Some quick econ takes—and your last chance for 20% off!

Bigness is good, greedflation data is suspect, and they did *what* with Winnie the Pooh?

Next week, we’ll start doing subscriber-only posts like this one, which we're calling our "short stack" feature. It will feature a mix of quick takes on the news of the day, answers to reader questions, and pointers to important and interesting economics research. We’re making this one free so you can see what you’ll be missing if you don’t sign up.

Today is also the last day to take advantage of this week’s special deal: $79 for a one-year subscription. That’s 20 percent off our normal rate of $99. Click here to sign up.

Ask us anything

Reader Cactus Insurance asks on Twitter: can the pro-immigration movement use economics to win the argument?

I wouldn’t use any simple supply or demand argument. Those can be turned on their heads, and you ultimately end up debating magnitudes.

More labor supply sounds great to employers and consumers, but immigration opponents can say immigrants are competing with you in your line of work.

Conversely, more demand for goods and services sounds great if you can take advantage of more demand for your work. But at the same time, that means from a consumer’s perspective, immigrants might be competing with you for the goods and services you want to buy, pushing up their prices.

All of these effects are real, and I feel pretty certain they’re a net positive for most Americans. But it’s hard to be persuasive, since it’s so easy to conjure the symmetrical downside to each upside.

I kind of prefer arguing for the virtues of bigness, in a general sense. Matt Yglesias’s One Billion Americans expresses the right directional sentiment. One thing you see a lot studying economics is that a big, liquid market with many buyers and many sellers is just better. You get more competition in common products, and more specialization to niche products. Companies often start in big markets, or try to introduce new products to big markets early, and very often put their biggest headquarters in big markets.

Even if you aren’t involved in the global corporate world directly, it’s still good to be in one of the centers of world commerce where most of the headquarters are, because a lot of money flows through those areas.

The U.S. is of course likely to retain most of the “big economy” advantage pretty strongly no matter what it does. But there is some competition at the margin in Europe and China, and it’s worth retaining our advantages over them, even if just for purely economic reasons.

We always welcome new questions, either by email, on Twitter, or in the comments section below.

What’s new?

The Congressional Budget Office has released its newest set of economic projections. Honestly, this is a truly unenviable task right now. The COVID-19 economy was deeply weird, and the bounceback from it will also be deeply weird. So I’d take some of the farther-out projections, which are notoriously hard, with a grain of salt.

