How Biden’s $400,000 tax pledge hobbles progressive ambitions

The "merely affluent" really are where the money is.

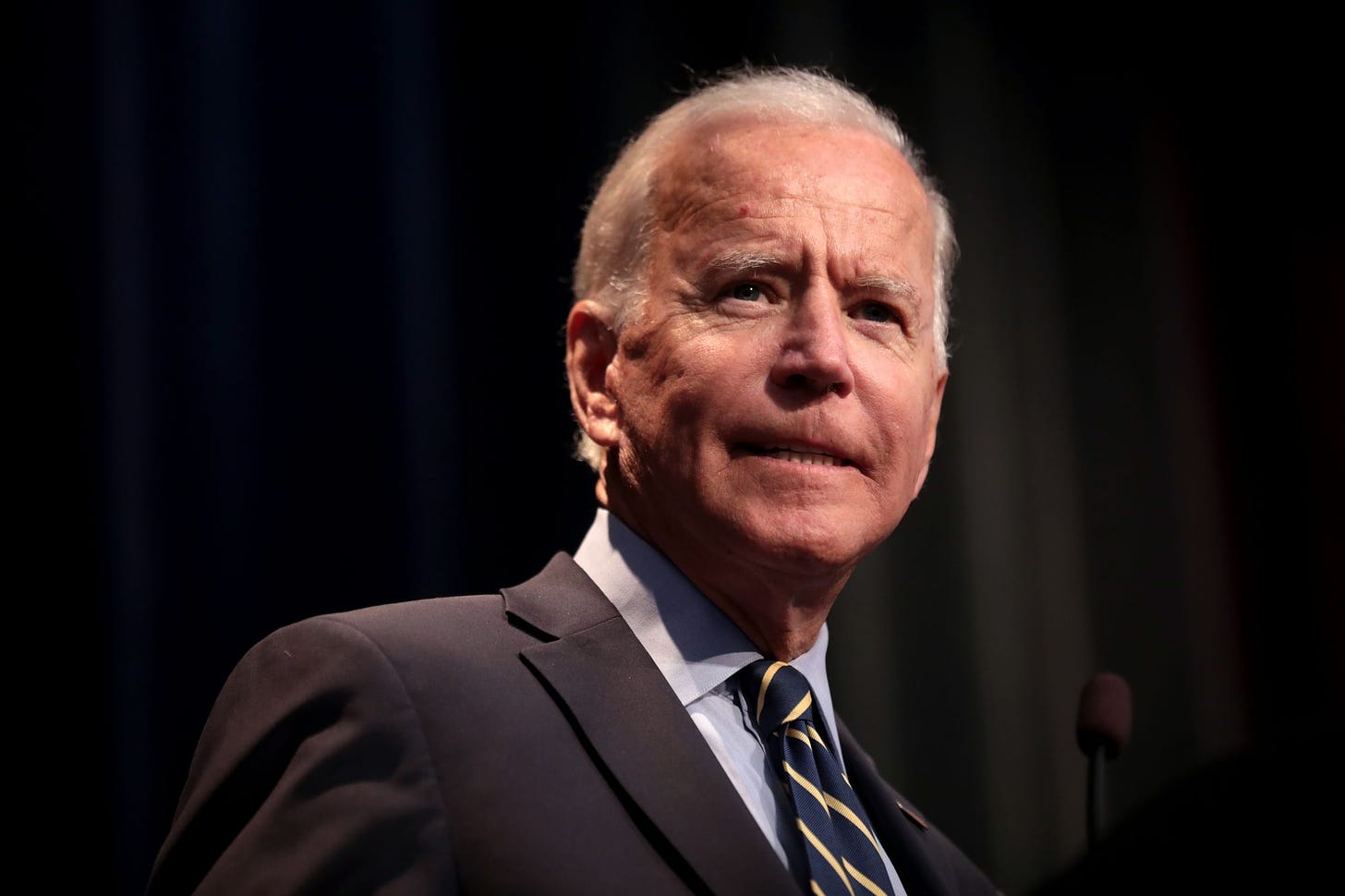

In his 2020 presidential campaign, Joe Biden pledged not to raise taxes on anyone earning less than $400,000 per year. Biden’s promise was more stringent than that of his old boss, Barack Obama, who promised not to tax anyone making less than $250,000.

