation and waging a merciless war against traditional values.

And so far, they’ve succeeded. Getting in bed with the Chinese Communist Party has opened up enormous new markets. Outsourcing jobs has been a tremendous cost-saver. Bending a knee to woke progressive craziness has made CEOs more popular than ever in elite settings.

But increasingly, the bill is coming due. More politicians are realizing what I understand: As our corporate leaders care less and less about the strength of our nation, the policy advice they give lawmakers makes less and less sense for our country.

At that time—April 2021—it was still possible to dismiss Rubio’s turn as cheap talk, or an aberration, or the product of a staffing change. (Rubio’s shift in tone was concurrent with his hire of Heritage Action firebrand Michael Needham as Chief of Staff.) Republicans had, after all, voted on partisan lines to reduce corporate tax rates as recently as 2017.

However, since the op-ed was published, Republicans have shown on several occasions that they are willing to fight directly with activist corporations.

In perhaps the most publicized clash between Republicans and business, Disney sharply criticized an education bill signed by Gov. Ron DeSantis (R-FL). The bill would limit discussion of gender and sexuality in school. In turn, DeSantis signed a bill to strip Disney’s unique legal status over the Reedy Creek Improvement District, a special governing jurisdiction for the Walt Disney World Resort.

In the fallout of that same controversy, Senator Hawley, at the federal level, introduced a bill to shorten new copyright terms (which, social controversies aside, happens to be a good idea). But his bill would also retroactively reduce existing copyright terms—but only for the largest entertainment companies. This is a clear shot at Disney, which is explicitly mentioned in the press release.

In another DeSantis clash, the Tampa Bay Rays, a Florida baseball team, used its social media accounts heavily to support gun control efforts, and announced a donation to that effect. Shortly thereafter, DeSantis vetoed $35 million in funding for a spring training site for the Rays. This may again have been a good idea on the merits, independent of social issues; baseball isn’t going to abandon Florida over lack of subsidies. His spokesperson, Christina Pushaw, has insisted that it was a matter of fiscal conservatism. But DeSantis added in a dig that it was “inappropriate to subsidize political activism of a private corporation,” suggesting that the Rays’ social media had played a role.

Below I’ll explain two things. First, why Republicans soured, at least somewhat, on corporations. And second, where corporate activism comes from, and how Republicans are planning to fight it in a more systematic manner than the ad-hoc retaliatory measures described here.

