Cryptocurrency’s regulatory honeymoon is over

Regulators face difficult choices regarding blockchain technologies.

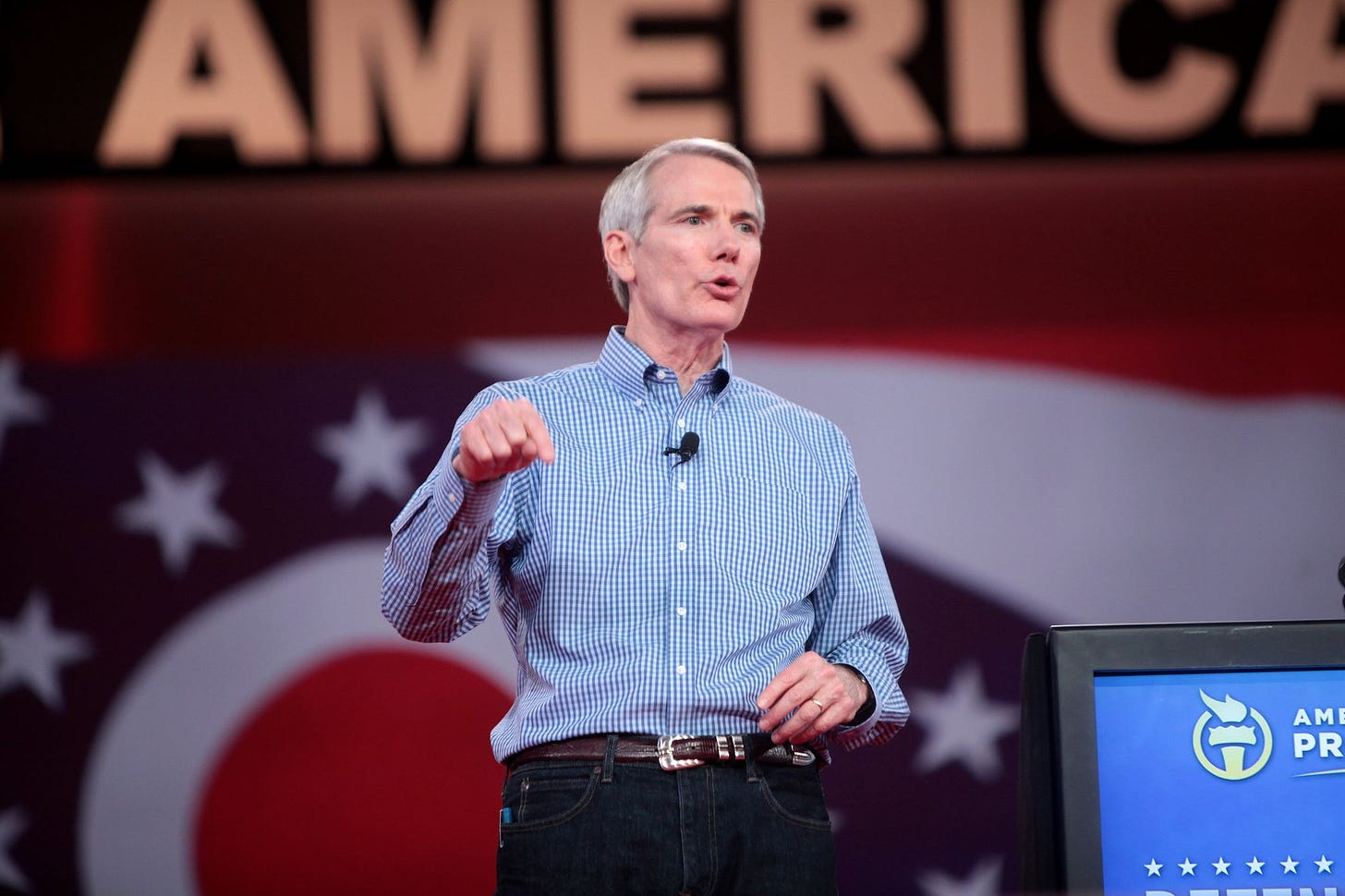

Sen. Rob Portman (R-OH) probably didn’t realize he was sticking his nose in a hornets' nest last month when he proposed new tax reporting requirements for the cryptocurrency industry. Senators were looking for ways to raise additional revenue to offset spending in the $1 trillion infrastructure spending bill the Senate ultimately passed last month.

Portman’s idea was to crack down on cryptocurrency investors who failed to pay taxes on their capital gains. He wanted to require more information to be reported to the IRS, which could generate an estimated $28 billion in tax revenue over 10 years.