In an email last week, reader Andrew K asked me to explore how much revenue can actually be generated by raising taxes on the rich. The result is bad news for those who want to dramatically expand the welfare state—though not necessarily for more moderate liberals.

Some quick arithmetic

Some organizations—like my former employer, Tax Foundation—can answer these questions with precision by simulating thousands of tax returns.

But back-of-the-envelope math, while less precise, can be better for instructional purposes because it helps you understand why the numbers are the way they are.

Let’s look at the IRS’s Statistics of Income (SOI) tax tables. Here they publish aggregated statistics of tax returns, sorted by size of adjusted gross income (AGI).

In 2019, there were about 158 million tax returns filed in the U.S. and the SOI tables divide them into several income groups. Unfortunately for our analysis, they draw the line at $500,000, not $400,000, but we can work around this.

Only 1.7 million tax returns—the literal top 1 percent—had an AGI of $500,000 or more. (About 7.3 million had an AGI between $200,000 and $500,000. We’ll come back to these people later and focus on the top 1 percent for now.)

These top-1-percent taxpayers earned a combined $2.5 trillion in AGI. Not bad, but already not enough to pay for the federal budget. (We raise about $4 trillion a year in federal revenues.)

But it gets worse: not all of this AGI is accessible. For example, after deductions, only $2.3 trillion of it is taxable income.

But here’s another way much of that money is off limits. Since income tax brackets build up on top of each other, a pledge not to raise taxes on people earning less than $400,000 a year is effectively a pledge not to raise taxes on anyone’s first $400,000, even if they actually earn more than that. For example, someone who earns $400,001 would only have a single dollar in the above-$400,000 bracket. The “first $400,000” is off limits.

How much of the top one percent’s money constitutes their “first $400,000?” About $680 billion: 1.7 million people multiplied by $400,000. This leaves perhaps just $1.6 trillion left of “above-the-pledge” money.

But wait, it gets worse: much of the above-the-pledge money is already taxed. These people are already paying about 28% of their taxable income, on average. So of the $1.6 trillion of above-the-pledge taxable money, only about $1.2 trillion of it remains untaxed.

Now, let’s come back to the people we missed:

Remember I only looked at people making more than $500,000 a year, not $400,000, due to data limitations. How many people make between $400,000 and $500,000?

SOI data show 7.3 million filers in the $200,000 to $500,000 range, with $2.1 trillion in AGI. But you can see how a $400,000 a year cutoff would exclude most of this income. First, less than a third of them make more than $400,000. (Incomes follow something like what statisticians would call a “power law distribution,” which means that higher numbers are rarer than lower ones. There are more people who make $250,000 than $450,000, for example.)

And then, even among those in the $400,000 to $500,000 range—there are probably fewer than two million—most of them are closer to $400,000 than to $500,000.

You might be able to see why these people don’t materially change the analysis too much: because their “first $400,000” is off limits, and most of their money is in their first $400,000.

Let’s take an educated guess that there are about 2 million filers in the $400,000 to $500,000 range, and they average about $445,000 in income. This adds just $89 billion more worth of “above-the-pledge” annual income, of which perhaps just $70 billion currently goes untaxed.

Adding these numbers for the people we missed back to the initial calculation, we find that there was about $1.7 trillion of above-the-pledge taxable income in 2019, of which about $1.3 trillion went untaxed.

Can these numbers be expanded?

Now if you’re like Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV), or otherwise on the moderate end of the Biden coalition, this number really shouldn’t bother you too much. Raise the effective rate on the “above-the-pledge” money by about ten percentage points, and you get about $200 billion in new revenue a year, enough to fully pay for the more slimmed down versions of Build Back Better that Manchin had been willing to support in talks last year.

But this is far from what progressives really would want. You’d need substantially more revenue to get to the often-quoted $3 trillion per year cost of Medicare for all, for example.

Are there some ways to expand the revenues from the rich? Sure. You could go to higher rates—though at a certain point public opinion turns against this (a lot of people think more than 50%, specifically, is unfair) and you might worry it discourages productive behaviors, or encourages people to hide income. But even at very expansive rates—say, raising effective rates from the 20s to the 50s—you are only going to cover about a quarter of Medicare for All.