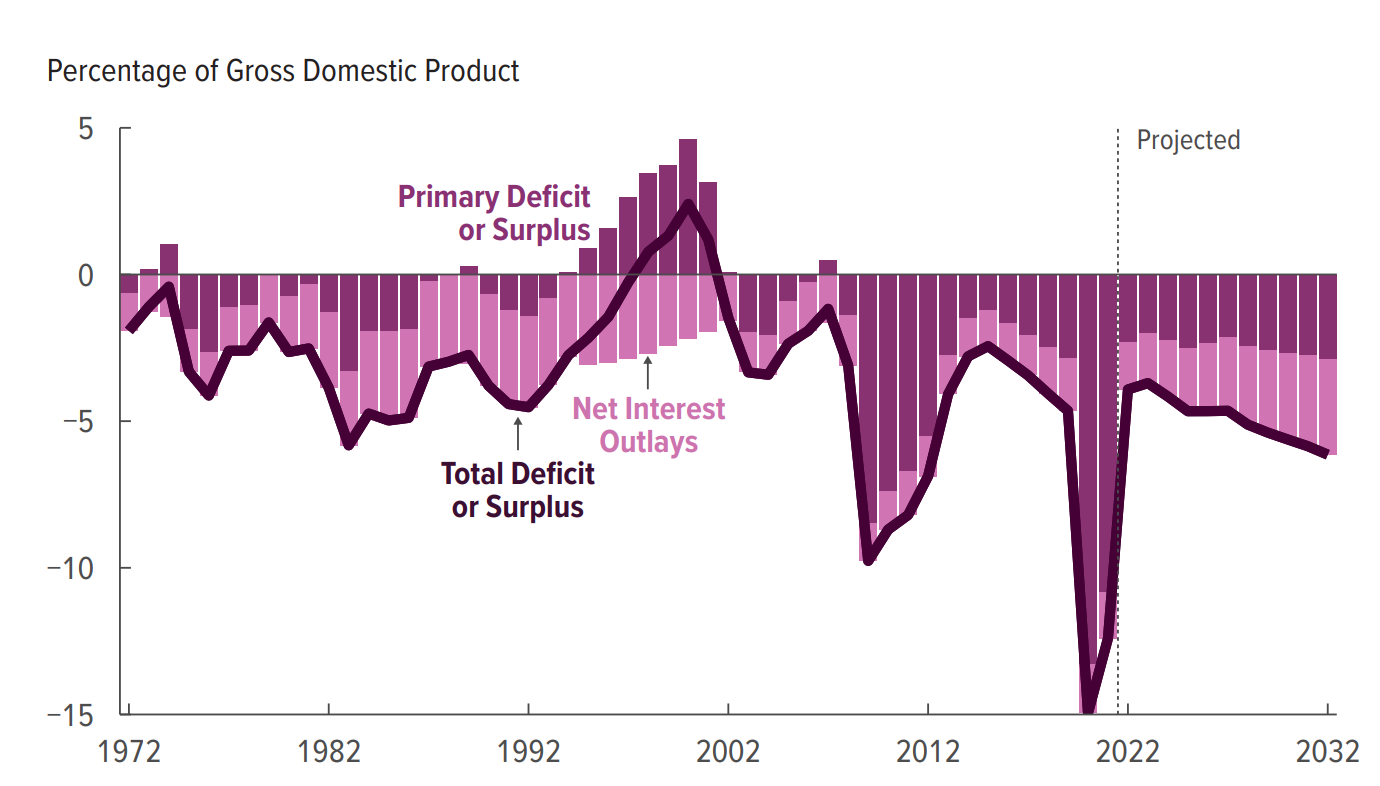

Nonetheless, the big-picture idea to take away is that 2020-2021, between the COVID-19 lockdowns and the fiscal packages by the Trump and Biden administrations, saw by far the largest and fastest increase in peacetime budget deficits. And in 2022 and 2023, we will see the largest and fastest deficit reduction.

It’s very hard to know how much this snapback in fiscal policy will reduce inflation. But it should help. There isn’t as much new spending pouring into the economy, and increased taxes are soaking some of it up.

The recession fears we’ve seen recently come from the possibility that this fiscal drawdown—combined with the Federal Reserve’s rate hikes—is an overreaction.

What’s good online?

Some politicians and academics have pushed a narrative that market concentration (a small number of firms, perhaps colluding) are responsible for worsening today’s inflation. A short policy brief from the Boston Fed lent credence to that view.

At Economic Forces, Brian Albrecht shows that they are using weak data. What’s the problem? They’re using data on publicly-traded companies only. (This isn’t because they’re trying to do a deliberate trick, it’s just easier to find data on publicly-traded companies.) But it’s a fatal flaw.

Brian explains that it’s not just that publicly-traded companies are a fraction of the market (about half.) It’s that they’re a biased fraction of the market, in a statistical sense. The public companies differ from the private companies in important ways.

And unfortunately, they’re not biased in a clear, obvious, consistent way you can control for. Some industries are almost all publicly traded, and some are almost all private, and most are somewhere in between, and the exact reasons for it might vary substantially from industry to industry. So if you look at just the concentration among the public firms, you’re missing part of the picture, and you don’t even really know what part you’re missing.

Albrecht pulls up a damning quotation from a 2008 paper:

Industry concentration measures calculated with Compustat data, which cover only the public firms in an industry, are poor proxies for actual industry concentration. These measures have correlations of only 13% with the corresponding U.S. Census measures, which are based on all public and private firms in an industry.

In other words, academics had determined this data source wasn’t a good concentration measure, long before any of 2022’s “greedflation” debates had begun. And yet, it found its way not only the Boston Fed brief, but also testimony by Hal Singer before the House Committee on Fairness and Growth.

