Why easy money is (probably) good for ordinary workers

A leftist reporter and a Hayek-loving central banker make a weak case for tight money.

Business reporter Christopher Leonard is on a quixotic mission to make a little-known public servant named Thomas Hoenig a folk hero. In 2010, as president of the Kansas City Federal Reserve Bank, Hoenig cast the lone dissenting vote against quantitative easing, Ben Bernanke’s plan to buy hundreds of billions of dollars of government debt using newly-created money. Hoenig is the star of Leonard’s new book, The Lords of Easy Money. As the name suggests, it’s a polemic against the low interest rate policies of the 2010s.

Leonard and Hoenig make an odd couple, politically speaking.

“I don't make any bones about my leftist political leanings,” Leonard told me in a recent phone interview. “I'm a strong advocate of labor unions.” Leonard’s previous book, Kochland, was an exposé of the Koch Brothers, the billionaire oil barons who have bankrolled libertarian causes for decades (David Koch died in 2019). Yet when Hoenig ended his decades of public service in 2018, he chose to affiliate with the Mercatus Center, a free-market think tank with ties to the Kochs.

Over his long career, Hoenig has demonstrated a stubborn intellectual independence that seems to have won Leonard over. In 2012, after two decades leading the Kansas City Fed, Hoenig became vice chairman of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. In that job, Hoenig waged a lonely battle to break up the nation’s biggest banks. Most Washington insiders considered the issue closed after the passage of the Dodd-Frank legislation in 2010, and Hoenig got no traction.

Hoenig and Leonard see these issues as intimately connected. They believe the Fed’s easy-money policies have benefitted Wall Street insiders at the expense of the general public. Leonard sees Hoenig as one of the few principled dissidents against those policies.

But as Leonard recognizes, this puts him out of step with many economists on the left who believe workers generally benefit from easy money.

“It's been confusing and difficult for me” Leonard said of his disagreement with many left-leaning economists. “I advocate for labor power every day. I'm trying to humbly submit to the court of public opinion that these policies were not good for working people.”

Leonard is a skillful storyteller, and I enjoyed reading his book. But I found its economic analysis wanting. There are a lot of important questions you can answer by talking to ordinary people. But whether low interest rates help workers isn’t that kind of question. To answer this question in a rigorous way you need theories and data. And those are woefully lacking in The Lords of Easy Money.

The Rexnord story

To dramatize the real-world stakes of monetary policy fights, Leonard focuses on the story of Rexnord, a Wisconsin-based manufacturer of ball bearings, conveyor belts, and other industrial equipment.

Before Jerome Powell became chairman of the Fed, he worked at the Carlyle Group, a private equity firm. In 2002, Powell organized a leveraged buyout of Rexnord. Powell and his Carlyle colleagues oversaw Rexnord for four years before selling the company to another private equity firm at a large profit.

Powell got a multimillion-dollar payday, according to Leonard, but “Rexnord itself didn’t fare as well. The company Powell left behind was crippled with debt”—much of it piled onto the company by its private-equity owners.

To illustrate the human costs of these financial maneuvers, Leonard focuses on the life of John Feltner, a machine operator Rexnord hired in 2013. In 2016, Rexnord announced that it was closing Felter’s factory and moving the jobs to Mexico, where workers would earn about $3 per hour.

Leonard argues that the Fed’s easy-money policies drove the behavior of management at Rexnord and many other companies. With interest rates at record lows, it became very tempting to borrow money and pay it out to shareholders. Moreover, Leonard argues that low interest rates drove the expansion of the private equity industry.

Leveraged buyouts predate the Great Recession, but years of near-zero interest rates after 2008 made them more profitable. The private equity industry grew rapidly and more and more American companies became acquisition targets. In many cases, Leonard argues, this turned out badly for workers at those firms.

Leonard makes a convincing case that John Feltner got a raw deal. But his case that low interest rates cost Feltner his job is tenuous.

Low interest rates may have encouraged Rexnord to take on more debt. But Leonard doesn’t demonstrate that this debt was the reason Rexnord closed the factory where Feltner worked. Moving the factory to Mexico was projected to save Rexnord $15 million per year. That would have made it attractive to Rexnord management regardless of how much debt the company had.