You could work to make more AGI taxable, for example, by limiting the deduction for state and local taxes. But of course, a vocal caucus of the Democratic Party, led by representatives like Rep. Josh Gottheimer (D-NJ), wants to expand this deduction for the wealthy, not limit it. In general, itemized deductions are hard to attack, and the Republicans already went for the more politically vulnerable ones in 2017.

The real money is from recognizing more income; for example, by including unrealized capital gains. But a recent Democratic effort to broaden the capital gains tax base failed resoundingly. And that effort—to repeal “step up” in basis and make valuable estates responsible for capital gains tax at death—was far more modest than what I suggested here: including unrealized capital gains in the tax base for millions of people every single year.

A really aggressive attempt to raise money from the top 1% would include all sorts of unrealized gains on things like houses and a projected market value of shares in closely-held businesses. You could absolutely get a larger tax base. But it would be difficult administratively, and controversial.

Social Democracy versus Gottheimerism

The Democratic Party right now has a conflict of sorts, between what you might call Social Democracy or Democratic Socialism—as espoused by Sen. Bernie Sanders (D-VT), and what I’ll call Gottheimerism—the idea that policy essentially cannot do anything to inconvenience a fifth-year big-law associate. As I mentioned above, Gottheimer has famously pushed for the state and local tax deduction the last few years, while showing limited interest in raising taxes for his wealthy New Jersey district.

These two fiscal visions are more or less mathematically incompatible.

Take those who support single-payer healthcare: they often point to Scandinavian countries as the successful real-life implementation of what they want. But as Kyle Pomerleau noted in a post for Tax Foundation, the way Scandinavian countries pay for their spending is not just with high marginal tax rates, but also by having those marginal tax rates kick in for even modestly-above-average incomes—as little as 1.2 times above average. In a provocative analogy, Pomerleau suggests an equivalent of Nordic policy might be to have the top marginal rate in the U.S. apply to all income above $60,000.

But this model conflicts with the material interests of much of the Democrats’ rising base: high-education and, increasingly, high-income voters, many of whom seem to have no interest in such tax increases.

How do Democrats resolve this conflict? For now, it's a split decision: they typically talk like Sanders on social media and during presidential primary season, but act much more like Gottheimer when it’s time to assemble a governing majority.

My own sympathies are more Gottheimerist, but that’s part of a broader worldview skeptical of the efficacy of government. I suspect that many Gottheimerist voters just sincerely don’t know how much they are hampering the Democrats’ fiscal plans.

Viewed from a sort of pop-left-liberal perspective, the pledge seems perfectly reasonable, since of course Everyone Knows that all of the income in the U.S. goes to billionaires.

But in reality, the big-law associates and tech MBAs and pediatricians who drive a lot of Democratic Party discourse are where the real money is, from a tax collector’s perspective. While there’s 1.7 million filers and $2.6 trillion of income in the $500,000-or-more crowd, there’s 31 million filers and $7.6 trillion if you expand that to anyone who makes six figures. The ordinary upscale professionals are simply so much more numerous than billionaires that their combined incomes are much larger.

This is the kind of point that gets you pushback on social media, especially if you characterize a low-six-figure income as “rich” or worthy of more taxation. Richer Americans are more prevalent on Twitter than poorer Americans, and they—like anyone else—are wont to engage in motivated reasoning. They are likely to sincerely believe they aren’t really rich, and that even the more lofty Democratic ambitions can be funded without them.

From the perspective of an earnest, tax-math-oriented social Democrat, the answer is clear: tax six-figure incomes heavily. But from the perspective of a constituent-focused political-math-oriented member of Congress who picks up a wealthy suburban seat for Democrats in 2012 or 2018, you want to run in the opposite direction.

Arguably, the failure of the Build Back Better plan came from this conflict: Biden made a very Gottheimerist pledge, rhetorically cutting off most possible tax revenue, while simultaneously pushing a large spending package and promising to pay for the whole thing. Something had to give.

I will also be answering some smaller mailbag questions this week, but I hope to occasionally answer reader questions with longer responses, as I've done here. Feel free to keep questions coming in the comments or by email. We love hearing from you!