Cities are threatened by breakdown in public order

Cities depend on the idea that having other people around is good. Is that still true?

In 2019 I purchased a home relatively close to the center of Washington D.C. I thought at the time it would be an excellent investment, and likely to appreciate faster than many other houses. Homes situated near the center of big job markets had fared well during the 2010s, and I expected most of those trends to continue.

Today the future of my investment seems murkier. By all means, 2019 was a great time to buy a home. The COVID-19 pandemic made us stay home more, increasing demand for housing, and the high-pressure economy built by the COVID-19 relief bills rewarded those with aggressive balance sheets, like new homebuyers.

But I might have gotten the location wrong. Commute distance became less of a factor as more employers turned to remote work. This made suburbs and exurbs relatively more advantageous than before; they still offered more ample square footage, and without the drawback of hellish morning commutes they had become a better deal.

But there’s more than the remote work story here. I also see hints of something much more threatening. Several features of cities in the 2000s and 2010s that made them so pleasant seem to be threatened. After a long decline, crime is increasing again. Public transit networks are more dangerous and less reliable. And a bout of dangerous driving has dramatically worsened pedestrian safety.

The core proposition of cities is that other people around you provide more benefits than harms. That was certainly true in 2019, when I bought my home. I think it’s less true now.

Neighbors are usually good for you

Having other people around makes your economic life better. You might object to this. Maybe you find other people annoying. But it’s likely that you live in a neighborhood with other people around. Perhaps even lots of people. And it’s worth thinking about why you chose to live near other people, even though you could get more house for your dollar if you lived in a remote rural area.

Living near other people confers indirect benefits that are hard to pass up. People open businesses or offices that you might like to work at, giving you a wider menu of choices as a worker. And they also help patronize shops or services that you might use from time to time, giving you a wider menu of choices as a consumer.

Could you get these things without your neighbors? Usually not. Employers need employees. Stores need customers. In general, the things you like about your neighborhood don’t exist despite your neighbors, they exist because of your neighbors.

In The Truman Show, Truman Burbank (Jim Carrey) discovers that his home, Seahaven Island, is an artificial world built for a television show. Businesses and offices are fake. People only work in them or patronize them when he’s there to see. This let Seahaven sustain many storefronts despite a limited number of actors to populate them. But real life doesn’t work that way. You need people—real people—keeping the lights on in these establishments, even if you visit only a few times a year.

At times these benefits can be pretty large. I have several grocery stores within a ten minute walk from my home. If I need professional help with some issue like HVAC or garage door repair, I have a competitive market with many vendors to choose from. And even some very niche hobbies and cuisines are readily catered to. This all makes a dense, central location a better buy.

Crime makes cities a worse proposition

Unfortunately, crime turns this all on its head. The more that crime is a problem, the more you start to think of close proximity to other people as a negative, rather than a positive.