Meanwhile, Leonard fails to consider ways monetary policy may have helped Feltner. For example, it’s possible that low interest rates helped Feltner get a job at Rexnord in the first place. The economy wasn’t growing very briskly in 2013, when Feltner was hired, but it was growing. Maybe tighter monetary policy between 2010 to 2013 would have meant a slower recovery or even a double-dip recession, preventing Rexnord from hiring Feltner.

It’s also possible that tight money cost Feltner his job in 2017. The Fed hiked interest rates in December 2015—the first time it had done so in seven years. The New York Times’s Neil Irwin wrote that this contributed to a “mini recession” that occurred in early 2016 and was concentrated in the manufacturing and energy sectors. During this period, the value of the dollar rose, making US exports uncompetitive and outsourcing more attractive. Could weak demand and a strengthening dollar have encouraged Rexnord to outsource its factory to Mexico? I don’t know. But this theory doesn’t seem any less plausible than Leonard’s theory that low interest rates caused Rexnord to move the factory.

Why we need theories, not just anecdotes

I asked Leonard if there was a school of monetary thought that influenced his work. His answer was admirably candid, but I think it also illustrated a fundamental problem with his book.

“I think I am frustratingly inadequate on that point,” Leonard admitted. “I have severe Reporter Brain. I am just obsessively focused on who said what, how decisions got made and how they played out.”

The problem is that without a theory, it’s hard to know how much weight to give to any given anecdote.

For example, it wouldn’t be hard to find examples of workers who benefited from Fed policies during the early 2010s. Here are some hypothetical but plausible examples:

A guy in the construction trades who was able to get more work because low mortgage rates had stimulated home-building.

A woman who got a job at an Ohio Ford plant thanks to an automotive boom spurred by cheap auto loans.

A guy who worked in RV sales doing brisk business as the soaring stock market allowed more affluent retirees to cash out.

Of course, if I found a specific person who fit one of these categories, I wouldn’t be able to prove that Fed policy helped that particular person—any more than Leonard can prove easy money hurt John Feltner. In this respect macroeconomics is a bit like climate science. We know that rising global temperatures make extreme weather more likely, but it’s hard to pinpoint how large-scale trends affect any particular person.

Scientists understand the impacts of greenhouse gas emissions using large-scale quantitative models. Monetary economists do something similar. In both cases, it’s a highly imperfect process, because there’s no way to do controlled experiments.

But while making progress in macroeconomics is difficult, it’s not impossible. And as we’ll see, the best evidence suggests that premature monetary tightening can have disastrous consequences.

While Leonard said he eschewed economic theory in favor of on-the-ground reporting, Hoenig was happy to identify his intellectual influences. In a phone interview, Hoenig told me that his views on monetary policy were influenced by the Austrian school of Ludwig Von Mises and Friedrich Hayek—a perspective that has long had adherents on the political right.

Leonard isn’t a self-described Austrian, but the influence of Austrian ideas—presumably picked up from Hoenig—are obvious in the book. Like Mises, Leonard portrays crashes in 2001 and 2008 as inevitable consequences of easy-money policies that preceded them. Leonard worries that we’re on track for another crash in the coming years.

The ECB learned to keep rates low the hard way

A big puzzle about the 2010s economy is why interest rates were so low. One view holds that this is a deliberate policy of the Federal Reserve and other central banks. Advocates of this view, including Leonard and Hoenig, believe that the Fed has been “artificially” holding rates near zero for most of the last 15 years, and that this has caused increasingly severe distortions over time.

The alternative view—one that I personally find more plausible—is that circumstances have essentially forced central banks to keep rates at record lows. Central banks face a basic tradeoff: if they cut interest rates too low, they’ll get high inflation. If they raise interest rates too high, they’ll raise unemployment and possibly trigger a recession.

What makes this tricky is that an interest rate that indicates tight policy in one decade might indicate loose policy in another. For example, in 1978, short-term interest rates were around 8 percent. In today's economy that would be very tight monetary policy. Yet inflation kept rising in 1979, a sign that interest rates in 1978 weren’t high enough.

In the 2010s, we had the opposite situation. Short-term rates were near zero, which would normally be a sign of easy money. But inflation was low and unemployment was high, suggesting that money might actually have been too tight.