The cryptocurrency community responded with fury. They feared that the reporting requirements could be extended to portions of the blockchain industry that lack the resources or information to comply. They were particularly concerned that the rules could ensnare miners, the people who actually process transactions on cryptocurrency networks, and who don’t have the information the IRS needs anyway.

Ultimately, blockchain advocates failed to modify Portman’s proposal or block its inclusion in the Senate bill. But the fight will continue in the next couple of weeks as the House writes its own version of the legislation.

Fights like this are going to pop up more and more in the coming years. For much of the last decade, blockchain technology enjoyed a honeymoon period, much like Uber enjoyed in the early 2010s. Policymakers viewed cryptocurrency as a promising new industry and decided to largely leave it alone.

But as the cryptocurrency sector has grown, the hands-off approach has become increasingly untenable. Blockchain networks are starting to have a big impact on peoples’ lives, and federal agencies will have to decide how to apply a variety of rules—including on tax reporting, money laundering, investor protections, and other issues—to this emerging industry.

They don’t have great options. If they insist that US-based companies in the cryptocurrency industry strictly comply with US regulations, that could put those companies at a competitive disadvantage against cryptocurrency projects that operate outside the US. On the other hand, a continued hands-off posture toward American blockchain companies could give those companies an unfair advantage against conventional financial institutions in the US. It could also allow unchecked growth of problems—like fraud and money laundering—those regulations were written to address.

Bitcoin’s charm offensive

On June 13, 2013, emissaries from the fledgling bitcoin community held some of their first face-to-face meetings with policymakers in Washington DC. Washington insiders didn’t exactly roll out the red carpet. The bitcoiners were in town for a summit co-sponsored by the International Centre for Missing and Exploited Children. A major topic on the agenda was the use of bitcoin to purchase child pornography.

Just weeks earlier, in May 2013, the federal government had shut down a digital currency platform called Liberty Reserve, arguing that it was “designed to help criminals conduct illegal transactions and launder the proceeds of their crimes.” As I noted at the time, the legal arguments used against Liberty Reserve could also have been made against the Bitcoin network.

Bitcoin supporters were hoping to convince DC policymakers not to go down this path. They argued that cryptocurrencies had the potential to be the Next Big Thing in tech and shouldn’t be strangled in their cradle. They also made a more pragmatic argument: that bitcoin’s decentralized structure made the network practically impossible to shut down. It was better to let bitcoin companies stay in the US, where they would at least respond to government subpoenas.

These arguments made an impression on the Obama administration. At a November 2013 Senate hearing, administration officials largely echoed bitcoiners’ arguments and argued that new regulations of bitcoin were unnecessary. Their comments helped allay fears of a regulatory crackdown and attract mainstream support for Bitcoin

An uneasy truce

The feds didn’t completely give up on regulating Bitcoin. Rather, the government offered the blockchain world a de facto bargain: the government will leave core blockchain networks alone in exchange for cooperation at the points where cryptocurrency networks interact with the conventional financial system—the “on ramps and off ramps” of the blockchain world.

For example, federal law requires financial intermediaries to collect information about their customers to aid in the enforcement of anti-money laundering laws. The Obama Administration decided not to apply these laws to bitcoin miners. But the rules were applied to exchanges that help people swap cryptocurrencies for conventional currencies.

The idea was that an American who accepts a bitcoin payment will want to cash it out for US dollars eventually. So as long as the government can identify people who make bitcoin-for-dollar swaps, it has a starting point for investigating crimes related to cryptocurrencies.

But this is an inherently tenuous bargain because the boundaries of the cryptocurrency world are always changing. Newer blockchain networks do more than just facilitate payments. Ethereum, for example, enables the execution of complex financial transactions through a mechanism called smart contracts.

Smart contracts are essentially computer programs that are executed by the Ethereum network and may continue running as long as the Ethereum network exists. People have created smart contracts that enable people to trade one cryptocurrency for another. These decentralized exchanges perform the same job as a conventional exchange, but they’re not controlled by any single person or organization. Once a smart contract is launched, even its creator may not be able to modify it or shut it down.

As decentralized exchanges and other similar technologies mature, the US government’s already tenuous leverage over the blockchain economy might erode even further. For example, one version of the tax reporting provision that circulated on Capitol Hill last month would have specifically required decentralized exchanges to comply with tax reporting rules. If Congress had passed a law like that, it’s not clear how the executive branch would have enforced it.