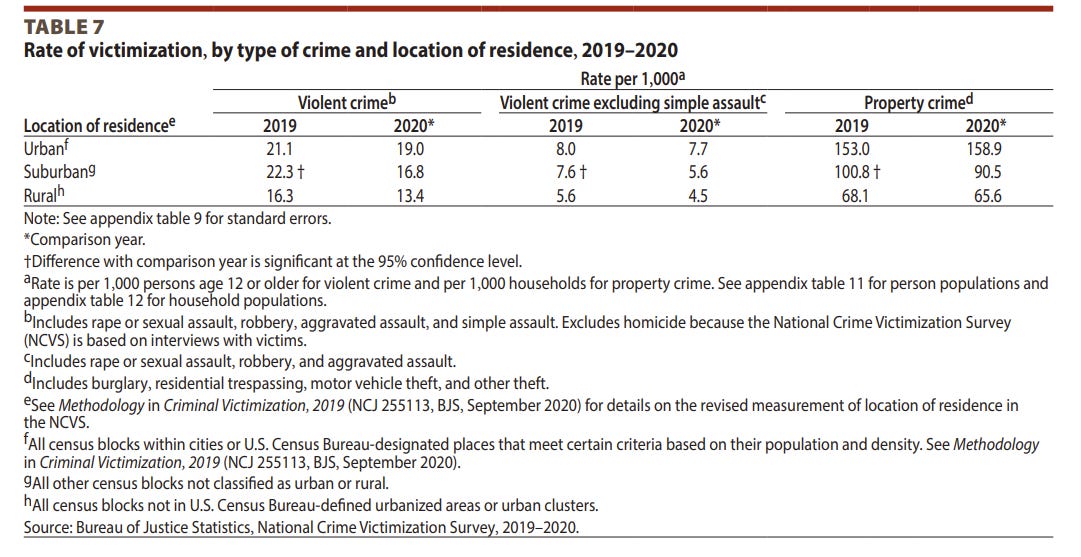

When it comes to crime, cities just have it worse. For example, consider these survey results from a report by the Department of Justice. For a variety of different definitions of “crime,” the ordering is largely the same: it’s most prevalent in urban areas, followed by suburban areas, followed by rural areas.

One reason is opportunity: It is easier for thieves to take things when they have more targets to choose from. It is easier to approach or threaten people when they are on foot rather than in a vehicle. And it is easier for criminals to avoid notice in a place where strangers are seen relatively frequently.

So when crime is high in general, denser areas tend to be especially dangerous. Not only because you have more potential criminals near you, but also because a denser population can make your area more attractive to ruffians.

And crime is becoming a bigger problem.

It’s hard to describe this phenomenon with precision or certainty. The national data for crime is horrendous patchwork collected from a variety of smaller government authorities. The FBI is in the process of transitioning to a new reporting system, but that system is likely to have problems of its own, especially in its first years. Much crime goes unaccounted for, either because people don’t report it to the police, or because it doesn’t make it from local authorities to national metrics.

But we do know some things for sure. Worries about crime are certainly on the rise, and at least some important crimes, like murder, have definitely increased. Because of its importance, murder is the most likely to have a complete accounting. And the numbers aren’t good. Per CDC data, the nationwide rate has gone up about a third, from about 6 per 100,000 prior to the pandemic to about 8 per 100,000 today.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, even as murder rates rose, the measured rates of many lesser crimes declined. This led some commentators, like The Atlantic’s David Graham, to declare that America was having a violence wave, not an overall crime wave.

Even as stated, this is not necessarily an encouraging development (violence is important!). But the apparent drop in property crimes may not last. There are many unusual circumstances: more people were at home, providing fewer opportunities for muggers or burglars. And it’s likely that the pandemic and the George Floyd-related protests of 2020 distracted from complete record keeping.

I think it’s most likely that non-violent crime—or at least, the propensity to commit non-violent crime where possible—is also on the rise. Auto theft, another crime that—like murder—is hard to miss, is up 16.5% in 2021 relative to 2019, according to insurance industry groups. And our friend Matt Yglesias notes this is part of a greater pattern: many different kinds of bad behavior are on the rise, from reckless driving to drug overdoses to “unruly passenger” incidents.

Overall, other people have become worse to be around, relative to how things were in 2019. This recent rise in bad behavior doesn’t undo all of the substantial progress made in fighting crime—for example, the murder rate used to be as high as 10 per 100,000 three decades ago—but it does undo some of that progress.

It is not quite clear how to apportion blame for this trend. Yglesias put together an impressive collection of bad behaviors that took off in 2020. Perhaps the COVID-19 pandemic just made people more antisocial. And as Graham notes, there are a variety of possible causal mechanisms involving the protests of 2020. Some cities elected more lenient prosecutors. (Some voters are now seeking to reverse that.)

But whatever the cause, it’s a substantial risk to the long-term health of cities.

