How policy punishes disabled people who save more than $2,000

The asset restrictions for SSI are so onerous that they are almost literally unbelievable.

Imagine if you deeply feared your bank account going over $2000. Not under. Over.

That would be a weird situation for anyone to be in. But it is the situation that the government has created for recipients of Supplemental Security Income (SSI), who are typically blind or unable to work due to age or a medical condition.

SSI is run by the Social Security Administration (SSA), and it is a basic income of sorts given to some people who have little or no other income. It’s a modest amount—$841 per month for a single person—but actual amounts paid can vary, because some states supplement it, and you get less if you have other sources of income.

It’s not universally available; you couldn’t quit your job and get it, because you’d need to show you have a medical condition preventing you from working for at least a year. About 8 million Americans received it in 2019.

The most important thing for many of these recipients isn’t the checks. Eligibility for SSI qualifies many people for Medicaid. Understandably, people with blindness or a medical condition that prevents them from working are often in need of health insurance.

There are many eligibility requirements for SSI. But perhaps the most onerous is the asset test, which is so preposterous that it has to be read to be believed:

You may be able to get SSI if your resources (the things you own) are worth no more than $2,000 for a person or $3,000 for a married couple living together. We don’t count everything you own when we decide if you can get SSI. For example, we don’t count a house you own if you live in it, and we usually don’t count your car. We do count cash, bank accounts, stocks and bonds.

This isn’t a joke. You really do have to play “hot potato” with your money, never saving more than three months of income (assuming you get the usual benefit) at a time, unless you can divert your money into a category that’s excluded from the SSA’s definition of resources. And if you fail at this, you may well lose your health insurance.

The asset test is so low, in fact, that $2,000 of COVID-19 relief checks around the beginning of 2021 ($600 from the budget deal signed by Donald Trump, and an additional $1,400 from the American Rescue Plan) put people over the limit, all by themselves. SSA clarified that these payments would not count as income, for the purposes of SSA’s calculations. But they would still count as “resources” after a 1-year exclusion period. This meant that at least in theory, recipients needed to keep track of how long ago it had been since each of the COVID-19 relief bills. But not even the SSA necessarily did this right, and some recipients allege that they were excluded improperly.