It’s about the summer of 2020

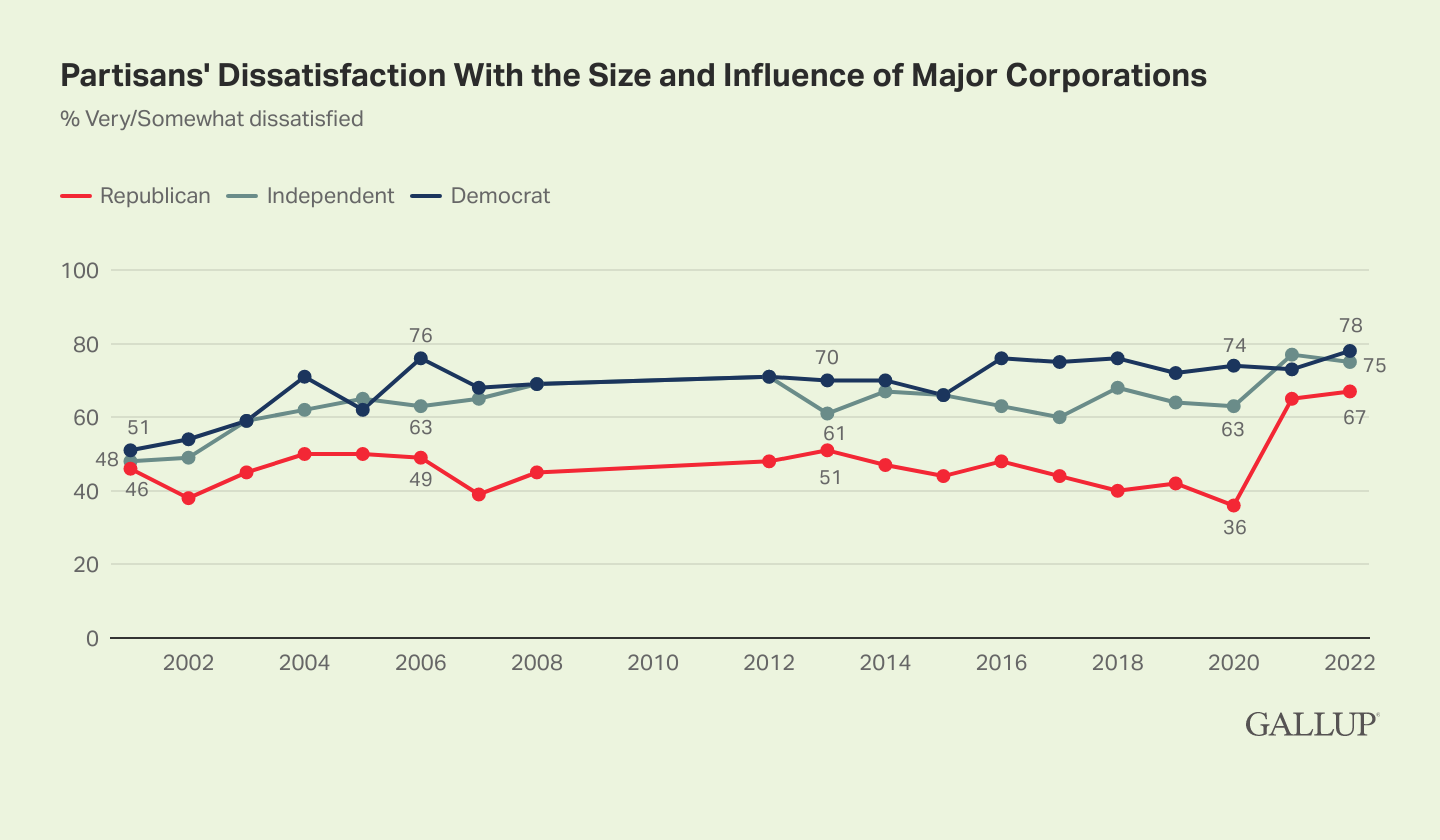

This shift by Republican lawmakers is relatively sudden, and it may be driven by a rapid shift in the views of Republican voters. Gallup shows a 31-point shift among Republicans, over the last two years, on their satisfaction with the “size and influence of major corporations,” with almost all of that shift coming between early 2020 and early 2021.

The largest cause for this change of heart is likely a sequence of 2020 events: the murder of George Floyd, the protests that followed, and the violence that eventually accompanied or followed those protests, which ultimately took at least twenty lives and cost billions of dollars in property damage. This sequence of events was also tied into the COVID-19 pandemic as well; large gatherings had often been prohibited, or at least discouraged, but were suddenly condoned by public figures when it came to a particular favored cause.

Many conservatives’ views on the sequence of events look something like this. From Jordan Boyd at The Federalist:

Despite claims by politicians and corporate media that these protests were “mostly peaceful” and safe to do amidst a pandemic because racism is also a public health crisis, US cities were quickly plagued with looting, violence, arson, vandalism, and damage to public property.

It was this mayhem that proved fatal for some.

Boyd means this literally: by the third day of the protests in Minnesota, a protester (or at least, a man described as such by the prosecutor on his case) lit a pawn shop ablaze, using gasoline as an accelerant, killing a man inside.

The arson death was among the more egregious deaths, but it was far from the only one. One early account from Forbes enumerated 19 deaths in the first two weeks, though these varied in terms of their outrageousness or in terms of how one might apportion blame.

But the Forbes count isn’t complete; it was published on June 8th, and the summer unrest continued to kill. On that day, the Seattle police had just withdrawn from their east precinct building under nightly pressure from protesters. (Later reporting suggested they were worried that an arson would be particularly deadly.) Following the police withdrawal, protesters created a sort of anarchist commune in the middle of the city. The tiny area—just a handful of blocks—suffered four shooting incidents, the last of them fatal.

More generally, violent crime rose substantially—both relative to earlier in 2020, and relative to prior years—immediately after the protests. Conservatives generally believe this is causally linked, not just coincidence.

