How California plans to turn the screws on NIMBY cities

California is forcing cities to write their own upzoning plans.

Last week California Governor Gavin Newsom signed four separate bills to accelerate housing construction in the Golden State. Individually, none of these bills will transform California’s housing market. But their passage signals how determined the state’s leaders are to solve California’s affordability problem.

Housing projects, in California and elsewhere, frequently face opposition from local activists who have the ear of local government officials. Since the 1970s, the state of California has periodically tried to overrule local governments and allow the construction of more housing. But locals kept finding creative ways to block construction projects. And state legislators—fearful of angering NIMBY activists—never seemed fully committed to the issue.

But attitudes started to shift about five years ago as the state’s affordability problem reached crisis levels. Every year since 2016, the legislature has passed multiple bills to promote housing construction. Every time local governments found new ways to throttle construction, the state legislature has pushed back with another reform package.

“The only way a statewide coalition can force change is iteratively and with repeated efforts,” Yale legal scholar David Schleicher told me on Tuesday. Last week’s legislation, he said, was “one piece in a variety of steps California has taken.”

To better understand the landscape in California, I talked to Laura Foote, executive director of the California-based pro-housing group YIMBY Action.

“There are two parallel theories of how we're going to get the housing we need,” Foote told me in a Wednesday phone interview. One approach is to set statewide minimum zoning standards. An example of this approach is SB 9, which legalizes the construction of duplexes across the state. Governor Newsom signed it last week.

“The other theory is we'll set goals and local jurisdictions have to meet their goals,” Foote says. Under this approach, known as Regional Housing Needs Allocation, the state requires each city to plan for a minimum number of new housing units each year. Cities that don’t do their part face a range of sanctions, from fines to loss of authority over their local planning process.

Experts I talked to expressed greater optimism about this second approach. It’s not going to eliminate local opposition to housing construction, of course. But if it’s done well, it can co-opt local leaders, turning many of them into reluctant partners in raising the state’s housing supply.

California legalized duplexes

SB9 is frequently described as “banning single-family zoning,” but I’m not a fan of this description. SB9 doesn’t ban anything.

Construction of single-family homes will continue to be legal under SB9. Rather, SB9 makes it legal to build a duplex in any location that currently permits the construction of a single-family home. The bill also allows lot splits: if a lot is larger than 2,400 feet, the owner can divide it in half and build a duplex on each of the new, smaller lots.

This reform is likely to be most significant in Silicon Valley, where tech companies like Apple and Google have added tens of thousands of new, highly paid jobs in recent years. Cities like Google’s Mountain View and Apple’s Cupertino have little if any undeveloped land available for construction. And their residential areas are overwhelmingly zoned for single-family homes, leaving little room for new housing. So affluent tech employees have bid up home prices to stratospheric levels: modest bungalows in Cupertino, for example, routinely sell for $2 million to $3 million.

It’s easy to imagine SB9 triggering a modest building boom in a city like Cupertino. A retired Cupertino homeowner could work with a developer to tear down her $2 million home and build two or even four homes in its place. These might sell for close to $2 million each. SB9 requires the owner to occupy one of the new units. The others could be sold to new homeowners, with the developer and homeowner splitting the profits.

While SB9 is a step toward greater housing supply, it remains to be seen how significant it will be. Cities might still find creative ways to stymie use of SB9.

Legalizing ADUs was a long slog

Indeed, that’s exactly what happened over the last decade with accessory dwelling units (ADUs)—small housing units built on the same lot as an existing home. These homes are colloquially known as “granny flats” or “in-law suites” because they’re sometimes used by relatives of the main homeowner. But they can also be rented out—frequently for below-average rents—making them a useful source of affordable housing. Unlike the homes authorized by SB9, an ADU can’t be sold separately.