And as pointed out by Harvard’s Jason Furman, the sign of the (relatively weak) correlation actually flips if you use a more comprehensive Census measure of concentration.

It would be easier to just dismiss the “greedflationists” as a rabble-rousing anti-corporate left looking for excuses, or distracting from the problem of excessive demand. But that doesn’t persuade. Instead, Brian addresses the claim seriously, and shows how its advocates haven’t yet done their homework.

What’s dumb online?

Jason Hickel, an economic anthropologist, declares on Twitter:

People often claim that capitalism performed better than socialism in terms of poverty and human development in the 20th century. This story is repeated so frequently that no one ever even bothers to back it up.

Is it true?

This question was explored in a remarkable paper published by the American Journal of Public Health. Using World Bank data, it finds that at any level of development, socialist countries outperformed capitalist countries on key social indicators, in 28 of 30 direct comparisons.

Socialist states had lower infant mortality, lower child death rate, longer life expectancy, better literacy, better secondary education, better food access, more doctors and nurses, and better physical quality of life.

The paper he cites, a 1986 publication from Shirley Cereseto and Howard Waitzkin, is one of the worst papers I’ve ever laid eyes on in my life. It’s actually quite short, at six pages, so if you have a masochistic streak you can read it for yourself. But I can also summarize it for you.

The paper has only two independent variables. The first is whether the authors categorize you as “capitalist” or “socialist” (and here, they mean “socialist” in the Marxist-Leninist sense, not in the way that you might find Danish political parties that raise taxes.) They do this incorrectly, categorizing the People’s Republic of Benin, and Somalia under the Revolutionary Socialist Party as “capitalist.” But that’s the less problematic of the two independent variables.

The second is your level of economic development. Yes, the paper controls for economic development. That is, it measures countries’ performance relative to those that are similarly rich.

There’s an obvious flaw in this method: one of the controls is endogenous, or deeply causally wrapped up in the outcome you care about. If a country raises its income in order to pay for more healthcare, it may end up scoring worse on health because it moves up into a higher category of income and gets its healthcare compared to richer countries. Or if it improves its education, and in so doing, makes its people wealthier, it may score worse on education metrics.

But the paper controls for income, and as a result it pits middle-income communist countries against middle-income capitalist countries, and lower-income communist countries against lower-income capitalist countries, and so forth.

The USSR and much of the Warsaw Pact, for example, are upper-middle-income countries, so it is pitted against upper-middle-income capitalist countries like Uruguay and Mexico and Trinidad and Tobago.

What of the high-income socialist countries? Well, it turns out there aren’t any! Countries like the US and UK and France are in a higher income category than any socialist country, and as a result, it isn’t incumbent on socialist countries to measure up against them in the paper’s regression analysis.

This paper is, as the kids online say, “cope.” The goal of the Marxist-Leninist revolution in the 20th century was not to edge out Trinidad and Tobago on health outcomes. It was to establish a viable alternative to the capitalist systems espoused by countries like the US and the UK. And certainly, Hickel still frames things that way. But look under the hood, and the Marxists quietly defined their goals down.