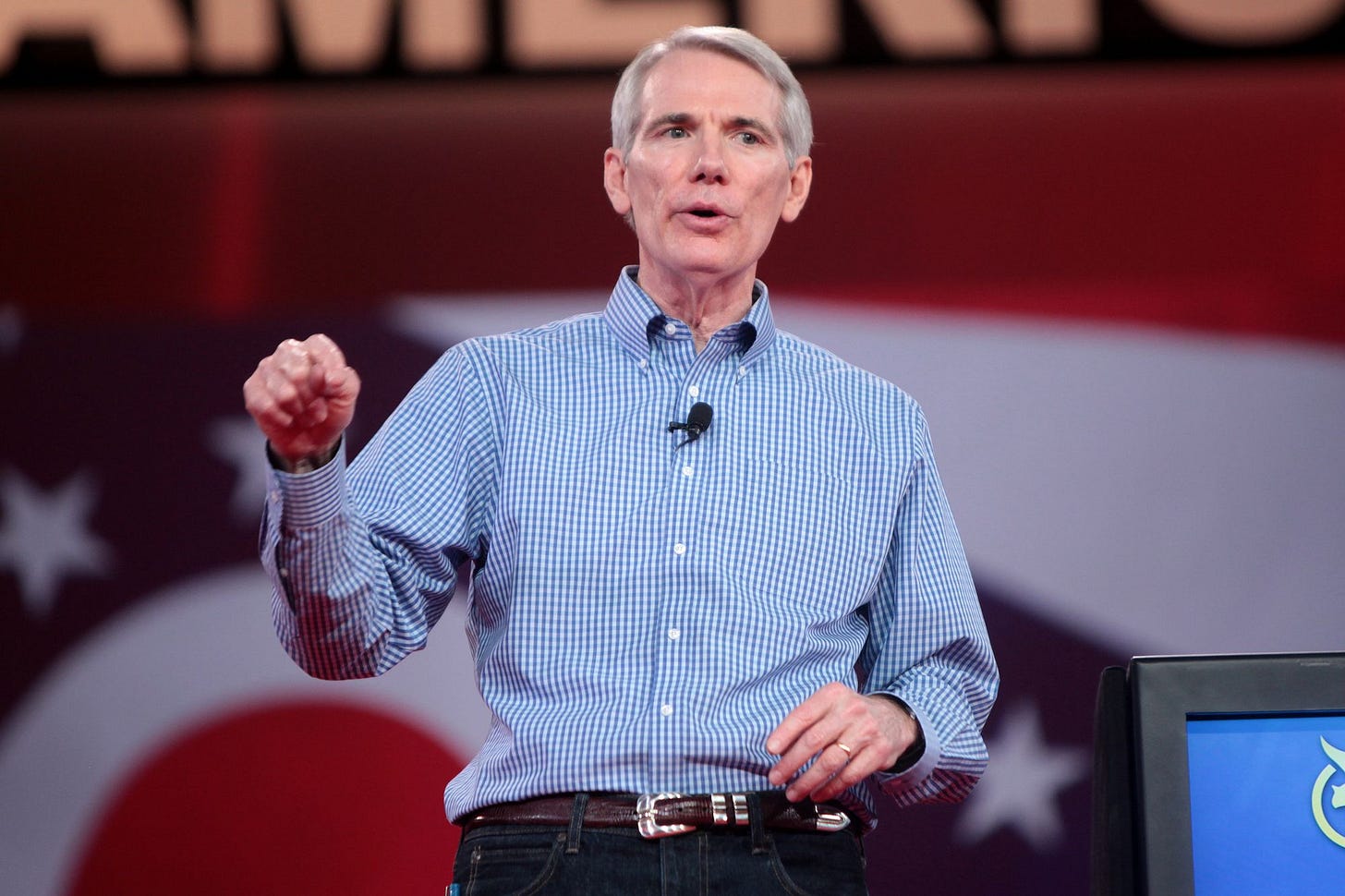

This month, Sherrod Brown (D-OH) and Rob Portman (R-OH) jointly proposed legislation to raise the asset cap to $10,000 (or $20,000 for a married couple).

"We shouldn't be punishing seniors and Ohioans with disabilities who do the right thing and save money for emergencies by taking away the money they rely on to live," Brown said in the press release.

This is the right idea—or at least, the start. Most people, disabled or otherwise, should have much more than $2,000 on hand, to deal with unexpected expenses. And even beyond emergency saving, long-run savings are valuable too. If invested, they can earn a return. This not only increases your income, it also illustrates the useful life lesson that sometimes a sacrifice today can result in greater gains later.

In short, savings are a good thing—and certainly not something worthy of such a meager limit.

“More draconian every year”

To help me understand why we have such an irrational system, I talked to Ari Ne'eman, a visiting scholar at Brandeis’s Lurie Institute for Disability Policy.

That $2,000 limit is not indexed for inflation and has not been updated since 1989. This means its value has eroded greatly over time.

"We've been effectively making it more draconian every year for decades,” Ne’eman said. In the last twelve months alone, the real value of the resources cap has eroded by eight percent, measured by the CPI.

The cap has exceptions that might allow disabled people to build wealth. But they tend to be almost impossible to use. One way that you can hold more than $2,000 in assets, for example, is to create a Plan to Achieve Self Support, and set money aside to accomplish that plan. But in order to get approved, you have to fill out an SSA-545-BK, a twelve-page form that demands a ton of numerical details.

Ne’eman told me something shocking, so much so that I had to look it up for myself. “Approximately nobody uses it. Only a few hundred people.”

He cited SSA’s annual report on the SSI program. And there, in Table V.E3, I found it: 401 people. According to Ne’eman, so few people use some SSA programs that the users actually have to help educate SSA employees on the obscure rules.

"SSA must have a secret plan for disability employment,” he jokes. “It's making all disabled people into accountants, because you have to be one to follow these rules."

A somewhat more usable escape hatch came in 2014, with the Achieving a Better Life Experience (ABLE) Act. An ABLE account has an effective limit of $100,000. But it is limited to qualified disability expenses, which is a fairly broad but not universal category. So to manage life as a disabled SSI recipient, you might need to carefully separate out your different types of spending between your ABLE account and your ordinary checking account—which still can’t get above $2,000.

So why did we not lift the resources cap rather than create an entirely separate type of account?

