Don’t play the frontload gambit

Overloading the early years of the Build Back Better plan with extra spending will backfire.

President Joe Biden this week met with both progressive and moderate Democrats in Congress to discuss the contents of the fiscal policy plan, Politico reports. Politico also shares some of the details, which are worrying.

Reportedly, Democrats are planning on allowing at least four of their policies to expire after one to three years, instead of establishing them permanently. The expansions to the child tax credit, the Affordable Care Act, Medicare, and Medicaid will all be temporary.

Taken at face value, this is an awful idea; setting up a bunch of programs quickly only to dismantle them is inefficient. But if you read between the lines, understand the political strategy, and examine the economic context—you find it’s still an awful idea.

The Congressional Progressive Caucus released a statement on the negotiations, which helps explain who is advocating temporary policy and why. “We also appreciate the President fighting for progress on all of these key priorities, even if it is for a shorter period of time, as the CPC had articulated weeks ago is our preferred option to bring down the overall price tag.”

Part of the logic here is text, and part of it is subtext. On the surface level, it’s about budget space: there is an aggregate limit for spending the bill can add over the next ten years, and that limit is the combined amount of tax increases and borrowing that moderates like Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV) are willing to accept. The exact number is up for debate, but it is thought to be between $1 trillion and $2 trillion.

So given this hard constraint, progressives who had hoped for more spending are faced with tough choices. Rather than forgo any priorities completely, or reduce their scope, progressives instead hope to fit their priorities inside the constraints by reducing their duration.

The subtext is that progressives neither want nor expect the programs to expire. They hope that when the benefits are about to expire, they will prove popular and get renewed instead, resulting in a higher overall level of spending.

I’ll call this theory the frontload gambit, and it is sometimes defensible. However, under the particular facts and circumstances of 2021, it is likely to backfire, and both Democrats and the country as a whole would be better served by abandoning it.

It’s a good trick, but not this time

This is a well-worn strategy to wriggle out of fiscal policy targets, and it works much of the time. It is difficult to take away provisions people have grown attached to. Republican attempts to repeal the Affordable Care Act famously failed with John McCain’s thumbs-down vote. Much smaller benefits—even silly-sounding ones like the accelerated depreciation schedule for race horses—can survive through a series of temporary extensions, hitch-hiking year-by-year on other bills. Most recently, it survived by hitching a ride on the December 2020 COVID-19 relief package.

So at least based on historical experience, the progressives’ idea makes sense, from their perspective: expand spending as much as possible, and then count on future Congresses to feel obliged to renew the policies.