The recent history of Europe sheds some light on this question. Like the Fed, the European Central Bank slashed short-term interest rates in 2008. But in April 2011, the ECB concluded that the worst of the recession was over and it was time to raise interest rates back toward “normal” levels. The ECB raised rates from 1 percent in April 2011 to 1.5 percent in July. This contrasted with the Fed, which not only kept rates near zero but also did a major round of quantitative easing during this time.

This provided something of a natural experiment. If the Fed and ECB were keeping rates “artificially low,” then the Eurozone should have seen few ill effects—and perhaps even benefits—from rate hikes. Instead, the eurozone’s simmering sovereign debt crisis worsened. The Eurozone fell into a double-dip recession. In 2012, the ECB responded by cutting rates again, going all the way down to zero. By 2015, things were bad enough that the ECB launched its own quantitative easing program.

I can’t prove that the 2011 rate hike pushed the Eurozone back into recession. Some experts argue that tight fiscal policy, rather than ECB rate hikes, was the main cause of the double-dip recession. But at a minimum, the ECB leadership clearly believed it had made a mistake, since it reversed its rate hike the next year.

In 2011, the ECB had hawkish leaders who were worried about inflation and anxious to “normalize” interest rates. But when they tried it, they got clear market feedback that they’d made a mistake.

It wasn’t so dramatic, but the Fed’s experience fits the same pattern. In December 2015, the Fed raised interest rates for the first time in seven years. At the time, the Fed said it expected to raise rates several more times over the course of 2016. But in early 2016, the economy under-performed expectations, a sign that the rate hike had been premature. So the Fed waited a full year before raising rates again.

Why are interest rates so low?

If the Fed isn’t responsible for falling interest rates, who is? One theory, explored previously by my colleague Alan Cole, points to changing demographics. As the world’s population ages, there are more older people looking for ways to save wealth and fewer young people looking to borrow money to buy a home or start a business. This has put downward pressure on interest rates around the world.

Matt Klein, a journalist who writes the excellent economics newsletter The Overshoot, prefers to focus on wealth inequality rather than demographics. Wealthier people save more of their incomes, so as the rich have gotten richer the demand for investment assets has gone up. Once again, the result is downward pressure on interest rates.

In any event, this is a global phenomenon. The yield on long-term government bonds in the UK, Germany, France, Japan, and other developed countries are all lower than in the US. Whatever is causing interest rates to fall, it’s not unique to the United States.

When I suggested to Leonard that the Fed might simply be responding to larger economic forces pushing down interest rates, he responded with incredulity.

“Are you telling me that the natural interest rate is zero for seven years?” he asked. “Is there really that much excess savings?” He described the thesis as “a hill to climb.”

But while the low rates of the last 15 years may be historically unprecedented, there’s no theoretical reason to assume that interest rates must be positive. As the world gets older and wealthier, the supply of savings may simply be outstripping demand for loans.

Easy money can have a big upside

Leonard closes his book by looking at the Fed’s response to the 2020 COVID recession. The Fed’s actions in 2020 were bigger and much faster than those of 2008. In a matter of days, the Fed announced plans to backstop almost every form of debt the central bankers could think of.

One of those initiatives, called the Main Street Lending Program, was designed to lend money to small and medium-sized businesses. Leonard notes that it saw little uptake: by the end of 2020 it had only leant around $17 billion, a fraction of the $600 billion the Fed had made available.

But, Leonard writes, “this didn’t mean that the Fed’s bailout programs were ineffective. It’s just that they were effective only for certain people. The real bailout, the successful bailout, was shockingly strong and swift. This was the bailout for people who owned assets. The owners of stock were made entirely whole within about nine months of the pandemic crash. So were the owners of corporate debt.”