The first clue is the budgetary score of the bill. ABLE costs a slender $2 billion, and was offset by politically-acceptable savings like reducing Medicare coverage of vacuum pump treatments for erectile dysfunction. It seems the deficit-neutral politics of the 2010s limited how much relief the bill could provide.

The second clue is in how many people have opened ABLE accounts to date: about 75,000 people, according to SSA, or less than one percent of those eligible. Increasing the resources limit would apply to everyone, while the ABLE account—a more complex system you have to opt into—is used by fewer people. Congress’s budget analysts predicted, correctly, that the ABLE accounts would cost less than lifting the resources limit because few people would use them. So ABLE got a few people a much higher asset limit, but at the expense of usability.

Ne’eman, who served on the National Council on Disability at the time the bill was passed, explained why the legislation went in this direction. "A major portion of the political constituency that got ABLE accounts across the finish line was families who wanted to transfer assets to their disabled children but avoid losing [the children’s] Medicaid.” In the absence of an ABLE account, such transfers would exceed the resource limit. He acknowledged that families providing for their disabled relatives is a highly worthy goal, and he didn’t begrudge it in the least—but the harsh budget math of the bill meant ABLE accounts came at the expense of a needed administrative fix to the resource limit for everyone. “I'm still frustrated about it.“

Eight years later, the Brown-Portman bill has no offsets. You can take that as a sign of Portman’s conviction; he’s known for a staid, frugal approach to public finance. Ironically, offsets would probably be a better idea now than they were in 2014, but make no mistake about it: this is the right thing to do, and it’s a good policy, regardless of how it is offset.

$85 a month, and a 50% marginal “tax” rate

Sherrod Brown’s point about the asset limit—that it punishes you for doing the responsible thing—is compelling from a right-of-center perspective, even though it comes from a senator known for left-wing economic views. It actually sounds a lot like a right-of-center argument about taxes.

While SSI and its asset cap are obviously not taxes—the government is paying out money, not taking it in—there’s a similar property to many tax systems: as you make more money and become more self-sufficient, you lose some of those gains to government policy. If you squint and look at it closely, the asset limit is a bit like a wealth tax that kicks in at an insanely low minimum.

Of course, to some extent, policy has to work this way: you can’t raise money from people who don’t have it, and benefits are too expensive for the government unless they either means-test them (limit eligibility to the needy) or raise taxes. And either of these has the “punishment for doing the right thing” property.

But SSI does this in an egregiously inefficient way. The loss of SSI is a fairly hefty penalty, and the loss of Medicaid is potentially much larger. Both can be triggered, all at once, by going a dollar above the $2,000 limit. This is an inefficient design, what welfare scholars call a “cliff.”

SSI also has an income-based phaseout. Effectively, for every dollar you earn above a threshold, you lose 50 cents in benefits.

But shockingly, that threshold is just $85 per month. So it’s like a 50 percent “tax” rate with a $85 per month standard deduction.

This phaseout, at least, doesn’t have a “cliff.” But it’s too high of a marginal rate; elsewhere in our tax and transfer system, rates are typically lower than that. And the cumulative rate might be even higher after other means-tested policies are considered.

And the threshold for it (SSA calls it “income disregards”) is so astonishingly low that I asked Ne’eman about it. He believes the number is a holdover from at least 1972, when SSI was created. SSI borrowed some of its numbers from a previous aid program for the blind, and didn’t index them for inflation. Fifty years later, they remain the same, despite a sevenfold increase in the consumer price index.

While work incentives for SSI recipients likely aren’t a major factor in GDP growth from a purely financial perspective, work also helps promote a sense of self-sufficiency and social inclusion, which might be especially important for the disabled.

So the Brown-Portman bill is really just the start of the needed reforms to SSI. It’s the most obvious improvement, but far from the only one. I’d remove the asset cap completely and make the income phaseout more gradual. Ne’eman suggests more simplicity and clarity around Medicaid eligibility as well.

It’s understandable that policymakers didn’t want SSI to be a universal income. Most people who can work for their money should do so, and fiscal space is limited. But in their zeal to restrict SSI to the truly needy—and in their inattention to the program—they have created a bizarre incentive structure and a lot of complexity we don’t need.

"The complexity is what kills us here,” Ne’eman said. “and given the populations this is intended to serve, it's the exact wrong place for complexity."