The bottom line is that the Floyd protests and their aftermath had a variety of consequences, many of them bad ones. And conservatives were quite attuned to the ill effects.

By contrast, corporations engaged with this moment with unreserved support of the 2020 protests, in some cases to the point of absurdity. The fruit candy Gushers, for example, tweeted “Gushers wouldn’t be Gushers without the Black community and your voices. We’re working with Fruit by the Foot on creating space to amplify that. We see you. We stand with you.”

It's easy to make fun of Gushers, but the overall subject matter was a serious one. To conservatives, it was like public order was collapsing. Police should not be retreating from their precincts and ceding territory to anarchists. It's not a thing that's supposed to happen. And conservatives saw those unambiguous statements of corporate support as if corporations were cheering on the disorder, too, not just the calls for better policework.

There is much to relitigate about 2020, and I don’t intend to do that exhaustively here. (Though I’ll admit, I am at least a little bit curious what kind of Black community-amplifying space Fruit by the Foot ultimately came up with.) The point is simply that conservatives saw it very differently from corporations’ public relations teams.

What’s more, the precedents set in 2020 seemed to pave the way for more corporate commentary on social policy than before. And that commentary—for a variety of reasons—tended to lean left of the median voter. Corporations followed President Joe Biden, for example, in freaking out about voter suppression in Georgia’s 2021 election law, even though the law was about as permissive, if not more so, than the voting laws in many Democratic states. A fair amount of confusion came from claims that were straightforwardly made up. After last month’s 2022 primaries, the Washington Post noted that a record high number of votes was cast, even more than in 2020, “undercutting predictions that the Georgia Election Integrity Act of 2021 would lead to a falloff in voting.”

Somewhere between summer of 2020 and the Georgia kerfuffle, Republican politicians saw the need for plans to fight corporate activism. Rubio’s fiery op-ed came a month later.

Republicans will fight management, not shareholders

It’s a little bit strange that corporations seem to offer up well-left-of-center statements on social policy, even as about half the country votes Republican. But if you think about demographics for a bit, this isn’t too hard to understand. The simplest explanation is that Republicans tend to win among retirees and lose among working-age people. (Exit polls suggest this happened in 2020.) So businesses are likely staffed by a Democratic majority.

There are some additional reinforcing factors. High-education workers, the sort who might become managers with decision-making power, tend to be more culturally liberal than workers overall. Furthermore, “creatives” who might run social media accounts tend to be more culturally liberal still than typical workers.

There are a few consumer-based explanations as well; all else equal, advertisers tend to pursue younger (and therefore, incidentally, more left-leaning) people more heavily than older people. They have the potential to be brand-loyal for much longer, and they may have fewer pre-existing brand preferences. And a final explanation I find relatively convincing is that the left simply cares more about activism than the right does.

In a piece for Insider, Josh Barro lays it out well. In Barro’s telling, “woke capital,” a term popularized by the New York Times’ Ross Douthat, is a misnomer, because woke capital isn’t capital at all. It’s a form of labor. In truth, capital is shareholders. And shareholders, if anything, lean conservative, because they are older than average. Barro concludes that the GOP can remain pro-capital and anti-”woke capital,” simultaneously, without contradiction, because their real problem is with management.

While the ad-hoc retaliatory approach to “woke capital” taken by Republicans like DeSantis has been somewhat successful so far, it comes with costs. Ad-hoc retaliation, especially in an extreme or easily provable form, may be unconstitutional, as first amendment scholar David French says here. French argues that even if a government typically has the power to change policy—for example, creating or revoking the Reedy Creek Improvement District—it cannot change that policy because of protected speech.

In practice, this might be hard to prove; but at least some of these retaliatory policies have been far from subtle. And what’s more, consistent high-profile fights with business leaders may damage Republican fundraising efforts, even if the retaliatory bills survive constitutional muster.

In the longer run, Republicans would need a more systematic strategy to avoid those constitutional concerns—one built around generally applicable laws. Consider the following:

A variety of Republicans, from former vice president Mike Pence to Arizona attorney general and senate candidate Mark Brnovich have taken aim at the “environmental, social, and governance” (ESG) movement led by large asset managers. The idea of ESG generally is that business should engage in more “socially-conscious” behavior, often as seen from a left-of-center perspective. In practice, ESG is extraordinarily nebulous and ill-defined, so it’s hard to know for sure, but Republicans are probably right to think that on average they won’t like the results.