Public transportation needs to get back on its feet

The quality of city life is closely tied to the quality of the public transportation network. The benefits, at least in theory, are substantial. Even if you’re not an environmentalist, it can be nice to go places without needing to drive. And you can save a lot of money by forgoing a car (or sharing a car with a spouse). Trains—and sometimes buses—have dedicated rights of way that can allow them to move faster than highway traffic. Public transportation can also bring in a large number of high-income commuters to offices, increasing commerce and improving the tax base. For these reasons, New York City’s mayor, Eric Adams, has been focused on luring commuters back into the city.

But recently, many transit systems have been plagued by poor maintenance and poor public order. These problems seem to have worsened over the course of the pandemic.

A particularly striking incident last month exemplified both trends at once: a disturbed man committed a mass shooting on the N train in Brooklyn, wounding 29. Miraculously, no one was killed. But broken surveillance cameras hampered the search for the suspect, and he was only caught because he turned himself in.

David Graham connected the incident to a larger “subway-crime death spiral,” where “fear of crime begets low ridership, which in turn begets more crime.” Higher ridership brings in more fares, which can help with safety improvements. And perhaps even more importantly, the presence of more law-abiding citizens on public transportation can help dissuade the most egregious crimes with a sort of “safety in numbers.”

Commuters definitely see crime as a big issue. A poll by TransitCenter taken prior to the COVID-19 pandemic showed that “safety on bus” and “safety walking to/at stop” were two of the three top priorities for bus riders, even those earning less than $35,000 a year. (The main purpose of the poll was to push back against the idea of offering fare-free transit. Even lower-income commuters tend to prefer frequency and safety to fare cuts.)

In Graham’s telling, the fear of crime on transit is overblown, if directionally correct. The MTA recorded just 1 felony per million riders in 2019, and 1.48 per million in 2020, and 1.63 per million in the first few months of 2021. These numbers are low on a per-ride basis, but they’re rising at an alarming rate. Moreover, commuters use public transit hundreds of times a year—and thousands or even tens of thousands of times in a lifetime. And there are plenty of scary incidents that fall short of a felony.

In my hometown of Washington DC, the same general pattern from New York applied: crime steady, or even up, despite fewer riders, meaning more crime per capita. For example, aggravated assaults on public transit rose from from 130 in 2019 to 183 in 2021, even though daily rail ridership was down from 626,000 rides per day to 136,000, and daily bus rides were down from about 350,000 to about 140,000.

And mass transit isn’t the only mode of transportation threatened by recent anti-social behavior. As Yglesias mentioned, reckless driving has worsened since 2019. One consequence of this is pedestrian deaths, which are up about 17% from the first half of 2019 to the first half of 2021, according to the Governors’ Highway Safety Association (GHSA.)

Eyes on the Street

The bottom line for cities is that they are dependent on a fair amount of trust. People are often more vulnerable; they spend more time on foot and in public place. And they are dependent on the people around them being more of a benefit than a drawback.

Jane Jacobs, an activist and urbanist, saw other people as a benefit. “When there are people present in a public space such as city streets, it strengthens the space and inspires social cohesion,” she wrote in 1961. She understood that crime could be a problem, but even there—in her most famous passage—her solution was other people. “There must be eyes upon the street, eyes belonging to those we might call the natural proprietors of the street. The buildings on a street equipped to handle strangers and to insure the safety of both residents and strangers, must be oriented to the street.”

Jacobs’ idea, essentially, is that if you have a high enough number of law-abiding citizens around and engaged with public places, they become safer. At a high enough ratio of responsible people to lawbreakers, this works; it was working in our major city centers prior to 2020.

But it’s not working as well now. Fewer law-abiding commuters use transit. Social distancing directives made people engage less with public spaces. And for whatever reason, people in general seem to have become more anti-social. All of this makes it harder for the Jane Jacobs view of the world to prevail.

In the worst case scenario, some of these problems could become self-fulfilling as law-abiding people disengage from public spaces or even move away, making it even more difficult to create the sort of safety in numbers that cities used to enjoy.

I don’t think these issues can singlehandedly destroy a great city like New York or DC. But they’ll make urban living worse for a time. And I wouldn’t be surprised to see them play a role in the decline of cities with fewer advantages.