Odds and Ends

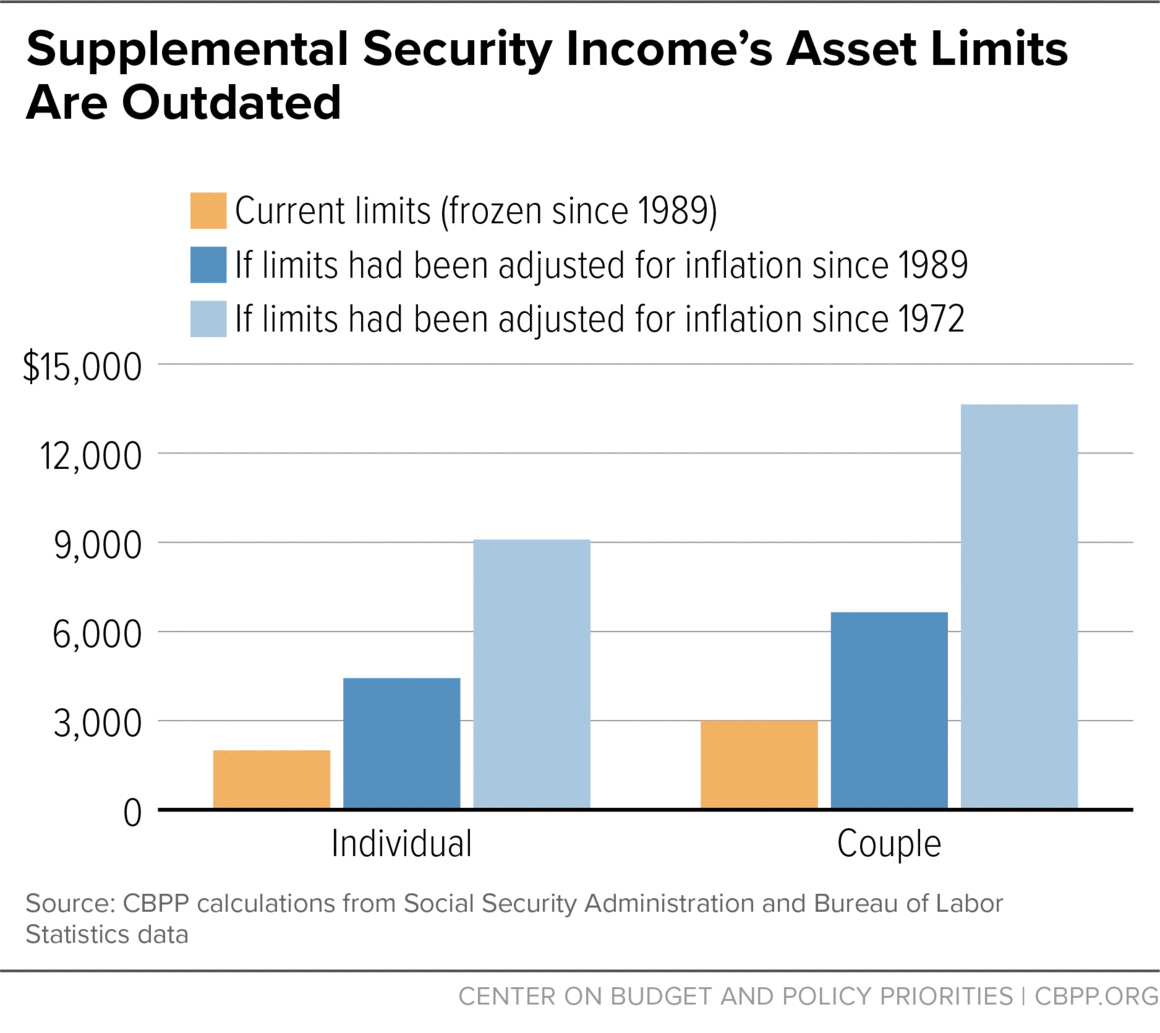

SSI Asset Limits: I wrote last week the asset test on SSI is far too punitive. Kathleen Romig of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities writes similarly, and also has a nice graphic showing how the asset limit would have grown if indexed to inflation.

The Brown-Portman bill, which raises the limit to $10,000 for individuals and $20,000 to couples—gives a full retroactive inflation adjustment, and then some. But that’s a good thing. First, because the limit is probably just not good policy at all, so the fewer people it affects, the better. And second, because even if I accept arguendo that the limit set in 1972 was good at the time, I think it makes more sense as a measure of relative standard of living, not absolute. Since wealth generally outpaced inflation, so too should wealth limits.

Winnie the Pooh—at least, the character from the original book—is now in the public domain, which means people can create derivative works. I argued at the beginning of the year that Pooh should have been free ages ago. Which I stand by. But unfortunately, some of the derivative works—like “Winnie the Pooh: Blood and Honey,” a horror movie in which Winnie the Pooh is evil (I am not making this up!)—seem quite bad. I don’t really advocate shorter copyright terms for the ability to create derivative works like this. It’s instead because I want more children to be able to enjoy the books, and because I want fewer of society’s resources to be devoted to arguing over who owns the rights to what information.

Please click here to subscribe so you can get posts like this in the coming weeks.