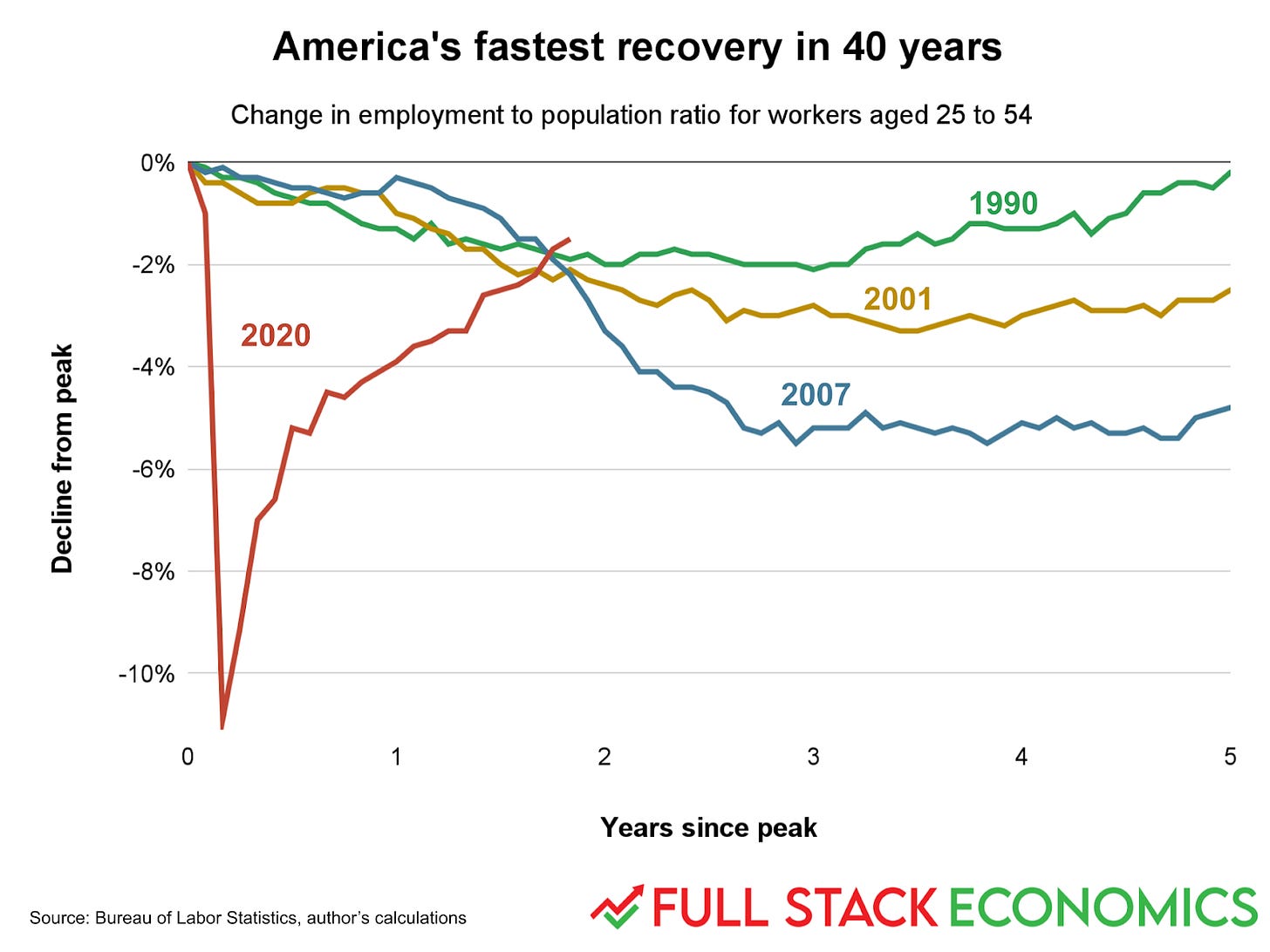

Leonard implies that the Fed’s policies in 2020 didn’t benefit ordinary, non-shareholding Americans. But I don’t think that’s the right conclusion to draw. Take a look at this chart I made for last month’s article “18 charts that explain the American economy”:

This shows the employment rate among workers between the ages of 25 and 54 (economists like to focus on these “prime age” workers because few of them are in school or retired). As you can see, job losses at the start of the COVID recession were far more rapid and severe than in any of the three preceding recessions. But that was followed by an astonishingly fast recovery. We’re on track to return to our previous employment peak before the end of 2022.

Congressional stimulus spending undoubtedly deserves some—perhaps even most—of the credit for this rapid recovery. But the Fed also played a key role by ensuring there wouldn't be a financial panic.

Leonard considers himself an advocate for working people. I would humbly submit that working people have benefited tremendously from the fact that we’ve avoided another prolonged period of high unemployment like the nation suffered from 2008 to 2016.