In the late 20th century, many local governments banned or restricted the construction of ADUs. The California legislature started pushing back as early as 1982, allowing cities to ban ADUs only if they had “specific adverse impacts” on health or safety. But as law professor Christopher Elmendorf explained in a 2019 paper, cities managed to bury ADUs in red tape, including “design review, costly building-materials mandates, rental restrictions, owner-occupancy requirements, minimum lot sizes, conditional use permits, permit-filing fees, impact fees, and tight allowances for the permissible size of an ADU.”

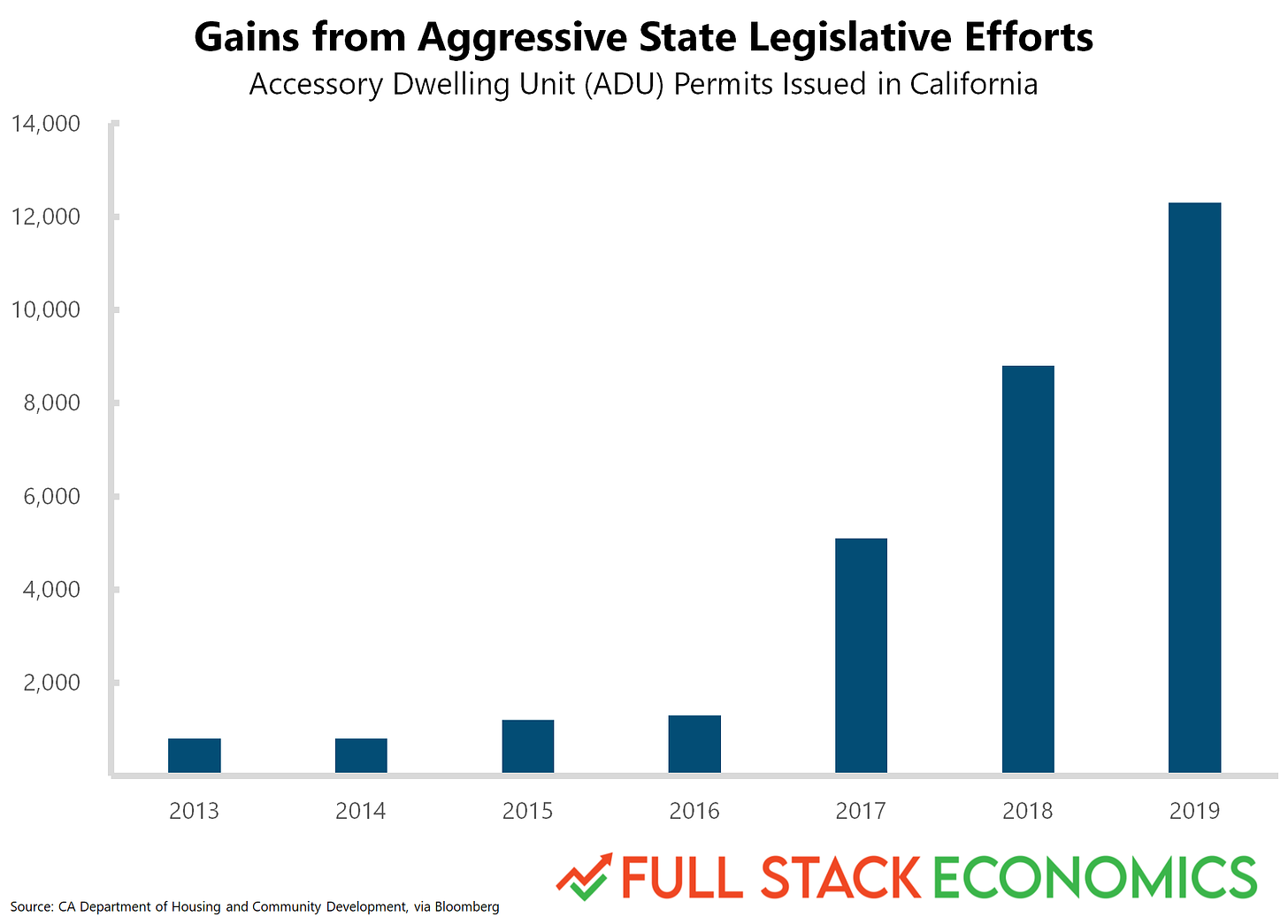

By 2016, the legislature had gotten fed up with these tactics. It passed a series of three bills—in 2016, 2017, and 2019—that progressively weakened local authority over ADUs. According to Elmendorf, the 2019 bill “created an essentially unqualified right for every homeowner in the state to add a freestanding backyard ADU of up to 800 square feet.”