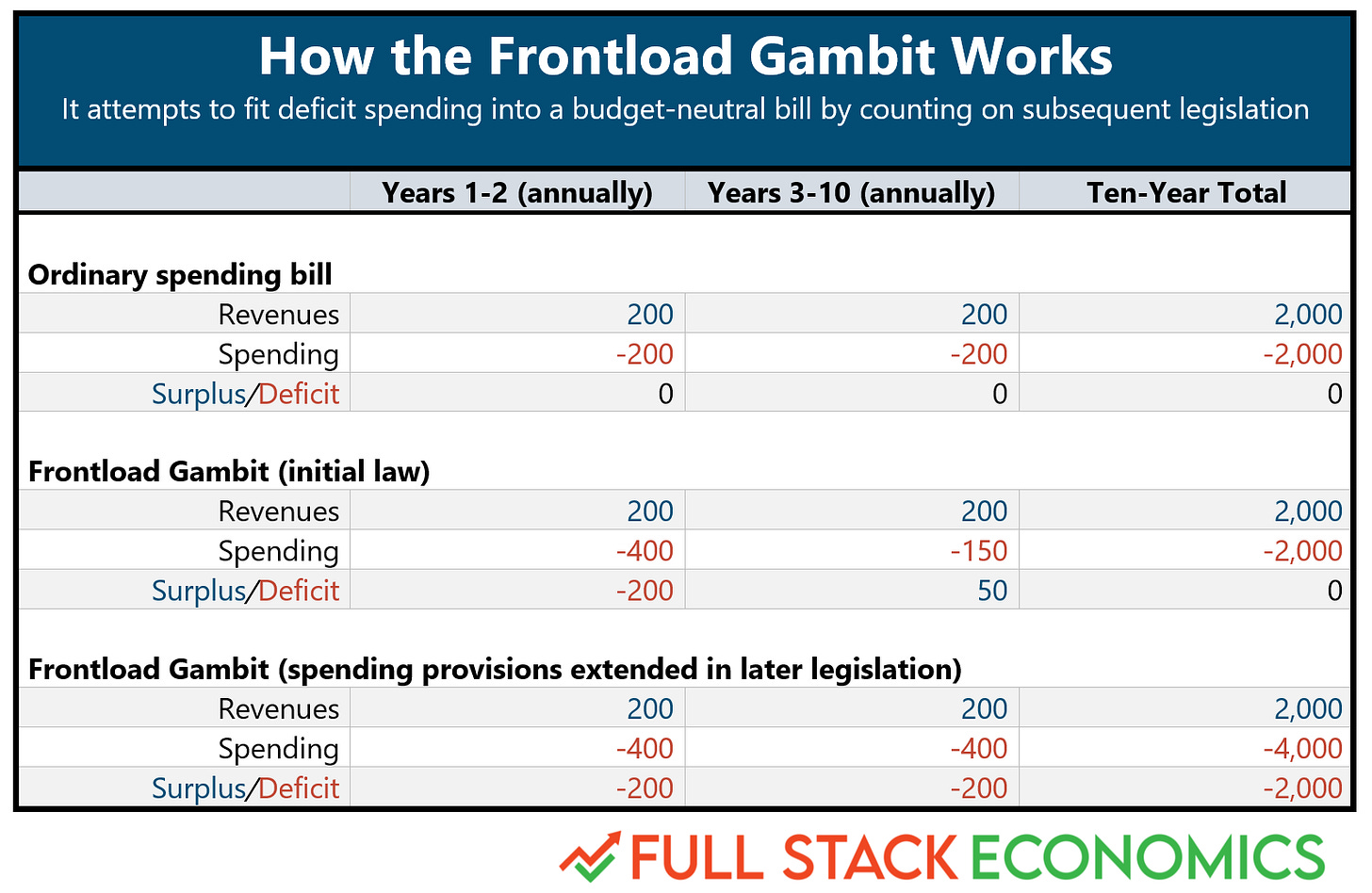

Note that this strategy is about stealthily doing deficit spending, perhaps permanently. For example, say your negotiating partners want a $2 trillion “fully-paid-for” bill over ten years. Under normal circumstances, this might mean $200 billion in new spending, and $200 billion in new revenues, each year.

But under the frontloading strategy espoused by the progressives, you might keep the revenue plan the same—take whatever $200 billion in tax hikes you can get each year—but unleash a flurry of programs early. You might have, say, $400 billion in spending in each of the first two years, and $150 billion in each of the next eight. You still total $2 trillion, but you get more of it up-front. And if you get to extend the programs, you eventually end up with $400 billion in spending every year, and what was initially a $2 trillion fully-paid-for bill becomes a $4 trillion half-paid-for bill.

The nature of gambits, in politics as in chess, is that they are risky, potentially unsound plays. And here, with the high-pressure, high-inflation economy already brought about by prior COVID relief packages, the risks are substantially more to the downside. The Congressional Progressive Caucus is pushing Biden towards a structural blunder at the macroeconomic level—and likely, the political level.

Upsetting the great balance of money and stuff

In most transactions in a modern economy, one person has money, and the other person has something of real value, like a finished good, or labor, or a house.

For a long time—most of the 2010s—people with money seemed to have an advantage over people with stuff. If you had a job for someone to do, it would be easy to find many willing workers. If you had the money to buy a product, it would generally be easy to get it shipped to you quickly.

This explains why deficit spending worked out so well in the 2010s. Federal deficits would release more money into the rest of the economy. That money would result in new spending, and firms would simply hire new and willing workers at prevailing wages in order to help fill the new orders. When it came time to renew the deficit-creating federal policies, it seemed perfectly defensible, because there weren’t obvious ill effects to speak of.