Some decentralized exchanges simply don’t have anyone with authority to modify them. The only way to change such a smart contract is by changing the Ethereum software itself—which requires a broad consensus of Ethereum miners and developers. Something like that happened once in 2016, when the Ethereum network was only about a year old. But Ethereum has grown a lot since then, and it’s hard to imagine it happening again, especially at the behest of a single government.

Low-hanging fruit

One of Washington’s most influential figures on cryptocurrency issues is Jerry Brito, the executive director of the Coin Center, a pro-blockchain think tank. In an interview with me last month, Brito argued that there was a lot governments could do to improve regulation of cryptocurrency without delving into these thorny questions.

For example, one of the largest cryptocurrency companies, Coinbase, has been saying for years that they’re prepared to submit 1099-B forms to the IRS to report their customers’ gains and losses—the same forms that conventional stock brokers fill out at the end of each year. But Brito says the IRS has yet to issue guidance on how best to do that. He urged the Biden administration to focus on making incremental improvements in areas like this rather than asking Congress for expanded authority.

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) faces a similar situation. Federal law requires anyone who offers an investment product to the public to register the offering with the SEC—a measure intended to improve transparency and deter fraud. In 2016 and 2017, hundreds of people organized “initial coin offerings” without registering. The SEC largely looked the other way as the ICO boom gathered momentum over the course of 2017. Ultimately, ICO promoters raised billions of dollars—much of it from unsophisticated investors for projects that never panned out.

In early 2018, as the ICO bubble was nearing its peak, the SEC’s chairman finally declared that “every ICO I’ve seen is a security.” That implied that hundreds of companies likely broke the law—though the SEC made little effort to stop them at the time. Today, the SEC is still working through a backlog of cases generated by the 2017-18 boom.

The SEC concentrated its early firepower on projects that seemed to be outright frauds, effectively giving a pass to some projects that turned out to be successful. But over the longer term, the SEC is likely to want regulatory power over not just scams but relatively legitimate financial products as well. The agency may find the light-touch approach championed by blockchain advocates like Brito to be insufficient.

Some blockchain platforms are out of regulators’ reach

In recent months Coinbase had been preparing to launch a product called Lend that would pay 4 percent interest to customers based on their holdings of a stablecoin (a cryptocurrency whose value is pegged to the dollar) called USDC. Last week, the SEC notified Coinbase that the program constituted an offering of a security under US law. The agency said Coinbase should not launch the product without first filing paperwork with the SEC.

But as Coinbase CEO Brian Armstrong points out, there are already a number of unregulated platforms that enable customers to earn interest on their cryptocurrency holdings. A lot of them are either based outside the US or are smart contracts that are not “based” anywhere.

The risk for the SEC is that imposing strict regulations on law-abiding companies like Coinbase could drive a lot of this business to platforms that operate beyond the SEC’s reach. That could lead to more US investors being harmed by fraud or a lack of transparency, since overseas blockchain platforms are readily accessible to Americans.

But granting blockchain-oriented companies a de facto exemption from regulations that govern other lending products isn’t a great option either. Conventional financial institutions would be understandably upset if the SEC failed to apply the same standards to their blockchain-based competitors as it did to themselves.

Inability to compromise could lead to a breaking point

This isn’t an entirely unprecedented situation. Again, there are obvious parallels to Uber. A decade ago, Uber openly flouted local laws as the company entered new markets. Uber’s strategy was to grow quickly and then enlist their customers to pressure public officials to change the rules in its favor. This strategy worked remarkably well in the company's early days.

But Uber has become more conciliatory toward local governments in recent years, and it will likely need to compromise further in order to remain in business over the long run.

Uber can make strategic concessions because it is a conventional company with a CEO. Bitcoin and Ethereum are not companies and don’t have anyone in charge. This means the network has no practical way to strike a compromise with any government.

So far, this has largely been an advantage. Early leaders of the bitcoin community could honestly tell government officials that they had no authority to change how the bitcoin network worked. In response, many governments grudgingly accepted that they needed to accept the bitcoin network as it was. It’s possible that this dynamic will continue to exert a deregulatory pressure on the broader financial industry.

But another possibility, at least in theory, is that policymakers reach a breaking point, decide blockchain networks are more trouble than they’re worth, and try to shut them down. That seems to be the path the government of China has been on for the past couple of years.

This seems extremely unlikely to occur in today’s political climate. But I could imagine the politics shifting if there were a crisis involving cryptocurrencies. The US government probably couldn’t stop the Bitcoin network from operating altogether, but it could do a lot to drive it underground—not only in the United States but in allied nations as well.