Sen. Dan Sullivan (R-AK) last month introduced the Investor Democracy is Expected (INDEX) Act, which would require large passive investment managers like BlackRock to return their voting interests to individual shareholders. This subtle change in securities law aims to curb the political influence of asset managers.

Senator Rubio has introduced the Mind Your Own Business Act, which would empower shareholders to pursue legal action against corporate management for engaging in activism unless they can prove there was a pecuniary basis for that activism. In the absence of proof that the activism was good for business, shareholders can allege that management breached its fiduciary duty.

What we can glean from this is that Republicans drew similar conclusions to Barro: their issue is with management, not with shareholders. In fact, from shareholders’ perspective, excessively left-wing corporate statements may well be what economists call agency costs. You hire someone (an "agent") to do a job, but they have preferences of their own, and those differ from yours, sometimes to your disadvantage.

Agency costs are everywhere, and we don’t always do something about them. For example, if you’re reading this article during working hours (and it’s not relevant to your job) that’s a bit of an agency cost your employer is bearing. It’s okay, I won’t tell! But for more egregious cases, provisions to limit agency costs can be written into contracts or even laws. For example, you’re definitely not allowed to embezzle from your employer, and if you did that, I probably would tell on you.

It's debatable where you'd draw the line between respecting freedom for the agent and fidelity to the agent's task. But Republicans are thinking about doing more to curb politicking adverse to shareholder interests, and laying the legal groundwork to empower relatively right-leaning shareholders to rein in relatively left-wing management.

One approach to this issue, the INDEX Act, is relatively light touch. A confluence of events, mostly historical accidents, have resulted in a handful of people having an extraordinary amount of voting power over corporate decisions. The INDEX act would try to shift that power back to shareholders.

Here’s how it happened. In the latter half of the 20th century, index funds—stock portfolios with a little bit of each stock, and no active manager—became increasingly popular, because most money managers were unable to justify their high fees. Passive funds offered average returns with minimal fees, and it turned out to be a better deal. Passive funds eventually became multi-trillion-dollar behemoths.

Passive funds are committed to passivity when it comes to trading. But there’s one area in which they aren’t necessarily passive: shareholder votes. It turns out that in addition to the tiny management fee, they also end up with the voting power of their investors.

Nobody really intended this outcome to happen: passive fund investors weren’t investing with BlackRock out of a love for CEO Larry Fink’s proxy voting decisions. They just wanted the returns. And BlackRock didn’t truly have designs on the voting power, it just wanted to eke out pennies on the dollar on a massive number of assets under management.

But BlackRock ended up with that power nonetheless, and in 2021, BlackRock started to “use voting power more aggressively,” in the words of a Wall Street Journal headline. It wasn’t just Republicans who took notice. Charlie Munger, the vice chairman of Berkshire Hathaway and longtime business partner of Warren Buffett, memorably critiqued it this way: “We have a new bunch of emperors, and they’re the people who vote the shares in the index funds. I think the world of Larry Fink, but I’m not sure I want him to be my emperor.” As of 2022, under criticism, BlackRock signaled it would begin to pull back.

There’s a good case to be made for the INDEX Act. It’s not great for a handful of large passive managers to have so much control over the economy, especially given how much of a historical accident that control is.

And pushback on ESG is warranted too. Even if you generally agree socially-conscious investment funds in theory, it falls apart when you get to defining your terms. In Money Stuff, Matt Levine explores some of the consequences; without agreement on what the common good is, many people will sincerely believe each others’ ESG metrics to be fraudulent. Large money managers are ill-equipped to do backdoor politics through finance, and they should probably stop trying.

But I’m more skeptical of the Rubio bill, which is far more expansive. It would empower shareholders very directly against corporate management, and make activism a larger legal liability. It seems like it would deliver conservatives much of what they want. But a world full of shareholder litigation is wasteful, and in practice, the measure is likely to be far less effective than it sounds. Moreover, it would likely need to delegate substantial power to federal regulators, who might have some of the very same left-of-center sensibilities as management.