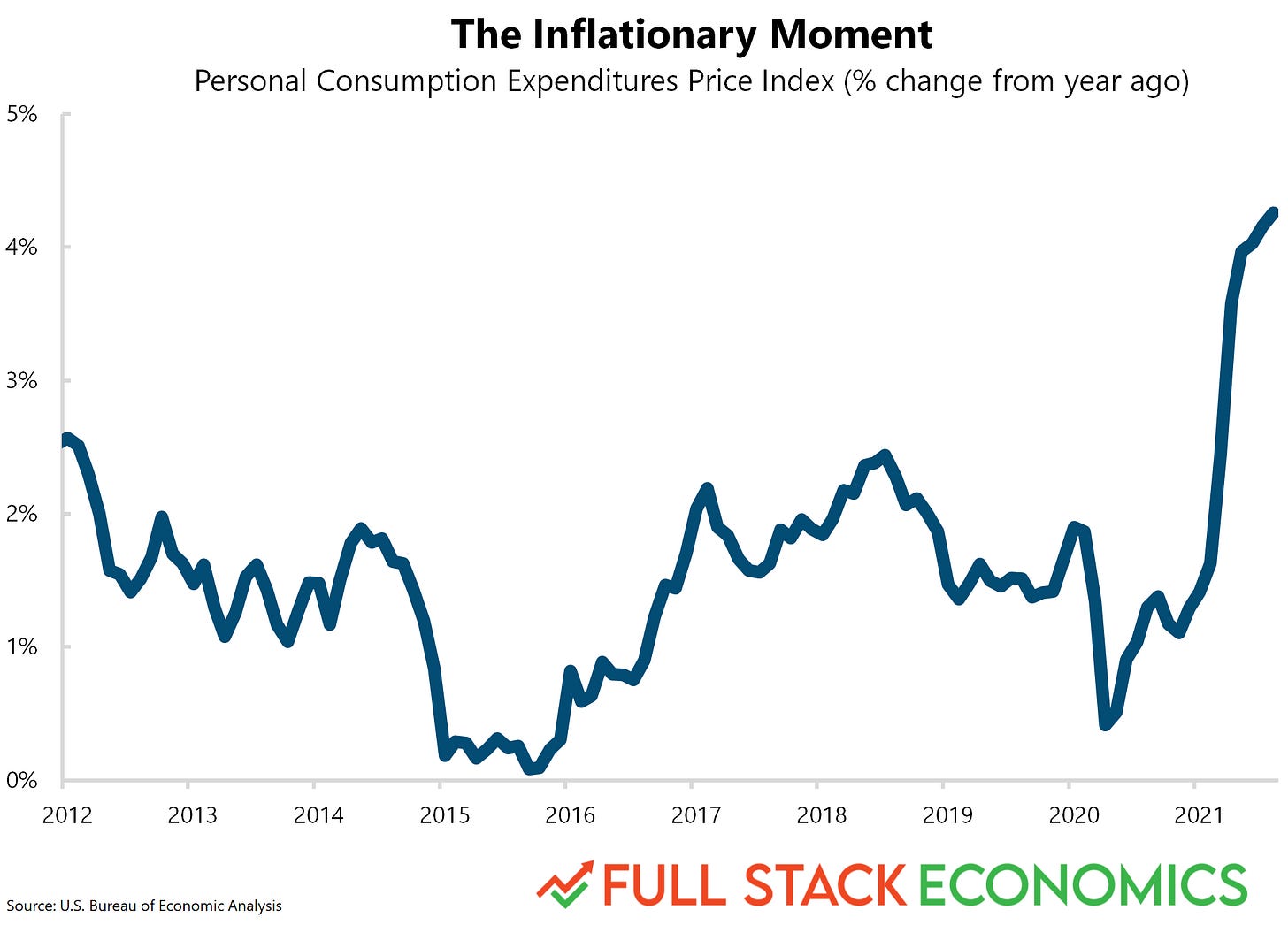

By contrast, in 2021, people with stuff—homeowners, workers, merchants—seem to have the upper hand in transactions. Cash seems plentiful, especially after several previous fiscal relief efforts. Real goods and services are scarce at current prices, and inflation is rising. Additional deficit spending in 2021 could upset the balance even further, releasing even more money into the economy and driving inflation higher.

This gives pause even to dovish economists who are normally sanguine about inflation and deficits. Bloomberg’s Karl Smith, who ruffles a lot of feathers with provocative opinion columns like “America Needs Higher, Longer-Lasting Inflation,” is wary of a frontloaded bill. “I think it would add to aggregate demand,” he tells me. “I'd be cautious about doing that at this point.”

Smith outlines two scenarios; one in which stimulus-driven inflation forces the Federal Reserve to raise interest rates, curbing private investment somewhat, and a more extreme one in which the Federal Reserve cannot get inflation under control without resorting to more extreme hikes, inducing a recession.

He thinks the more modest scenario—in which inflation spurs an earlier-than-expected Federal Reserve hike—is the more likely one. But it is notable that even the dovish Smith is beginning to sound more hawkish in the near term.

Driving the economy beyond its capacity might be undesirable in itself, but it would also be a political liability for Democrats; critics could draw a connection between inflation in 2021 and the surge of Biden spending programs, and infer that we were better off without those programs.

While it is hard for a policy’s opponents to repeal them directly, it is much easier for opponents to let them expire. And it is easy to imagine a situation where a runaway inflation narrative leads to Democratic losses in the 2022 midterms, and Republicans enter office campaigning on taming inflation and refusing to extend the Biden policies. Rather than cement a large and permanent amount of new spending, the gambit is likely to condemn most of its provisions by making them to blame for inflation.

Getting it backwards

The Biden administration currently presides over a very peculiar situation. In the short run, it has a real economy constrained by COVID-19, but a monetary economy that is flooded with the cash from previous relief efforts, including the bipartisan CARES Act under President Trump, and the Democratic American Rescue Plan under Biden. In other words, the economy is vulnerable to the symptoms of overheating, like high inflation.

We have already begun to experience those symptoms, and that has empowered moderates like Joe Manchin to oppose more spending. But in the longer run, as I’ve noted before, markets actually give Biden—and the U.S in general—low long-run borrowing rates.

There are strong forces that “cool down” economies over the long run. The global population is getting older and richer day by day, and that means more and more wealth needs to be saved for retirement. Once stimulus money finds its way into the hands of patient global savers, it will slow down, and there will once again be fiscal room.

The bond markets are betting on this; the low ten-year interest rates suggest the U.S. has plenty of space. But the high inflation reads suggest that the U.S. does not have capacity to deliver on a bunch of new promises of real goods and services right this instant.

This suggests that the frontloading approach advocated by the progressives is backwards: the economy needs short-run cooling, but deficits in later years could easily be absorbed by a growing economy.