These bills worked as intended. Bloomberg’s Kriston Capps writes that “California homeowners built some 12,000 backyard flats in 2019—more than double the number permitted just two years earlier and a ten-fold increase since the state passed its preemption laws.”

But while the growth rate here is impressive, 12,000 units is still a small number compared to the overall housing need in California. California’s Department of Housing and Community Development estimates that California needs to build 1.8 million homes by 2025 in order to keep up with housing demand.

SB9 would be another modest step toward housing liberalization. An analysis by the Terner Center at UC-Berkeley estimated that there are around 410,000 parcels in the state where it might be economically feasible to use SB9, with a potential yield of 700,000 new housing units. The report’s authors emphasize that this isn’t a forecast for the number of units that will actually get built—it’s more like an upper bound on the number of units that could be built over the next decade or two.

Yale’s David Schleicher is skeptical that SB9 will produce that many units. “Knocking down a house to build two or three units is not easy to do,” he told me on Tuesday. “It's pretty expensive.”

To build truly cheap housing you need the economies of scale that comes from building a bunch of homes at once. SB9 specifically disallows a developer from using its lot-split procedure on adjacent parcels, and doesn’t do anything to help construct larger apartment buildings that could contain cheaper units.

And legalizing larger apartment buildings statewide has proven politically challenging. The YIMBY movement’s biggest failure over the last few years was the defeat of SB 50, a housing reform package that would have allowed for high-density construction in transit corridors. This would have been a more ambitious preemption of local authority than SB9 or the ADU bills. And it freaked a lot of people out. They didn’t like the idea of having large apartment buildings constructed in their neighborhoods without buy-in from local leaders.

Goal-based housing policy

This is where the other major prong of California’s affordable housing agenda comes in. Rather than stripping public officials of authority, this second approach drafts city leaders to help plan for higher density. Many housing advocates believe this process, called the Regional Housing Needs Allocation, has the best potential to boost housing supply in the coming years.

Every eight years, the state government assigns local areas a minimum number of units they must accommodate in their master plans. The state is currently in the process of handing out assignments for the next eight years, with separate targets for low-income, moderate-income, and market-rate housing. Each city must then submit a report detailing where and how it plans to reach these goals.

This basic process has been around for 40 years, but it has only recently been given real teeth. The legislature overhauled the housing needs formula, and as a result goals will be several times higher than they were the last time around. Cities will now be required to submit a detailed, parcel-by-parcel inventory of locations where new housing can be constructed, and developers who rely on this inventory will have remedies if cities try to change their minds later.

Cities that fail to cooperate with this process will face a series of escalating sanctions. If a city falls behind on its housing goals, a developer can bypass the regular approval process. This is what happened in the San Francisco story I wrote about last month: because San Francisco was behind in its goals for affordable housing, a building with enough affordable units could get fast-tracked.

In extreme cases, the state can directly take over the city’s planning functions and write a housing plan for the city. This threat gives intransigent cities a strong incentive to cooperate in the RHNA process.

Pro-housing activist Laura Foote is positively gleeful about the way this will make officials squirm in NIMBY cities like Cupertino and Beverly Hills.

City council members “have to vote to submit a proposal for how to upzone their own city,” she told me in a Wednesday phone interview. “They're going to have a lot of voters that are going to be mad at them for complying with the law.” But the council members “will be like ‘guys if we don't do this it'll be worse.’"

"I'm going to be popping my popcorn every day,” she said with a chuckle.